The records of more than 8,000 British men who pleaded not to fight in the First World War have been put online by the National Archives in London.

The conscription appeals were heard in the Middlsex Appeal Tribunal between 1916 and 1918 and reveal stories of tragedy, defiance and family hardship caused by the war.

Only five per cent were conscientious objectors. Of the 11,307 separate appeals heard between 1916 and 1918, just 577 were objectors on moral grounds.

The vast majority of the men were appealing for medical, family or business reasons but just 26 received absolute exemption.

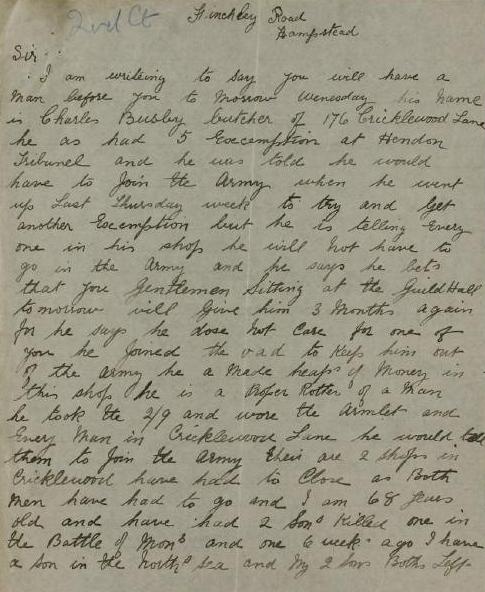

Butcher Charles Rubens Busby claimed he needed to run his shop. But an anonymous letter called him “a rotten shirker” and questioned why he should keep his shop open while “married men have had to shut up their shop and go.”

The letter said: “I am 68 years old and have had two sons killed in the Battle of Mons. He is telling everyone in his shop he will not have to go in the army. He is a proper rotter of a man.”

The anonymous letter which criticises Mr. Busby’s claim

The anonymous letter which criticises Mr. Busby’s claim

Busby lost his appeal and served in the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force between 1917 and 1918. He survived.

Appeals

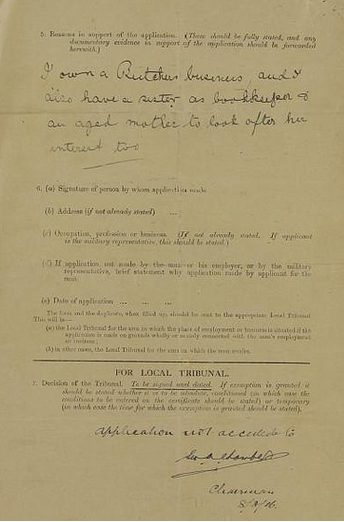

Another butcher, Aden Stone, was given just a day’s exemption after being found to have bought up a rival shop in an attempt to escape being sent to the front. He also served in the Royal Naval Air Service and later the Royal Air Force.

Aden Stone’s Appeal Form

Aden Stone’s Appeal Form

The most tragic case unearthed is that of John Gordon Shallis, aged 18. The plight of the Shallis family was recorded by the local paper and presented as evidence to the tribunal.

Elder brother George Victor died on the merchantman Vinknor leaving behind a wife and two children. Then within a couple of days brother Albert, 21, was killed in the Dardenelles and brother Harry, 19, of the King’s Royal Rifles died in the trenches of Northern France.

Before the appeal ended John had lost a fourth brother. The local paper said: “The Shallis brothers were finely built young fellows, standing six feet in height and before joining the Forces had all been doing well in civil life.”

John was granted an exemption to carry on working in the munitions industry and look after his mother and sisters.

The strain on large families is revealed in the case of the Baggs. Alfred Baggs appealed because he was married but agreed to fight so his younger brother, David, could run their farm.

But later David was called up anyway and then another brother was conscripted. Father William was so worried about his sons in battle that he drowned himself in September 1918 at Stanwell just two months before the end of the war. All his sons survived.

Resonance

Chris Barnes, Records Specialist at the National Archives, said: “It just shows the pressure that resonates today with families who have sons and daughters serving abroad.”

The road to conscription began in 1915 with the taking of a national register in August of all men and women aged 15-65.

It revealed just over five million men of military age not in the armed forces of which 1,489,798 single men were available for military service. But in September only 71,617 volunteered to serve.

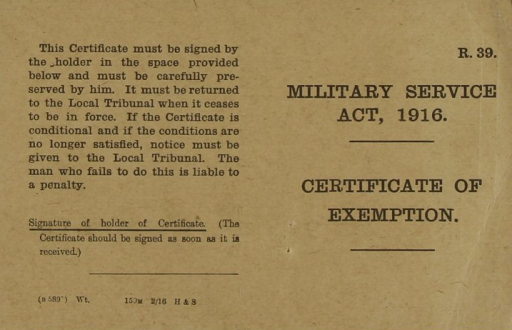

A recruitment scheme headed by Lord Derby produced only 343,386 new recruits and conscription was introduced with the passing of the Military Service Act in January 1916.

But there were some who refused to fight on moral grounds. Charles Cunningham wrote to the tribunal: “I should explain that my objective is not merely to the taking of human life but a much more fundamental objection to war as a whole.”

He was found agricultural work to retain his exemption.

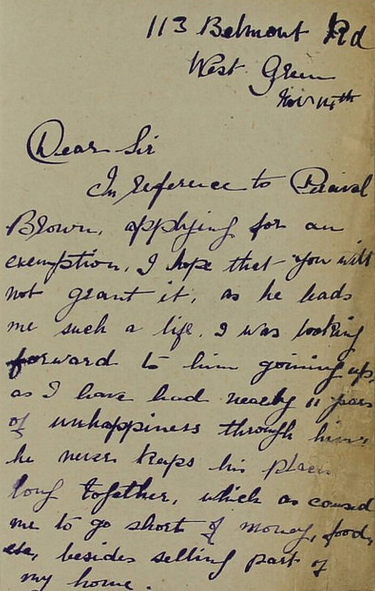

There is also a lighter side to the papers. The wife of Percival Brown wrote to the tribunal begging them to take him as he left her short of food and money.

She wrote: “Dear Sirs, in reference to Percival Brown applying for an exemption, I hope that you will not grant it, as he leads me such a life. I was looking forward to him joining up, as I have had nearly 11 years of unhappiness…”

Letter from the wife of Perceival Brown

Letter from the wife of Perceival Brown

David Lanngrish, reader adviser in the National Archives Advice, Records and Knowledge department told Centenary News: “The most interesting thing we have found is that the vast majority were appealing on domestic, business or financial grounds and not with a conscientious or war objection to actually fighting.

“More than half the cases from this tribunal were dismissed so they would have seen some service in the Army, Navy or Air Force. Applicants would have given their lives just like so many others did.

“Over the years there has been that shirker tag pinned on people who haven’t served in the two world wars. By digitising this collection we are enabling readers, researchers and historians to make up their own minds. It is a very sensitive topic.

“Some of the cases will pull at the heart strings while others will appears less dramatic but when you read them they begin to show the full impact of the First World War and how none of them could have been prepared for that.”

The Middlesex tribunal file series, known as MH 47 is one of only two appeal sets which survive in full. Due to the sensitive issues that surrounded compulsory military service during and after the First World War, most were destroyed.

The digitisation of the records has been supported by the Federation of Family History Societies and the Friends of the National Archives and forms part of the National Archives’ First World War 100 project.

Source: National Archives

Images courtesy of the National Archives

Posted by: Mike Swain, Centenary News