Flanders House New York and the Arts in the Armed Forces organised a commemorative event on August 4th 2014. Josef Goodman went to the performance, and has written this report for Centenary News.

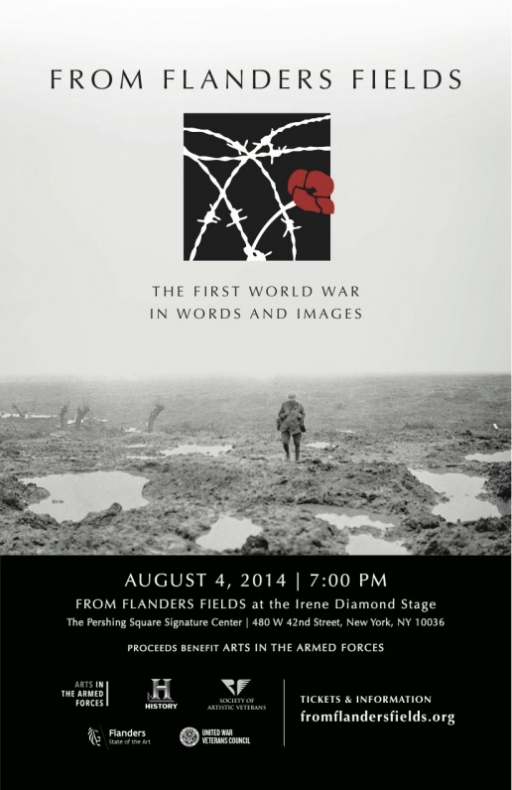

The auditorium at the Irene Diamond Stage of the Pershing Square Signature Center in New York was well filled. Young and old had gathered for the premiere of “From Flanders Fields”, a multimedia performance of readings and images from the Western Front. The date of the event was August 4, 2014, the one-hundredth anniversary of the German invasion of Belgium and the British declaration of war.

At center stage stood two microphone stands. These were flanked by two sections of chairs, on which sat 13 performers: actors, some of whom were war veterans, and others who were historians of American, British, German, French, and Belgium nationalities.

Two organizations, Flanders House New York and the Arts in the Armed Forces, collaborated to produce this performance. The mission of Flanders House New York is to promote a better understanding of the region of Flanders, including its culture, history, government, research, education, and innovation.

The Arts in the Armed Forces, meanwhile, is a non-profit foundation run by the actor Adam Driver, who is perhaps best known for his performance in HBO’s Girls. As the AITAF announces on the mission page of its website, the group “bridges the cultural gap between the United States Armed Forces and the performing arts communities by producing theatrical and musical performances for mixed military and civilian audiences.”

The partnership between Flanders House and AITAF was, therefore, highly appropriate. Both are outreach and education-driven entities. As outlined in the program, the purpose of this production was to “introduce the broader American public (including young adult audiences) to the history and literature of the entire War (not just the U.S. involvement in 1917/1918).”

Unquestionably, “From Flanders Fields” succeeded in its mission on the night of the 4th. The 90-minute performance was a splendid crash course in the literary and political “Who’s Who” of the Western Front.

Dozens of poets, novelists, memoirists, and politicians had their words read aloud before an audience of two hundred, gripped by the moment, the diction, and the quality of the production. The ghosts brought back to life included many of WW1’s literary giants – Kipling, Brooks, Owen, Sassoon – and lesser known characters such as Mary Borden and Jessie Pope.

Among the most memorable performances from the night was Alan Seeger’s “I Have a Rendezvous with Death.” In this poem, the young New York native Seeger marks the contrast between the life that Spring brings into the world and inevitable death awaiting the poet by the barricades. “I shall not fail that rendezvous,” Seeger promised. And live up to that promise he cetianly did. On July 4, 1916, while serving in the French Foreign Legion, the 28 year-old died at the Somme.

The performance of Mary Borden’s “The Song of the Mud” left a similarly haunting impression. Born into a wealthy Chicago family, Borden was living in England at the outbreak of the war. She invested her own money to equip and staff a field hospital close to the Front, where she served for three years.

In her poem, Borden draws upon her experience with the most salient feature of the war zone’s landscape. The first stanza reads:

This is the song of the mud.

The pale yellow glistening mud that covers the naked hills like satin,

The grey gleaming silvery mud that is spread like enamel over the valleys,

The frothing, squirting, spurting liquid mud that gurgles along the road-beds,

The thick elastic mud that is kneaded and pounded and squeezed under the hoofs of horses.

The invincible, inexhaustible mud of the War Zone.

Borden’s words travel across the century to remind the audience that it wasn’t only men like Seeger, but female participants too, who were affected by the war.

“From Flanders Fields” also reminded the audience that poets and novelists were not the only authors of war literature. The political actors of the day bequeathed a genre of literature that deserves commemoration equal to others. Actors read aloud from the memoirs of Paul von Hindenburg, Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and the November 11th Armistice announcement.

And all the while, one could not forget that many of these actors were veterans – veterans of wars far removed in time and space from the Western Front of 1914-1918. The War to End All Wars had failed to live up to its eponymous promise, as these men and women returning from the deserts of Iraq and steppes of Afghanistan testified. Indeed, who could speak with more authority on the subject of war than these veterans?

Flanders House and AITAF have done a real service in reminding us of war’s enduring tragedy. The somberness of the occasion, however, was mitigated by one fact; that even from the muddy depths of despair and destruction, beauty, genius, and the human spirit, as encapsulated by the spoken words of the evening, also endures and inspires.