In a special article for Centenary News, Tim Butcher, author of The Trigger – Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War, reveals the myths and historical mistakes which surround the story of gunman Gavrilo Princip who shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28 1914.

CAN THERE be any key figure in history whose story has been more muddled, mangled and misrepresented than Gavrilo Princip?

The basic narrative we all know well enough: Princip was the teenage gunman who shot dead Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, the incident that triggered the First World War.

But the details of who Princip was, his motivation, his actions and his support network have been mired ever since in complacent research, ethnic rivalry and political bias.

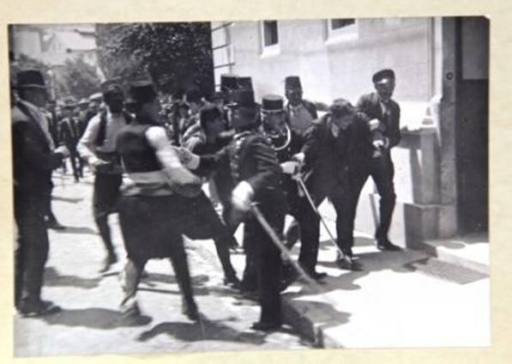

There can be no better symbol of this muddle than the `Princip arrest’ photograph that purports to show the young assassin being bundled away by Austro-Hungarian gendarmes that summer’s day.

Truth

It has already been used by newspapers and broadcasters in the run-up to the centenary of the shooting. Cambridge University Press is due to use it on the cover of its authoritative new history of the July 1914 crisis.

But the truth is it does not show Princip.

For me establishing Princip’s actual story was one of the primary motivations behind the years of research and writing that went into my new book: The Trigger – Hunting the Assassin who Brought the World to War.

I wanted to fill out the figure who ghosts only half-formed into the received account of how the First World War began.

In part, I wanted to see what the historical record actually shows, not what the bias of later observers project onto the story. I wanted to establish the nature, extent and strength of genuine evidence.

But I also wanted to touch on the issue of the origins of the First World War, in particular the debate over which side was responsible.

Basic mistakes

The debate remains arch with views as divergent as Max Hastings’s (who repeats the `Germany was wholly to blame’ version) and Christopher Clark’s (who clears Germany of sole responsibility).

Those in this debate pay scant attention to Princip, indeed they again make basic mistakes with the narrative of the assassination.

Perverse

This continues to strike me as perverse given that the Sarajevo Attentat sits as the founding sequence in the genetic code of the First World War narrative.

Until you get that right, can it be possible to understand properly the origins of the conflict, let alone reach closure for all the sacrifice and suffering it entailed?

When I embarked on the project it soon became clear that material on Princip was not in short supply.

In 1960 a bibliography was published that simply listed all books, articles and papers referencing the Sarajevo assassination. It was 547 pages long and had more than 1,200 entries.

And like popcorn jumping from hot oil, writing about the incident has continued to emerge in the decades since that bibliography came out.

But what was in short supply, it soon became clear, was reliable material on Princip.

No truth

For example we have been told by authors, analysts and filmmakers in recent years that: Princip jumped on the running board of the Archduke’s limousine to take his shot;

The Archduke’s wife was pregnant when she died;

The shooting happened on the anniversary of their marriage;

The car did not have a reverse gear so was incapable of correcting the driver’s error;

The Archduke caught the grenade thrown earlier at the couple and tossed it away safely;

And Princip stopped to eat a last sandwich at the corner café before emerging to take his shot.

Good dramatic stuff this might be. Historical truth it is not.

Dross

So to research The Trigger I took a figurative sieve, the sort a Klondike gold prospector might have used, and filled it with all the accounts of Princip, colourful, contradictory no matter, and shook it vigorously.

An amazing amount of dross fell away but it did leave enough sound material, some from primary sources, others from writers who created reliable secondary source documentation, to build up a convincing picture of Princip.

I spent a long time in archives. In Istanbul the old Ottoman archives gave a flavour of what life was like for Princip’s forebears living for centuries under Osmanli occupation.

In Austria police documents from the 1914 Austro-Hungarian police investigation into the assassination are available in facsimile form, the originals having been lost some time after its last confirmed sighting in June 1915.

In Sarajevo and Belgrade a plethora of archives contain other material, much of it duplicative, some irrelevant. But the challenge was to keep panning until nothing but reliable nuggets were left.

Innocent bystander

In one of the Sarajevo archives, for example, it is possible to find the original of the `Princip arrest’ photograph correctly captioned with the name of the person being bundled away.

He was an innocent bystander, a man called Ferdinand Behr, an inhabitant of Sarajevo, who was picked up by the police simply because he tried to stop a mob on the pavement from beating Princip to death.

He published an account of the arrest in 1935 after seeing himself in a picture repeatedly captioned in error as Gavrilo Princip. He expressed his surprise that the mistake was made as he was so much taller and broader than the famously short and wiry Princip.

But I also found primary historical material concerning Princip not touched by a century of historians.

As a secondary school student in Sarajevo at a time when it was occupied by Austria-Hungary, Princip’s school reports were diligently recorded in hardback ledgers which have sat, undisturbed by researchers, ever since the Edwardian age.

Goose-bump moment

Seeing them was a goose-bump moment, bringing alive the young boy from a remote farming community sent to study in the big city of Sarajevo.

They allowed me to prove what other historians had only been able to infer: It was during Princip’s schooling that he lost his way after starting out as an A-star student graded `excellent’ in almost all subjects.

Worsening grades

This was charted clearly in the worsening grades logged by his teachers, blissfully unaware of how much bloody impact their failing student would have one day.

By going back to his farm village in remote western Bosnia and tracking down members of the Princip family today, I learned the lore of the clan.

It was not one hundred per cent reliable in historical detail but what it did do, more than traditional histories, was convey the key influences that impacted on the young boy who would become a slow-burn revolutionary.

Princip’s anger

To sit with a pensioner in the 21st century and hear the names of Princip’s six siblings who died in infancy more than a hundred years before because of the dire conditions of penury exploited by Austro-Hungarian colonial rule, was to begin to understand where Princip’s anger came from at a symbolic figure such as Franz Ferdinand, an anger that could plausibly mutate into violence.

But what was most striking for me was the discovery that there was no evidence to support Vienna’s claim that Princip was an agent of Serbia, the grounds given in July 1914 for Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on its small, troublesome neighbour.

This was key strategic act that drew in the Great Powers to four years of slaughter in the trenches, the multiplier that spun a localised Balkan assassination into a global conflict.

And yet there remain no reliable grounds in the historic record to justify Vienna’s claim.

Extremists

Princip spent a few months in Belgrade, capital of Serbia, and there he met extremist nationalists who helped arm him and smuggle him back to Sarajevo.

But it does not follow these extremists were backed, authorised or even known about by the Serbian government.

Vienna’s attack on Serbia had about as much legitimacy as a declaration of war by Britain on Ireland as retaliation for Louis Mountbatten’s murder in 1979 by Irish nationalists.

The best evidence on record shows Princip not as Serbian nationalist but a Slav nationalist, committed to liberating all locals, known as South Slavs, whether they be Croats, Muslims, Slovenes or Serbs, then under the control of a foreign occupier, Austria

Unproven claims

It is an important difference that undermines completely the stance by the hawks in Vienna that said an attack on Belgrade was justified retaliation for a Serbian plot to kill the Archduke.

Yet just as with the incorrect photograph of the arrest, historians have often repeated these unproven claims to portray Princip as an agent of Belgrade.

Wilfred Owen wrote of the patriotic invocation dulce et decorum est pro patria mori as `the old lie’, but I have come to see an even greater lie at the founding moment of the First World War.

It is the lie used by Vienna in its deliberate misrepresentation of the Sarajevo assassination and the role of history’s most misunderstood assassin, Gavrilo Princip.

Tim Butcher is the author of The Trigger – Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War, out now (Chatto & Windus).

Read more about Tim’s book The Trigger in our books section here

Tim will be discussing Gavrilo Princip at Southwark Cathedral in London on 25th June 2014.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author