Author Tim Luard reports on a newly republished book of wartime letters home written by his great-aunt, who served as a nurse on the Western Front.

As a child in the 1950s I used to be taken by my parents on the occasional dutiful visit to tea with my great aunt Kate, by that time already well into her eighties. The conversation in the dark drawing room was as dry as the biscuits and I soon escaped into the garden to play. Small boys have little taste for history. It was only later, long after her death, that I realised what remarkable tales Kate had to tell about her four years treating the injured on the front line in the Great War.

Luckily Kate’s tales were not lost, like those of so many others, since she had written everything down as soon as it happened. All their lives, when they weren’t actually sharing the same roof, Kate Luard and her sisters wrote copiously to each other.

So gripping and powerful did the others find Kate’s daily letters home during the first year of the war that they persuaded her to get them brought to a wider audience. Her Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front caused a sensation when it was published anonymously in 1915, revealing to many for the first time the full horror of what was happening in the trenches.

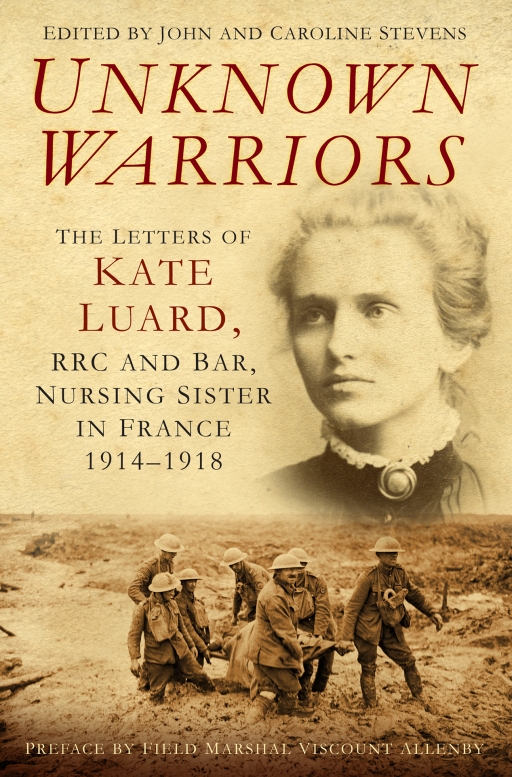

A second book, Unknown Warriors, comprising her letters home for the rest of the war, was brought out by Chatto & Windus in 1930. Both books have long been out of print, but the Diary is now widely available online and Unknown Warriors has been republished by The History Press in August 2014.

Kate Luard in QAIMNSR uniform at Birch Rectory (Photo courtesy of Caroline Stevens)

Katherine Evelyn Luard was born in 1872, the tenth of thirteen children of an Essex vicar. She trained as a professional nurse in the 1890s and served with the British Army in the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Kate was on one of the first troopships to leave for France in August 1914 and for the next four years remained almost continuously in the war zone — as close as a woman could get to the front line — working on ambulance trains, at casualty clearing stations and at various military hospitals in France and Belgium. She soon became a Sister-in-Charge and was one of the few recipients of the Royal Red Cross and bar.

Her letters home provide rare insights into the experiences of both soldiers and nurses, exposing the full horror faced by the war’s wounded as well as the nobility with which so many of them endured suffering and faced death.

In the foreword to the original edition of Unknown Warriors, Field-Marshal Viscount Allenby describes the book as a stirring tale of heroism “unsurpassed in interest by any War novel yet written.”

Until now most of the attention on World War One nurses has been devoted to impressionable young volunteers like Vera Brittain. But Kate Luard, as a war veteran and trained member of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), was one of a select group of hardened professionals.

While others were fainting over the makeshift operating tables, Kate remained indomitable — and, at least while on duty, apparently unshockable. But she poured out her feelings in her letters home, often written in bed before snatching a few hours of sleep.

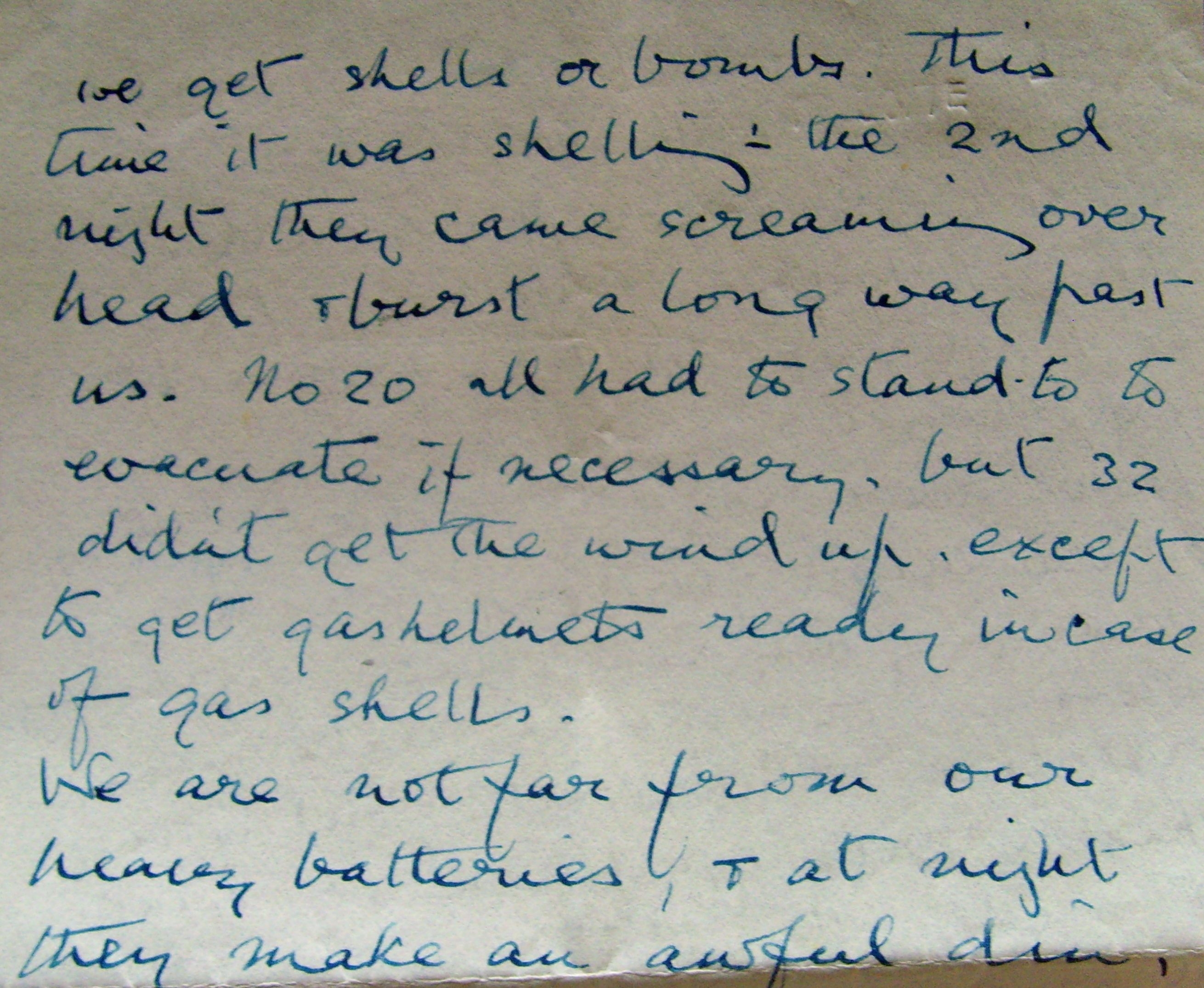

(Essex Record Office / Luard)

She contrasts the ‘pinpricks’ of the Boer Mausers with the ghastly effects of shrapnel and the latest poisonous gases, wonders at the courage and endurance of her latest stretcher-cases and reports word for word her conversations with the dying, who invariably treat her as if she were their mother. After their deaths, she is also the one who has to write to their real mother.

Somehow in the midst of so much grimness — where “men are thick on floors; and floors, men, stretchers all the same colour of trench mud” — she maintains her sense of humour and appreciation of beauty. Even as enemy shells and aircraft fly overhead, she pops out with a colleague to visit a local cathedral or pick violets and cowslips in what’s left of the French countryside.

She puts her experience in her father’s parish to good use by playing the piano at the packed church services that precede major battles. She helps the ‘Tommies’ learn French so they can chat up the local girls on their way to the Front. She even speaks to wounded German prisoners in their own language — and for good measure learns enough Hindustani to help deal with a train full of Indians who think they’re in England.

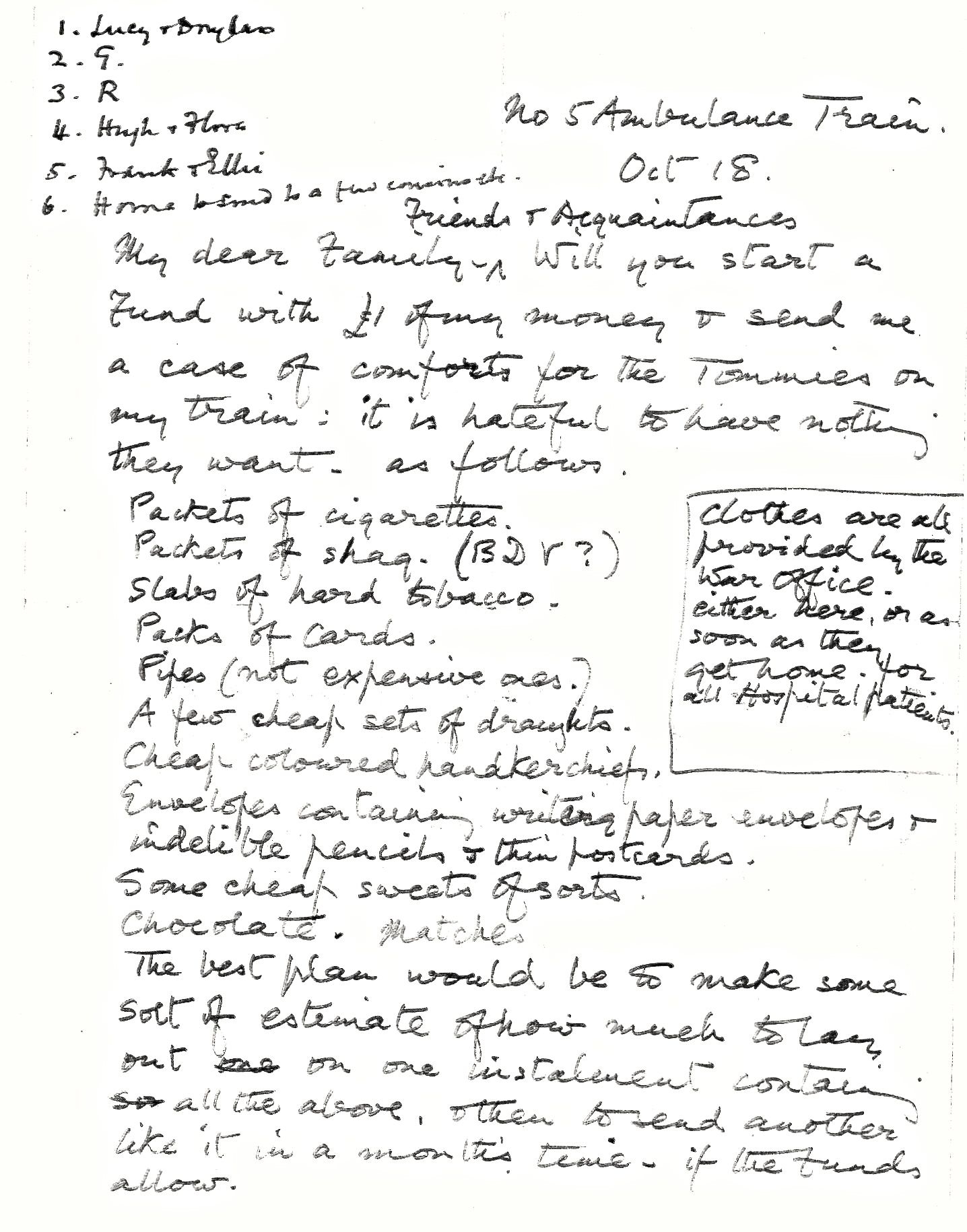

(Essex Record Office / Luard)

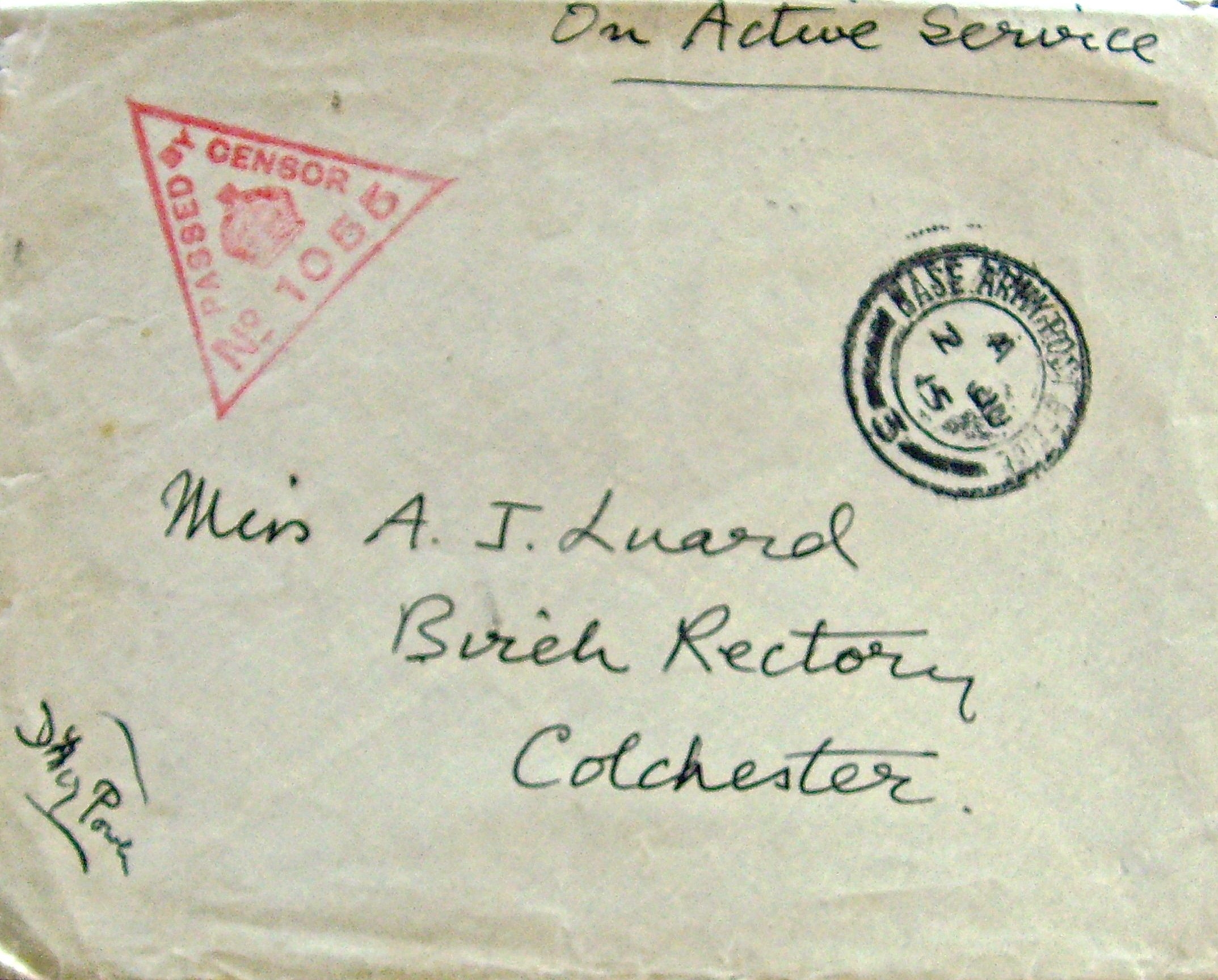

As well as a new introduction and glossary, the updated edition of Unknown Warriors features a postscript containing some of Kate’s more personal, previously unpublished letters, together with replies she received from her family at Birch Rectory, near Colchester. These I found, along with other family papers, among the archives of the Essex Record Office.

The letters she received from home provide a useful counterbalance to her own, more dramatic despatches, painting a vivid picture of life in wartime rural England: of the daily struggle to carry on as normal with everything from haymaking to choir practice at a time when almost every man and boy in the village had gone off to fight.

Kate’s account from the battlefront is an unflinching one, and she expresses growing doubts about the purpose and morality of it all. “In the next war I shall be a conscientious objector”, she declares, “and so will everybody else”.

Yet her sisters continue to proclaim their envy of her privileged position in the thick of it all. “What a thrilling place to be living in”, says one. “How lovely to be able to comfort men in the road straight from the trenches. We’re sending some more tobacco and chocolate for them. We’re all knitting socks now.”

(Essex Record Office / Luard)

The very presence in the war zone of British women came as a great surprise not only to the fighting men but also to the local French citizenry. “We might be freaks from Barnums”, writes Kate. “They can’t make out whether we are a strange sort of English nun or a harem for the British army.”

World War One gave women the chance to stand on their own feet, and Kate Luard was one of the first to do so. Her books are a striking tribute not only to those who fell, but also to those others who like herself did so much to save life behind the lines.

“There is a fine bond”, she writes, “of mutual respect and affection and trust between us and all the men of the Unit, from the CO to the butcher boy, that I’ve never come across before, probably because there’s never been the same combination of work and danger to call it out … and it will always be a bond years hence.”

The proud possessors of such bonds have now passed on. It is no longer possible to hear at first hand of the Great War from someone who was there, and it is too late for the rest of us to show our appreciation to them directly. But the power of personal stories such as my great aunt Kate’s, and of the many others handed down in almost every family in the land, remains as strong as ever.

To discover more about Kate Luard’s writing and nursing in the First World War, click here.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author

Images courtesy of Essex Record Office/Luard Family