Dr. Jillian Davidson writes for Centenary News about the Western Front Association East Coast symposium.

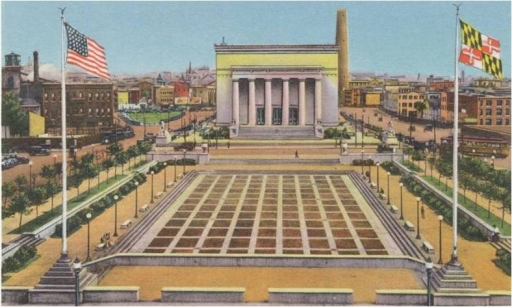

Chairman Paul Cora welcomed the WFA East Coast family back to Baltimore’s War Memorial Building for its biannual symposium on June 7th. Commissioned in 1919 and completed in 1925, the $1.1 million memorial paid tribute to the citizens of Maryland who gave their lives and services to their country in World War One. In 1977, the memorial was rededicated to those Marylanders who gave their lives in all of America’s wars in the twentieth century.

Acknowledging that Americans are in touch with the Civil War in a way that the British are in touch with the First World War, Paul Cora spoke about the challenges of contextualizing the Centenary for Americans. “There are WWI stories of Maryland that need to be told.” The story of George Buchanan Redwood, an alumnus of Harvard (the American college which provided the most soldiers in the war), an editor of the Baltimore News, and the first Baltimore officer to be killed, is one such story. The story of “Baltimore’s Own” 313th Infantry is another. Henry Gunther, one of “Baltimore’s Own” was the last soldier killed in the war, one minute before the armistice at 11am on 11/11/18.

Some Baltimore stories merit grander projects. Francis Warrington Gillet, who was born and died in Baltimore, flew with the Royal Air Force under the name of Frederick. His record of 20 victories ranked him as the second highest American Ace in the First World War. Paul Cora articulated his plan to commission an oil painting of Gillet, followed by a high media unveiling in the War Memorial Building.

Sarajevo 1914-2014

Three weeks, exactly, before the 100th anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, it was appropriate that WFA member, Steve Miller, presented a then-and-now look at the assassination trail. Steve Miller’s connection to WWI is also approaching a half-centenary since his interest dates back to the War’s 50th anniversary.

Steve Miller’s talk was based on his research of the events of June 28 1914 and his two Sarajevo trips, made in 1988 and 2010. His power point attested to the turbulence of change wrought upon Sarajevo. The city hall, for example, from which the Archduke began his last journey, was first opened in 1896. Converted to a national library in 1949, it still stood as such on Steve Miller’s first trip. But in 1992, the library was destroyed with its almost two million books. When Steve Miller returned in 2010, the building was under construction and, only a month ago, it reopened for Centenary commemorations.

Miller also showed photos of the Archduke’s automobile from the assassination scene, now enshrined at the Military Museum in Vienna and pointed out its rather uncanny number plate: A III II8 (which can easily be read/reconfigured as A 11 11 18) Mentioning the destruction of the footprints of where the assassin, Gavrilo Princip, stood, Miller commented: “They are, of course, symbolic, but lets not forget they gave us a reason for being here today.”

Dr. Bruce Gudmundsson, courtesy of Paul Cora

Dr. Bruce Gudmundsson, courtesy of Paul Cora

The Arms Race 1905-1914

The second talk of the WFA symposium also related to the run-up to War. The obvious arms race, more commonly discussed, is the dreadnought battleship race. Dr. Bruce Gudmundsson, of Marine Corps University, instead proposed “thinking inside the box” by way of reviewing the arms race on land. He did this through the lens of three individuals: Richard Burton Haldane, the British Secretary of State 1905-1912, Bruno von Mudra, the Prussian General of the Infantry and Joseph Joffre, commander-in-chief of the French Army as of 1911. All three were outsiders, and though Haldane was a philosopher and lawyer by training, Mudra and Joffre were engineers.

Haldane created and organized the Special Reserve and Territorial Force and thereby built up the infrastructure of the BEF. “He built a network by schmoozing for seven years to local notables, to all these Downton Abbey characters. This gave Britain the ability to train a national army.” It was done locally and to read about it, Gudmundsson explained, you would have to look at local newspapers. His reforms, like those of von Mudra and Joffre, look like footnotes before 1914, but they were responsible for building military infrastructure.

Canadian Court Martials

Moving away from the pre-war period, Teresa Iacobelli spoke about her book “Death or Deliverance. Canadian Courts Martial in the Great War.” She emphasized that this was more than an academic project for her; it was a moral pursuit. She sought to move beyond statistics and look at the individuals in order to add more truth to the social memory of the war.

According to statistics, 361 soldiers from the armies of Great Britain and its Empire were shot at dawn. 25 of these 361 were Canadians. (23 were executed for desertion and cowardice and 2 for murder). Iacobelli prefers to begin, however, with the story of one twenty-one year old, Arthur Lemay, a three-time deserter, who was sentenced to death. When it all but remained for Sir Douglas Haig to sign off on this sentence, Haig disregarded recommendations and commuted the penalty. Iacobelli wanted to find out whether the case of Arthur Lemay was the exception or the rule.

Commuted death sentences proved the backbone of Teresa Iacobelli’s research. As the first scholar to look at the commuted case files (197 cases in all), she found evidence of good officer-soldier relations, based on paternalism and trust. The system was fair and fluid, and although the commander-in-chief had the final say, he rarely acted against recommendations except for when he showed mercy. More decisive factors in the decision making process were the state of discipline in a soldier’s battalion and the timing of a desertion. If a soldier deserted just before an attack, he was more likely to be executed.

Even though the British Army was responsible for executing more soldiers for desertion than the Germany Army was (48 official recorded executions vs. 361), Iacobelli ultimately dismissed General Ludendorff’s claim that the Entente “achieved more” with their ruthless system of discipline and punishments. Allied victory, she argues, cannot be reduced to such a simple and limited explanation.

Aerial Reconnaissance

Jon Guttman, research editor for Weider History Publications and a prolific author of books such as “Balloon-Busting Aces of World War One,” offered another look at the background to war, but his view was neither from the sea nor land, but from the air. He recounted a series of firsts in his talk on “The birth of Aerial Reconnaissance.”

Guttman’s narrative began with the humorous anecdote attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Upon observing the first balloon ascension in 1783, someone asked, “What possible use are balloons?” Benjamin Franklin retorted: “What use is a newborn baby?”

The Italian Air Force was the first to use airplanes in combat missions during its war against the Ottoman Empire. On October 23, 1911, an Italian pilot flew over Libya conducting the first aerial reconnaissance mission. Italy also pioneered the first aerial bomb dropped on Turkish troops in Libya on November 1, 1911. In January 1912, the Italian airplanes set another precedent by dropping leaflet propaganda.

By the time World War One broke out, it was difficult even for conservatives to accept Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s dictum of 1911 that “Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value.” In fact, Guttman explained that the Russians were so badly defeated at Tannenberg in the first days of the war because on August 28, when aeroplanes came to play a part, all Russian aircrafts were facing the Austrian front and not the German. By contrast, the Germans deployed a significant force of reconnaissance airplanes on the Eastern front. The new toy demanded to be taken seriously.

The Mons Panel 1914-2014

The WFA symposium concluded with an extremely lively and instructive panel and audience discussion on the military, strategic and psychological significance of the battle of Mons. The panel included four military historians – John Guttman, Bruce Gudmundsson, Andrew Rolander and Alexander Falbo. In many ways, their debate neatly tied together all the themes of the day such as the question of how prewar German and British army preparations and training doctrines shaped their first confrontation on August 23rd, 1914.

Bruce Gudmundsson mentioned that he was still waiting for the French to weigh in and come out with their book version of this battle. But, as Jon Guttman pointed out, putting things into perspective, what happens to France does not necessarily determine the war. “I know that this is the Western Front Association, but this was a World War.”

The fact that the panel did not reach a consensus as to who won or lost the first battle indicates that the next four years of centenary commemoration and debate will be anything but dull.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author