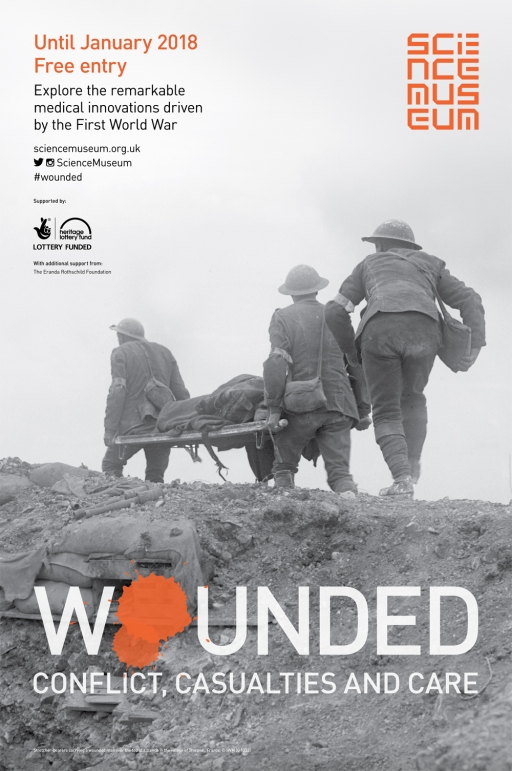

A new exhibition marking the Somme Centenary at London’s Science Museum considers the medical challenges posed by the advent of industrialised warfare in 1914-18. CN Editor Peter Alhadeff went to see it.

Casualty figures have been among most quoted statistics of the 2016 Battle of the Somme commemorations. But this inevitably raises questions – how did medics cope with wounding on an unprecedented scale not only at the Somme, but also throughout the First World War. And for the soldiers who survived, what were their prospects?

This special exhibition does much to provide the answers. An array of objects drawn from the Science Museum’s own collections, and those of other institutions, considers the British experience of treating men blasted by shell fragments, hit by machine-gun fire, or poisoned with gas.

It’s a complex story, not ‘simply a case of progressive innovation triumphing in the face of adversity,’ says co-curator Stewart Emmens.

“Big mistakes were made. Given the scale of this medical emergency, the systems set up to deal with the wounded, both on the front and at home, were often overwhelmed.

“But new medical techniques and strategies did emerge while others were rediscovered, adapted, and evolved through experience.”

And it’s the exhibition’s detail that fascinates.

A WW1 blood transfusion kit (Photo © Science Museum)

A WW1 blood transfusion kit (Photo © Science Museum)

The Great War spurred major advances in the use of X-rays and blood transfusions, for example. Then as now, stemming blood loss was vital to saving life on the battlefield.

As demand for dressings grew, sphagnum moss provided a traditional alternative. Sphagnum dressings, mass-produced from 1915, were naturally antiseptic and highly absorbent. Women and children went into the bogs to collect the moss. They also rolled bandages for the front line.

German sticky tape was considered far superior for binding dressings to wounds, we learn, and it was ‘eagerly commandeered’ by British medics.

X-rays were crucial for locating debris deep inside wounds, and the machinery became increasingly portable, helping to establish the technology as a versatile tool of military medicine.

The exhibition also ventures beyond the battlefields and military hospitals – examining the ‘forgotten story’ of the many wounded soldiers who survived, but were left disabled, disfigured or traumatised by their experiences.

By the end of 1918, more than 30,000 war pensions had been awarded for shell shock, a figure that rose dramatically in the years to come.

A 1917 medical certificate lists the symptoms of the war poet Wilfred Owen after he was blown up in a shell explosion: “He was observed to be shaky and tremulous, and his conduct and manner were pecular (sic) and his memory was confused….he seems to be of a highly strung temperament.”

Displays highlighting advances in X-ray technology and use of antiseptics (Photo: Centenary News)

The post-war period saw gradual improvements in specialist forms of care and rehabilitation. But treatment and attitudes towards mental injury varied greatly. Many returning soldiers were reluctant to seek outside help or depended on charitable support.

“Those who were wounded often felt forgotten, particularly once peace returned. Disabled veterans weren’t even invited to participate in the Victory Parade in London in 1919,” explains co-curator Stewart Emmens.

“Despite the vast numbers wounded in the war and the vast medical machine that was established to deal with them, this is something of a forgotten sorry. We hope this new exhibition may go some way in rectifying that.”

‘Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care’ opened at the Science Museum in South Kensington, London, on June 29th 2016. It runs until January 2018. Admission is free.

The exhibition team has worked closely with two UK charities formed during the First World War, Combat Stress and Blind Veterans UK, to share the personal experiences of soldiers wounded in more recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Images © Science Museum, London & Centenary News (exhibition interior)

Posted by: CN Editor