Dr. Jillian Davidson reports on an international conference focusing on “European-Jewish Literatures and World War I”, held at Graz University, Austria.

Approximately 40 scholars gathered from Austria, Hungary, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Israel and America, June 10th through 12th, in Graz for an innovative International Conference dedicated to “European-Jewish Literatures and World War I.”

For the record, Graz is the second-largest city in Austria and was recognized as a World Cultural Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999. Home to six universities, the oldest being Graz University itself (founded in 1585), 15% of the population of Graz comprises of students. In many ways, Graz therefore seems to be the Boston of Austria, though its twin cities are in fact Montclair (NJ) in America, Coventry in England and St. Petersburg in Russia.

The once thriving Jewish community of Graz, together with its synagogue, was destroyed by the Nazis. The Rabbi of that synagogue, David Herzog had also been a professor at Graz University (1909-1938). In 2000, on the anniversary of the Reichskristallnacht, the city council presented the remaining Jewish community with a new synagogue, as a gesture of remorse and reconciliation.

One random fact about Graz must surely be that its former student, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, lent his name to the term “masochism.”

Also on a lighter note, Arnold Schwarzenegger was born and bred in a farming village 2 km from Graz. For a while, the Graz football stadium bore his name.

This conference was the brainchild of Petra Ernst, a scholar and teacher from the Centrum für Jüdische Studien (Center for Jewish Studies) at the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. She thanked her extensive support team: the University’s Vice-rector for research, Peter Scherrer; the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, Helmut Konrad; the Department of Science and Research of the Province of Styria; the Graz Mayor’s office; the Austrian Science Foundation; the Fritz Thyssen Foundation to advance science and the humanities and her younger colleagues, who include Britta Wedam and Lukas Waltl.

As a result of this concerted effort, Petra Ernst succeeded in turning a gem of an idea into a grand reality. “As far as I know,” she said, “this is the first time that researchers from different disciplines are meeting to discuss European-Jewish literatures in the sign of the Great War, thus emphasizing transnational perspectives in a research field which is dominated by national narratives till today.”

When introducing the conference, Dr. Ernst clearly defined her terms and goals: War Literature in the context of WWI refers to literature which described, commented on and interpreted the manifold expectations, hopes, fears, experiences and memories connected to the First World War. Long, but narrowly, associated with canonized writers, in German literature, these authors have included Erich Maria Remarque (German), Arnold Zweig (German Jew), Ernst Junger (German), August Stramm (German), Ernst Toller (German Jew) and Karl Kraus (Austrian though born Jewish). Since the 1980s, however, the scope of literature has broadened to include non-fictional texts such as newspapers, journals, letters, postcards, songs diaries, memoirs, reports or essays.

Studies of war literature from different nations have shown that war experiences and sufferings in England, France and Germany actually constituted a common and potentially connective experience. Yet, they did not yield a common European history or memory of the war. Even in Germany and Austria, both countries which shared the experience of defeat, different literary reflections on war developed, due to their divergent, historical understandings of nation and state. Germany promoted a unitary idea while Austria maintained a multinational notion/dream.

“Jewish war literature” was a term used by the Austrian-Zionist psychologist and educator, Siegfried Bernfeld as early as 1916. “The War has generated a kind of Jewish war literature, part of which concerned itself with concepts in the Bible, or in Judaism as a whole, War and Peace, while the other dealt with a journalistic discussion of the solution of the difficult problem of Eastern European Jews.” This was an assertion well corroborated throughout the program of the conference.

As Petra Ernst emphasized, Jewish World War One literature has been largely forgotten, and overwritten by the Shoah. Even those literary scholars who have turned their attention to the subject often deal with canonized authors, which, in Austrian literature, has meant Joseph Roth, Fritz Mauthner, Martin Buber or Stefan Zweig.

Petra Ernst contemplated that a comparison of historic sources with literature promised new insights into the contexts of war. Given this heuristic double perspective of literature and history connected by the war “…our conference could be a first step in exploring a neglected field of literature and history, and I do hope others will follow us.”

One example of how literature and history converged at the conference would be the two different approaches to the seminal war diary of the Russian-Jewish writer, ethnographer and humanitarian, S. Ansky. Whereas I contextualized “The Jewish Hurban [destruction] of Poland, Galicia and Bukovina” (1921) within a Jewish literary tradition, Kerstin Armborst-Weihs (Mainz) analyzed Ansky’s record of Jewish Life on the Eastern Front territories within a historical context.

Even though there was no presentation on the postwar boom of Yiddish translations of World War One classics, such as “All Quiet on the Western Front,” Jeffrey Grossman (Charlottesville) spoke about the function of Yiddish translations within German and German Jewish culture during the war.

The most recognized of all Anglo-Jewish war poets, Isaac Rosenberg, was also absent from the Graz program, but Daniel Dornhofer (Frankfurt) presented a paper on Zionism and Racial Anthropology in Anglo-Jewish Literature under the impression of The First World War. His case study was a 1920 memoir by Redcliffe Nathan Salaman, “Palestine Reclaimed; Letters from a Jewish officer.” Salaman, a medical officer in the British Army’s 2nd Judean Battalion in Palestine, later authored “The Influence of the Potato on the Course of Irish History” (1943). In the war, he envisioned in the transformative power of Palestine the potential for a racial return and rebirth of pure, “blue-blooded Ashkenazim.”

Instead of a talk on the more canonized writer, Joseph Roth, Nurit Pagi (Haifa) examined the philosophical, political and literary transformations of Czech-born Max Brod around World War One. According to Pagi, the key to Brod’s “Das grosse Wagnis” (The Big Gamble, 1918) lay in the title of Theodor Storm’s 1876 novel “Culpa patris aquis submersus.” For Brod, the greatest of father figures, the great Emperor Franz Josef, vanished beneath the waters with guilt. For Brod, the Hapsburg Empire had represented the best political multinational empire. In World War One, however, the state stopped caring for its sons and to an extent Judaism was able to return to Brod the father figure he had lost.

Jewish writers of the First World War clearly encompass an enormous geographic expanse, but one presenter was able to visit the town of residence of her writer on her way to the conference. Sandra Goldstein (Vienna) spoke about Gershon Schoffman (1880-1972), a Russian-born, Austrian-based writer, who had lived twenty minutes from Graz, in Wetzeldorf. Goldstein described Schoffman’s life as an integral part of Jewish history, yet he has remained an outsider. He has received less literary attention than, for example, Uri Zvi Greenberg who also wrote in Hebrew and in response to the violence of war, pogroms and anti-Semitism. Greenberg, however, immigrated to Palestine early and enthusiastically in 1923, whereas Schoffman (whose name, Gershon, ironically means lived there) went only when forced and without another option in 1938.

The horrors of World War One coupled with Schoffman’s love affair and marriage to Annie Plank, a 16-year-old Austrian peasant girl from Wetzelsdorf. “The war that had destroyed the order of things — enabled the encounter of two different worlds, that of the Jewish refugee and the Austrian village girl…” Schoffman himself was thirty-five, a lonely man in a foreign city and an estranged war.

Goldstein elaborated how Schoffman used biblical texts and comparisons to write about hunger, prostitution, physical casualties and moral degradation in war. Whereas Pagi focused on the loss of paternal male figures in Brod’s novels, Goldstein concentrated on the fall of female characters in Schoffman’s short stories. The point being that Schoffman felt that there was no escape from the Hell which man has created, no escape from man’s bestiality.

The last speaker of the conference, Ilse Josepha Lazaroms (Budapest/Jena) quoted aptly in the title of her talk from the Jewish literary critic and writer, Aladár Komlós who in 1921 referred to “Jews at the crossroads.” Lazaroms then showed how Komlós and two other Hungarian Jewish writers Erno Szép and Arthur Koestler, at different times responded to the rupture of World War One, and more traumatically perhaps to the Treaty of Trianon (1920) between the Allies and Hungary. As a result of the war and this treaty, a third of Hungarians lived beyond the new borders of Hungary. Despite the traditional patriotism of Hungarian Jews, events that took place shortly after the war, and particularly the political upheaval caused by BéIa Kun and his Jewish supporters, brought about a rise in anti-Semitism. In 1920, Hungary was the first country to instate a numerus clausus (educational quota, the first anti-Jewish law in inter-war Europe), in effect, ushering in the cancellation of emancipation.

It was perhaps most fitting that in a conference which covered Jewish literatures written in so many different languages — Yiddish, Hebrew, German, Hungarian and English — the Keynote speaker addressed the topic of “The Jewish Great War” with reference to the most transnational, translingual of media. As Jay Winter emphasized: language frames memory and different languages, both spoken and visual, present the different facets of war in a variety of ways. For Jews, this is especially pertinent because the question of which Jewish or national language to work in was a real one. In his answer to this self-posed question, Winter deliberately chose the language of photography. “The power of photography to act as a trigger of memory is familiar to us all.”

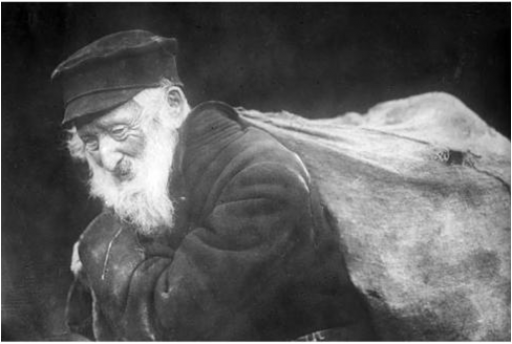

The 980 photos taken by Dr. Bernard Bardach offer a treasure chest of memories for the historian. Dr. Bardach was 48 years old in 1914 when he served as a physician in the Austrian Army on the Eastern Front. He had ties with Graz where he had studied medicine. The photos show the story of a Western-educated Jew encountering the ancient world of Eastern European Jewry, affected by war. Bardach took photos of synagogues, pogroms, cemeteries, Jews hanging, Jews suffering from economic hardships, prostitutes, typhus wards, soldiers at rest, hunting, putting on concerts, graves of Jewish army physicians. Bardach’s Jewish consciousness was evident in his proud choice of Jewish subjects. Through these photographs, “he froze time. He brought memory and history together.” In many ways, he is kin to Ansky, who, while distributing money, food and medicine, was capturing this same world on paper by means of the written word. He is Ansky, but with a lens instead of a pen. He also uncannily reminds us of Roman Vishniac who came later with his camera to record the life of Eastern European Jewry on the eve of the Second World War. Bardach’s photos reveal “a vanished world indeed.”

Jay Winter is fond of saying that, when he went to Columbia University during the Vietnam War, he fell under the sway of the distinguished historian, Fritz Stern, “my first real teacher.” In 1965, he took Stern’s seminar of the First World War, and 48 years later he is still in that seminar. “I haven’t finished yet.” On a personal endnote, twenty odd years ago, this writer sat in a series of lectures in the Seeley history faculty building in Cambridge, given by Jay Winter. His lectures inspired in me the desire to write a doctorate on the First World War in Jewish literature and to a degree, I too am still in that lecture hall.

It certainly felt that way in Graz last week!

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author