The story of how Britain’s codebreaking skills were pioneered during the First World War is explored in a new exhibition at Bletchley Park.

The former intelligence centre is best known for cracking the German Enigma code in the Second World War.

But The Road to Bletchley Park’ aims to show that the foundations were laid in WW1.

A large number of those involved in signals intelligence went on work with the UK’s newly-formed Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) in 1919.

When war broke out again in 1939, they moved from London to Bletchley Park, a mansion in the safety of the Buckinghamshire countryside.

Among the code breakers was Alfred Dillwyn ‘Dilly’ Knox. The Cambridge classics don joined the Admiralty’s Room 40 section in 1914 and went on to lead the GCCS team, including Alan Turing, that made the first operational break into Enigma in 1940.

The Duke of Kent (centre) touring the exhibition with Sir John Scarlett (first left), Chairman of the Bletchley Park Trust, and WW1 research coordinator, Dr Sarah Ralph. Codebreaker ‘Dilly’ Knox apparently did some of his best thinking while having a bath (Photo ©ShaunArmstrong/mubsta.com).

The exhibition was officially opened by the Duke of Kent, Bletchley Park’s Royal Patron, on July 29th 2015.

Sir John Scarlett, Chairman of the Bletchley Park Trust, said it was an ‘essential part of the Bletchley Park story.’

“The Great War took place at a time of rapid technological change and innovation. Cable, wireless, codes and codebreaking were central to this revolution,” explained Sir John, a former chief of the British intelligence service MI6.

“The work of British interception and codebreakers achieved outstanding success. As in World War Two, our country was at the cutting edge of technology, where it always needs to be.

“In the Great War the foundations were laid, and the leadership prepared, for the triumphs of Bletchley Park.”

The first phase of the exhibition, introduces Britain’s two very distinct WW1 codebreaking operations: MI1(b), set up by the War Office, and the Royal Navy’s Room 40. Behind the scenes in London offices, both waged a secret war.

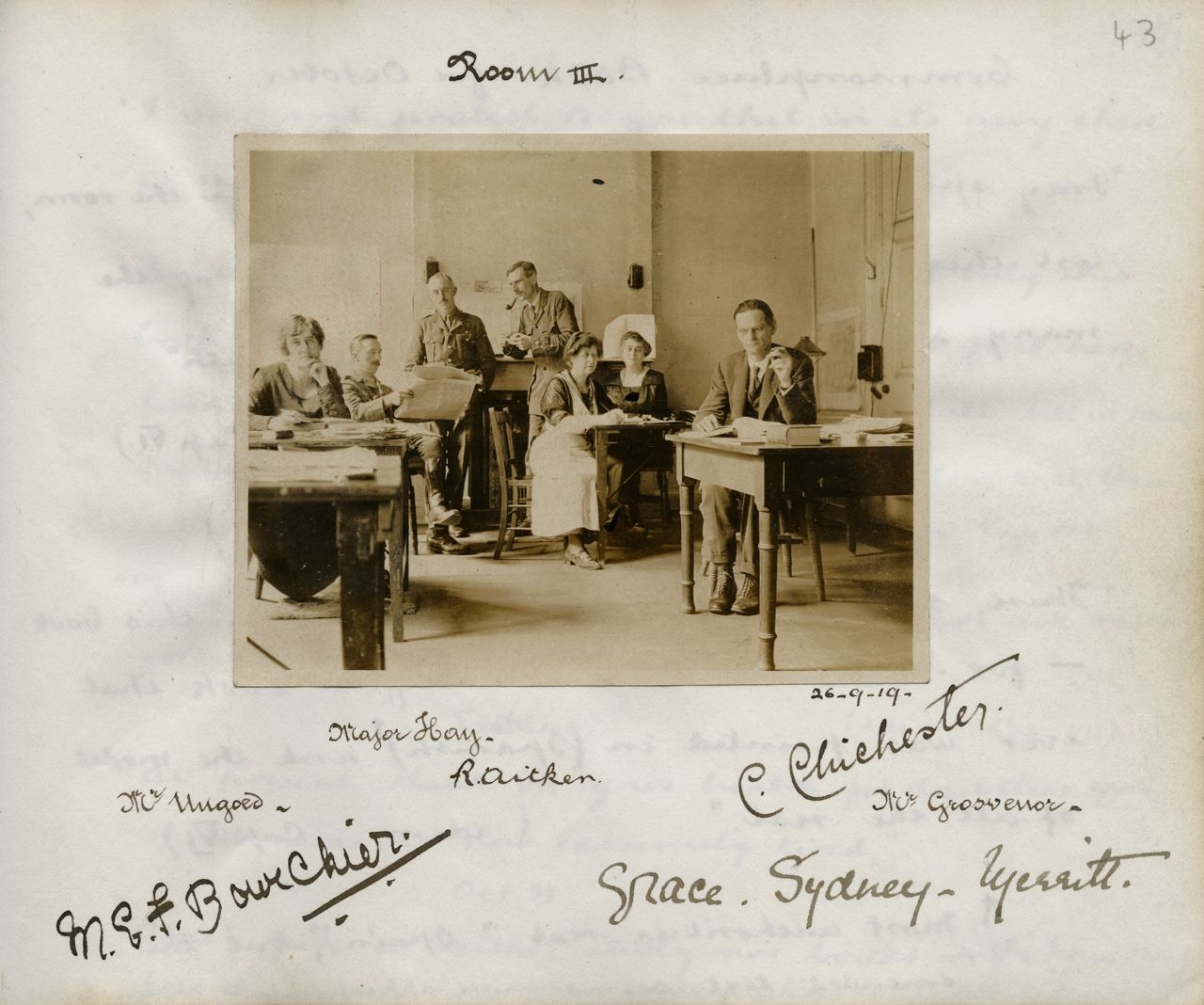

(Image : University of Aberdeen, Papers of Malcolm Vivian Hay of Seaton, MS 2788/2/17)

(Image : University of Aberdeen, Papers of Malcolm Vivian Hay of Seaton, MS 2788/2/17)

Each organisation had its own hierarchies and objectives, and was dependent on the brand new technology of the day. One of the main Bletchley exhibits is a replica Marconi crystal receiver listening set.

Dr Sarah Ralph, Bletchley Park’s WW1 Exhibition Research Coordinator, said: “Both Allies and Central Powers used cable and wireless telegraphy to intercept messages and deduce enemy tactics and positions. Each side tried to break the other’s codes and gain valuable intelligence.”

More traditionally, she explains that Room 40 kept a copy of Jane’s Fighting Ships, a reference book exhaustively cataloguing the warships of every nation.

“Every time a ship was sunk (Room 40 staff) would cross out the name. It’s a very physical way of marking the conflict’s progress.”

The exhibition also delves into the stories of some of the key characters involved in codebreaking during both world wars.

Paying her own tribute to the signals intelligence pioneers, Dr Ralph said: “Their efforts from 1914 to 1918 allowed the codebreakers to hit the ground running at the outbreak of WW2.”

‘The Road to Bletchley Park’ runs until 2019 in the Block C Visitor Centre at Bletchley Park, near Milton Keynes.

Source: Bletchley Park Trust

Images courtesy of ©ShaunArmstrong/mubsta.com (Duke of Kent); University of Aberdeen, Papers of Malcolm Vivian Hay of Seaton, MS 2788/2/17 (Room III); Centenary News (Bletchley Park mansion)

Posted by Peter Alhadeff, Centenary News