Centenary News contributor Ottilia Saxl tells the story of her great-uncle John Miller Coutts Weir, who was awarded both the Military Medal in 1916 and Military Cross in 1917 and served in all three services.

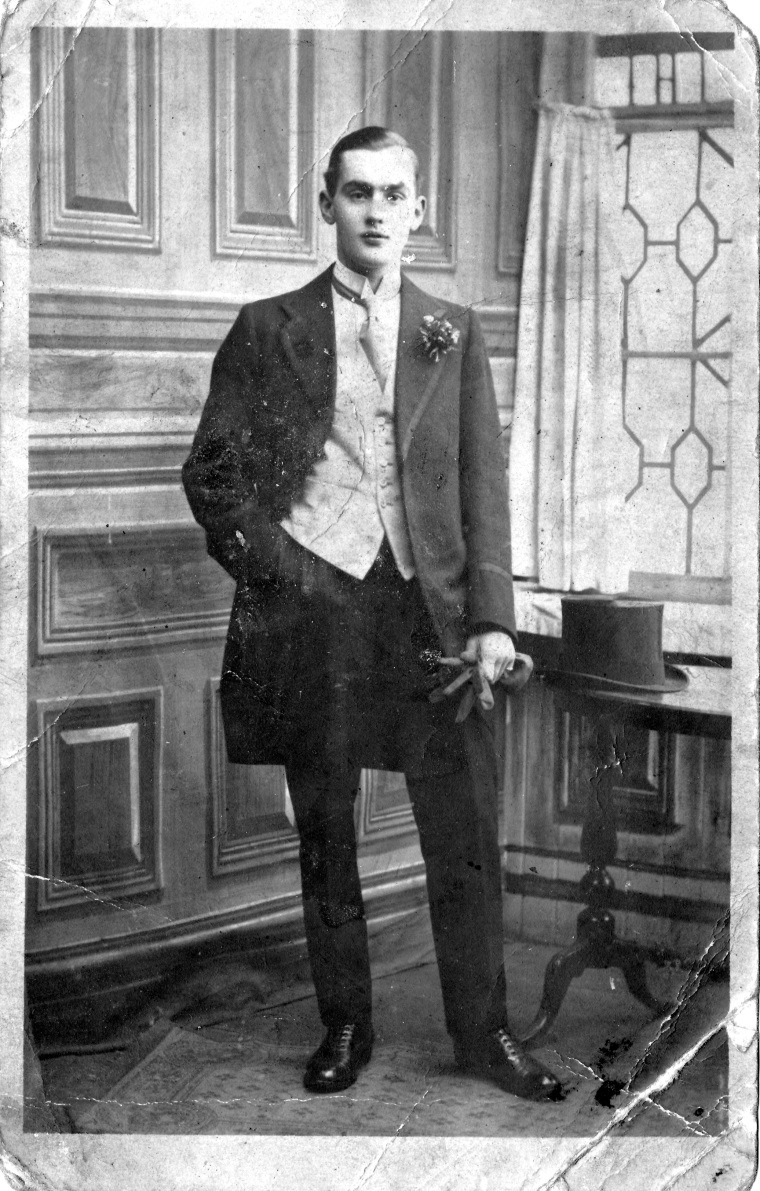

My journey started with a head and shoulders photograph of one of my grandfather’s brothers.

It was of a fine featured young man in a smart new uniform with a cap bearing a naval insignia. On the back, in my mother’s copperplate writing, it said: ‘John Weir, died of black water fever. Age 22’.

I was always a bit curious about the photo. Charisma can be captured through the lens, even by an amateur photographer. This was certainly the case for this particular image.

Rumour had it that the young man in question, whom I knew to be a great uncle, had died of ‘Black Water’ fever. I thought it quite sad for someone so young to die so far away from home.

I assumed he died during the First World War (my mother had written his age at death wrongly, it should have been 28), and once or twice over a few years I had a look for any action that might have taken place in Africa or India. There were some quite important skirmishes in Kenya, but that was all I could find.

John Weir – dressed for an occasion, probably his brother William’s wedding in Muirkirk, November 1913 (© Ottilia Saxl)

Who was John Miller Coutts Weir?

John Miller Coutts Weir was born in Selkirk in 1893. His middle names have been critical as they enabled me to identify him unambiguously in military and other records.

John was the fifth child and fourth son of Alexander Weir, a Master Saddler, and his wife, Margaret Coutts Miller. When John was only 4 his mother died, having giving birth to 6 children in quick succession.

That great loss might have turned into a worse tragedy had John’s father Alexander not quickly found himself a new wife, Elizabeth Mitchell. Elizabeth at only 23 was prepared to take on an established family, and she bore Alexander a further 6 children.

At age 16, John Weir joined the Commercial Union Assurance. Co. Ltd., 10 St. David Street, Edinburgh as an Insurance Clerk, and worked with them from 1910 to the end of 1914.

On January 23rd 1915 he went to Berwick-on-Tweed to volunteer for service with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

This Christmas (2013), an email appeared in my inbox from a genealogy company. ’30 units free on findmypast.com’.

Well, I thought, worth a punt. So I entered the name ‘John Weir’ and his approximate date of birth. The search turned up four John Weirs.

It was quite a shock to see that one was John Miller Coutts Weir. I hadn’t expected anything at all.

Now I was really astonished. Here was my great uncle, the shadowy picture in the photograph (Miller and Coutts were family names). I became determined to discover more.

The link led me to John’s military record. In black-and-white, and in stark terms, I could read that this hitherto unknown soldier, had won a Military Cross, and prior to that a Military Medal.

Although I had learned much about my family at my Granny’s knee, this increasingly extraordinary brother-in-law of hers had never been mentioned, although there were many stories about my grandfather, his brother.

My research turned up details of John’s award of the Military Cross, but almost none that I could find about the Military Medal.

From modest clerk to unlikely fighting man

John’s military records showed that he volunteered for the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) at Berwick-on-Tweed in January 1915, age 21.

In John’s records the first action documented was in that dreadful theatre of war called Gallipoli, where he went from 30 June – 10 October 1915. Once more, a dim window on the past took on bright new colours.

I wondered first about the dates. What was the significance of landing on 30th June? What about 10th October? Why did his record say he had left Gallipoli? – the action hadn’t finished then. Was he taken off because he was sick?

Dysentery

Everyone in Gallipoli at that time was sick. Dysentery and typhoid were rife, water was scarce, rations were inedible. There were flies everywhere. These conditions had continued almost since the beginning of the action in the Dardanelles, wearing the troops down inexorably.

But between July and September, some of the fiercest fighting had taken place, so this 23 year-old had had a baptism of fire.

Future battles of World War 1 were often measured against the horrors of Gallipoli, particularly the battle of Lone Pine, a major skirmish with massive loss of life in horrendous circumstances, which took place between the 6th and 10th of August.

The KOSB in action, Cape Helles, The Dardenelles, May 15 1915 (Courtesy Imperial War Museum © Q70701)

It was likely that John Weir saw his first action at the time of the Lone Pine debacle. Hand-to-hand combat took place in narrow, dark trenches, so awful that men from opposing sides died bayoneted together in a deadly embrace.

At Gallipoli, soldiers from both sides were at times commanded to run forward straight into enemy fire in broad daylight to be mown down as easy targets from guns ranged above or alongside. (What was the point of that, one wonders, in retrospect?).

Those of the KOSB who survived the nightmare may have had had some respite being stationed at Alexandria, until called on in February 1916 to fight in France.

But surviving one horror over a protracted period does not give you a free pass from what might lie ahead

John Weir was still serving in the 1st Battalion KOSB between September 1915, when he left Gallipoli, to the end of January 1916.

From early February 1916 to January 1917, John’s records show he served with 6th Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, as part of the B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force).

Marseilles

On the 18th March 1916, the KOSB arrived in Marseilles for service in France, likely in preparation for the Somme offensive, which lasted from July 1st to 18th November 1916.

The KOSB were also involved in action at Arras and Ypres. The Arras offensive started on the 19th January 1917, and the 3rd Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) began on 31st July 1917.

On the 22nd January 1917 John Weir’s award of a Military Medal gained in action in November 1916, when Acting Sergeant (Corporal), was reported in the London Gazette.

I cannot trace the report, but the medal may have been related to the last days of action on the Somme.

On the 27th June 1917, John is recorded as being granted a temporary commission as a Sub-Lieutenant in the R.N.V.R., for service in 63rd (R.N.) Division ‘with seniority’.

In October 1917 the 63rd Division moved north to the salient where Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) was in full swing. There are graphic descriptions of the conditions and the fighting during the attack on Passchendaele alongside the Canadians on 30th October.

On the 17th November 1917, John Weir is recorded as ‘embarking Folkestone, disembarking Boulogne’ where he joined the base depot at Calais, presumably on his way to the action at Cambrai, and thence to Welsh Ridge, where his courageous efforts result in the award of a Military Cross.

Welsh Ridge

The Military Cross was won in December 1917 at Welsh Ridge, a skirmish that took place at the tail end of the Battle of Cambrai, where I later discovered, tanks had been successfully deployed by the British for the first time, and so had secured its place in military world history.

The action at Welsh Ridge is quoted in many publications. John’s medal citation reads:

The Edinburgh Gazette – MC Announcement

Publication date: 19 August 1918

Issue: 13305, Page: 2896

T./Sub Lt. John Miller Coutts Weir, M.M., R.N.V.R.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When the enemy attacked after an intense bombardment and penetrated part of his line, he kept his men well in hand and fought every inch of ground. He led a counter-attack, drove the enemy back to their own lines, and reorganised the position. He held his ground against several further attacks under heavy fire, and inspired his men throughout by his determined and courageous leadership.

The Hood Battalion citation is more telling:

“On 30th Dec. 1917, in the attack on WELSH RIDGE, when the enemy with his storm-troops pierced part of our line, this officer showed great gallantry in leading his men. In spite of the intense barrage he kept his remaining men together & fought every inch of ground. Although he had his revolver blown out of his hand he remained unshaken & threw bombs at the enemy. He went back for reinforcements & more bombs & organised a bombing party to push back the enemy. It was mainly owing to his leadership & organisation that the enemy were forced to withdraw. He forced the enemy right out of the sap & back to their own lines & reorganised men to hold the sap. During the next 48 hours, when the enemy attacked on several occasions after heavy artillery preparation, he displayed great courage & coolness throughout the whole period, helping & encouraging his men the whole time. He came out of action with 8 men only.”

A Blighty ticket

John’s records show that from 07.04.18 – 18.4.18 he was promoted to Acting Lieutenant in the Hood Battalion. The promotion was short-lived as on 14th April 1918, eleven days after his 25th birthday, he received a serious gunshot wound to his left elbow.

This may have been in action around Mesnil, in the Ancre Valley, where the Hood Battalion is recorded as being stationed that April.

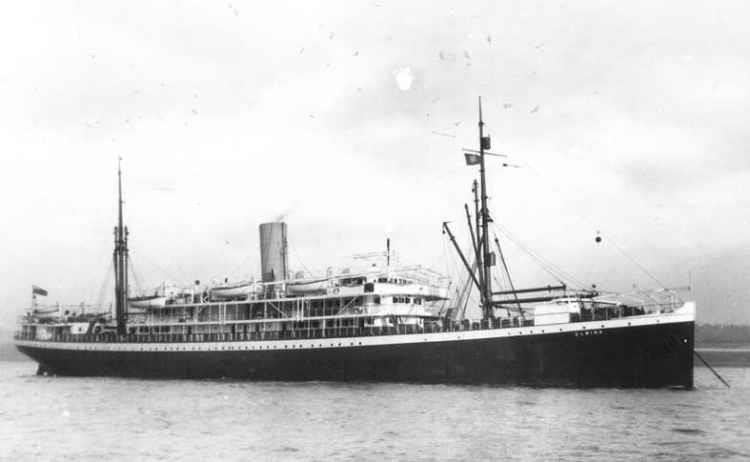

On the 17th April he is admitted to the 2nd Red Cross Hospital in Rouen, and on the 21st April, he is invalided back to the UK, travelling across the Channel , bizarrely on the “Grantully Castle” Hospital ship, the same one that was deployed to treat the wounded in Gallipoli – in what must have seemed like a lifetime ago. What stories that ship could tell!

H M Hospital Ship, Grantully Castle, off Salonika, 1915. Courtesy of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

H M Hospital Ship, Grantully Castle, off Salonika, 1915. Courtesy of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

On April 22nd, John Weir was admitted to the 3rd Southern General Hospital in Oxford. On the 1st May he was assessed by a Medical Board, and deemed unfit for active service for 2 months. Now out of action, his Hood Battalion record states he ‘relinquishes the pay of acting rank of Lieut RNVR as he has ceased to command a Company’, but nonetheless he retains his rank, and is entitled to wear the badges of that rank.

On the 16th May, after only a fortnight, the Medical Board surprisingly pronounced John ‘fit for general service’ and grant him three weeks leave, before rejoining the 2nd Reserve Battalion at Aldershot on 7th June – which he duly does.

His records then show some interesting entries. Around this time, he applies for a transfer to the Royal Air Force, and between the 25th June and 20th July, he successfully completes a 1st Class Rifle course at Aldershot. He must have thought that marksmanship could come in handy!

Immediately (23rd July) John is sent on ‘draft conducting duty’ in France, returning on the 31st – still with the 2nd Reserve Battalion. Draft conducting apparently means that officers accompany groups of soldiers to help them find their units. Shortly after returning from France, there is quite a comical entry: “Attended 4 days Gas Course from 06.08.18 but found unlikely to make a good anti-gas instructor”.

Pilot

On the 8th of August, John’s transfer to the Aeronautical College is effected. On the 24th August he is sent to the No. 1 Officer’s School at Brocton Camp in Staffordshire presumably to learn aeronautics.

He is there until the 19th October, where he obtains a ‘satisfactory report’. By the 28th October, John is noted as going to the School of Aeronautics, RAF Reading. His record then reads: “Taken on strength from 2nd Reserve Battalion. 05.11.18, whilst attached RAF Reading”. He continues at the Aeronautical College until 3rd March 1919.

He doesn’t seem to have set the heather on fire as a potential pilot, but maybe as someone who has seen so much action he doesn’t suffer others telling him what to do. Who knows??

I get the feeling that for most of 1918, John Weir’s superiors are being kind to him, by sending him on courses and less dangerous assignments.

Maybe they recognised that he had spent nearly three years in the worst theatres of the First World War and had acquitted himself well – and your luck can run out.

Maybe that is just wishful thinking.

The Sting in the Tail

From spring 1918 to the end of hostilities to spring 1919, John, now thankfully away from the front line, is back in Blighty and attached to the RAF.

Here is a man, 25 years old, in the prime of his life, who has been tested in the furnace of war, and faced mortal danger countless times. He has no young lady waiting for him, or to go home to, and very few opportunities to meet girls, so naturally enough he does what probably many of his mates do – he visits the local Madam. What has he got to lose?

Unfortunately, quite a lot. It is such a paradox, that a battle-hardened young man, like many of his contemporaries, is completely naïve when it comes to sex.

On the 31st March 1919 he is sent to Brighton Grove Military Hospital in Newcastle, suffering from syphilis. Still with the army, he is classed as ‘unfit for general service for 2 months’.

On the 28th May, he is given the all-clear, and discharged from hospital.

It must have been a sad time. In spite of all his honours, he probably didn’t want to admit to his family why he was in hospital. They wouldn’t have understood.

John is back with his battalion the day after his discharge, on the 29th May. Things move quickly. On the 4th June he is ordered to the Dispersal Station at Kinross, for demobilisation.

Demobbed

Officially demobbed on Friday 6th June 1919, he is given medical category “A1”. (I’m not sure whether that means he is 100% fit, or fit enough to go back to his pre-war occupation as a clerk, or fit enough not to claim disability.).

John’s story does not end there.

Who knows where he gets the idea or opportunity that takes him to the next stage of his life? But about two months after demob, on 13 August 1919, he boards the SS Elmina in Liverpool, bound for Nigeria.

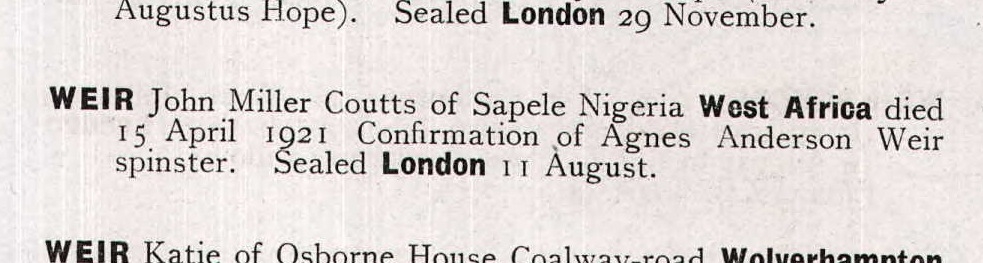

Excerpt from passenger list SS Elmina 1919 with JMC Weir on the list

Excerpt from passenger list SS Elmina 1919 with JMC Weir on the list

I wonder what it was like for this recent war veteran to travel for once on a ship where the fresh air could be appreciated, and the view of the sea and sky untainted with thoughts of possible terrors ahead? Was it for John a wonderful feeling of freedom, travelling to a future that did not include war?

Or was it, that once the anxiety that each day used to bring had gone, there was time to process and be haunted by the horrors of his experiences , that till now had been kept well at bay?

Voyage to freedom, SS Elmina.

Voyage to freedom, SS Elmina.

John landed in Nigeria in September 1919 and makes his base in what was the heartland of the mahogany timber industry in 1919 – Sapele. He also travels to Sierra Leone, sending home letters, photographs and even a carved mahogany table. There is a wonderful staged photo of him posing with a colleague and forestry workers that he sends to his brother, Anderson.

John Miller Coutts Weir (seated, right) Sapele 1920 (© Ottilia Saxl)

On the back of the photo, in Anderson’s writing, it reads: “Hello, Mother, One for you, one for Jennie and one for Willie, and I have one. You will see I often think of John.”

The End

West Africa is fraught with danger from a deadly enemy that cannot be killed by a bullet, bomb or mine. An enemy that is often too small to see.

And so the mystery that started my quest was eventually solved. On the 15th April 1921, John Miller Coutts Weir, MM, MC, did indeed die of Black Water Fever, otherwise known as malaria, in Sapele, Nigeria.

He had just turned 28.

© Ottilia Saxl

Posted by Mike Swain, Centenary News