Joseph Delves writes for Centenary News about a new art exhibition in London which focuses on George Grosz’s work on Berlin and the First World War.

A new exhibition at the Richard Nagy Galley in Bond Street, London, shows how the Great War impacted both Berlin society and the life of its greatest chronicler: George Grosz.

In the early twentieth century, Berlin was the world’s most self-consciously modern city.

Having become the capital of the German Empire in 1871, Berliners obsessed over creating a ‘Weltstadt’ or World City to rival the established capitals of Old Europe and the new industrialised cities of America.

George Grosz documented Berlin’s tumult of metropolitan modernity; his frenetic cityscapes bustled with caricatures of city types: bloated industrialists, vampish prostitutes, lecherous shopkeepers and pompous generals.

‘Down with Leibneicht’, 1918. Private Collection. Courtesy of Richard Nagy Ltd., London.

Always drawn to the lurid, his work was a biting satire on the hypocrisy of bourgeois society. As war in Europe approached, he documented the fevered enthusiasm of great swathes of the German public for the conflict.

Despite his opposition to the war Grosz volunteered in November 1914 to avoid conscription:

“What is there to say about the First World War in which I was an infantry solider? Of a war that I never liked from the start and with which I never identified? War meant horror, mutilation, annihilation. Did not many wise people feel the same way? Of course there was some sort of mass enthusiasm in the beginning. And it was real. But the intoxication soon blew over, and what was left was great emptiness”.

Deployed to the front he was almost instantly hospitalised with a serious sinus infection, probably brought about by extreme anxiety.

Unfit to serve

Having spent most of February in a military hospital he was discharged as unfit to serve in May 1915. The following period was spent in limbo.

Grosz returned to Berlin but lived in constant fear of being recalled to the front. During this period he produced a prodigious amount of work.

“I drew drunks, men vomiting, men cursing the moon with clenched fists, a murderer sitting on a packing case with the murdered woman’s body inside. I drew wine drinkers, beer drinkers, gin drinkers, and a worried man washing blood off his hands… I drew lonely little men running crazily through empty streets in flight from unknown horrors”.

Upon being recalled in January 1917, Grosz was instantly transferred to a military hospital where he stayed until April when, having suffered a mental breakdown, he attacked a medical sergeant and was subsequently discharged as ‘persistently unfit for war’.

Always at odds with the militarism of German society, Grosz’s experience of war turned him into a life long communist. In 1919 he would be arrested for participating in the Spartacist revolt: part of the great political upheaval that threatened post war German democracy.

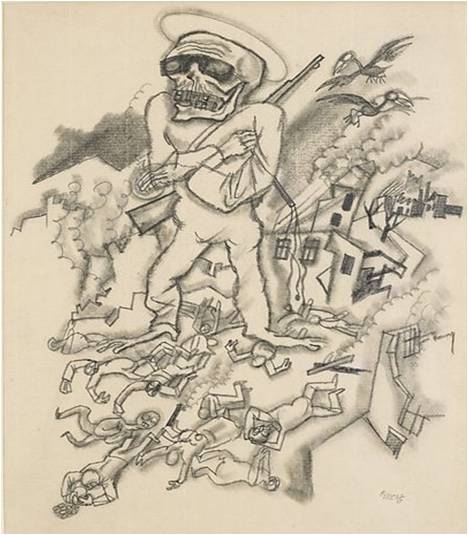

Death returns from the trenches. ‘Grandfather Death’, 1916. Private Collection. Courtesy of Richard Nagy Ltd., London.

Grosz’s lurid depictions of the Berlin street had always suggested a bestiality lurking below a veneer of respectability. German society’s enthusiasm for the war exemplified this hidden propensity towards violence.

Through his depictions of crime and murder in the city Grosz sought to reveal this dual nature.

Although a committed communist he differed from many of his contemporaries in ascribing blame for the war to the whole of German society, not only the generals and industrialists.

War clamour

His paintings from the pre-war period show the masses clamouring for war, seemingly driven to the point of frenzy.

While he largely escaped the horrors of trench warfare his pre-existing misanthropy was heightened by what he saw as society’s unthinking enthusiasm for war, confirming his existing cultural and social pessimism.

From the period immediately before the war onwards his drawings of the city street take on a hysterical quality.

It is as if the chaos of war, which he sees as the expression of society’s true animal nature is reflected back into the city.

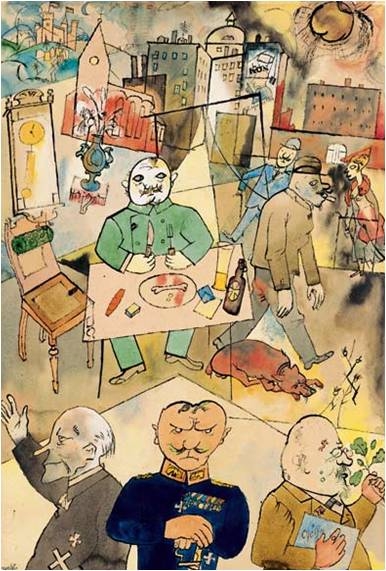

Death appears in the coffee house. ‘Regulars’, 1915. Private Collection. Courtesy of Richard Nagy Ltd., London.

Grosz shows us with a nightmare vision of Berlin during the war.

Completed as his mental state deteriorated during his second period in a military hospital we see into the windows of the metropolis and witness a society tearing itself apart in scenes of sex, murder, suicide and alcoholism.

Death appears in almost every painting in the figure of the skull faced solider returning from the front, not that his appearance seems to give much pause to anyone.

‘Germany, A Winters Tale’, 1918. Private Collection. Courtesy of Richard Nagy Ltd., London.

The apparently insatiable appetites of the industrialist and generals shown eating, drinking and carousing before the war take a darker meaning as the first maimed soldiers return from the front.

Pig carcasses, human limbs belonging to the crippled soldiers and the dismembered bodies of murdered women become muddled, the disembodied parts hidden like jigsaw pieces within Grosz’s intricate paintings.

A butcher, the image of the notorious child killer Fritz Haarmann stalks the streets, carrying sausages of dubious origin, and still those whose fortunes the war has left intact gorge themselves.

Wounded soldiers

In one drawing wounded soldiers with mutilated bodies beg crumbs from the table of a bloated industrialist depicted Moloch like (a recurring image in Grosz’s work), his table set with spoils from the same war that had crippled them.

Always fascinated by the animalistic side of city life, Grosz’s experience of the war served to harden his attitudes towards society.

Cruelty and horror invade his previous joyfully prurient depictions of the metropolis, mirroring the divisive effect of the Great War on German society in the tumultuous decades that would follow.

His experience of the war, both at the front and in Berlin would come to dominate his life and work in much the same way that they would dominate and poison German political and social life throughout the Weimar era.

George Grosz; Berlin. Prostitutes, Politicians, Profiteers runs until 2nd November at the Richard Nagy Gallery, 22 Old Bond Street W1S 4PY London; www.RichardNagy.com.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author