Dr. Jillian Davidson writes for Centenary News about a new exhibition which has opened in New York to mark the Centenary of the First World War.

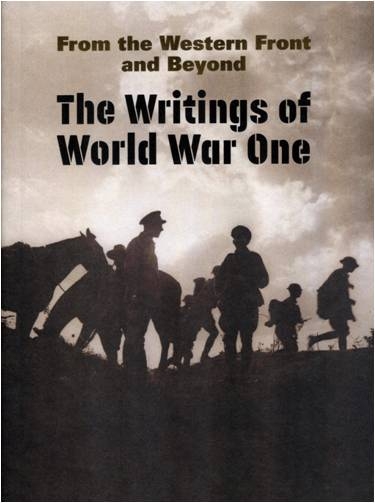

The New York Society Library, the city’s oldest library and one of the country’s earliest bastions of literary culture, proudly presents the first exhibition in Manhattan to mark the centenary of the First World War. On display to the public until November 15, 2014, “From the Western Front and Beyond: The Writings of World War One” pays homage to the literary legacy of the war.

This small, but artfully curated, exhibition tells of several intertwined stories: the first is the chronological and geographic scope of World War One literature; the second is the devastating toll and landscape of the war; the third is the library’s involvement in amassing this literature and the fourth and perhaps most moving is the personal losses suffered by the library’s members.

At first glance, the four glass cases show an interesting menagerie of books, but upon closer observation, the arrangement of artifacts amounts to a shrine of the book and of the soldier-writer. The Peluso Family Exhibition Gallery, with its arching ceilings, and illuminated war manuscripts, recreates the atmosphere of a Cathedral vault. Just a few steps beyond this vault, stands another shrine which houses a rare 1527 Cologne edition of Thucydides’ Historiographi de bello Peloponnensium.

The gallery’s North Arch, courtesy of Dr. Jillian Davidson

The gallery’s North Arch, courtesy of Dr. Jillian Davidson

Although the United States did not enter the war until 1917, Head Librarian, Frank Bigelow was quick to seize upon the avalanche of war writings. At the start of war in 1914, the Western and Eastern Fronts remained remote, but the publishing front attracted the library’s attention and stimulated activity.

The Early Acquisitions

The first glass case contains nine books published between 1914 and 1919. Five of the authors wrote for the British government’s War Propaganda Bureau: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame, America’s first war journalist Richard Harding Davis, the first female journalist to visit the Western Front, Mrs. Humphrey Ward, author of The Jungle Book Rudyard Kipling, the poet John Masefield and the historian Arnold Toynbee. Toynbee’s The German Terror in Belgium: An Historical Record lies open to a map of “The Invaded Country,” significantly stained bloody red. Mounted, right above the glass-enclosed display desk is a poster board with an excerpt from Rupert Brooke’s poem “The Soldier,” part of a letter from Vera Brittain in Testament of Youth, and a haunting photograph of The Somme taken by museum curator Harriet Shapiro in March 2013. The fact that the poster board dwarfs the case of “official” accounts of the war graphically suggests the seismic shift which takes place as a result of the war: the 2,500 year old tradition of state-controlled war narratives was replaced by anti-war literature somewhere along the Somme.

The New Poetry of War

The second glass case holds six books published from 1917 to 1927. As the billboard above this case indicates, the authors of these books represent the real personae dramatis of The Western Front and Beyond. The billboard states: “Time has softened the outlines of trenches that once snaked the battlefields of Europe and beyond. But the terrible beauty of the literature spawned by World War One lives on.”

Several of these poets died in the war such as the American poet, Joyce Kilmer (1886-1918) whose book lies open at its title page, with his photograph on the opposite side. Similarly, the poetry book of John McCrae (1872-1918) lies open at his photograph, as does the poems of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) and Edward Marsh’s memoir of Rupert Brooke (1887-1915). Siegfried Sassoon’s book of poems, by contrast, rests open at “Two Hundred Years After” and “They,” and Robert Graves’ Poems remains shut. And yet, photographs of both Sassoon and Graves feature in the collage of prominent figures, which borders the promotion poster above. Their profiles are as important as their writing.

Quentin Roosevelt

Quentin Roosevelt

The Library’s Personal War Story

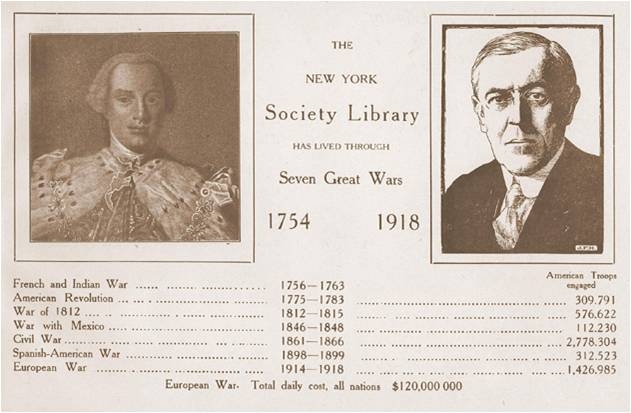

In between the second and the third glass case, on the wooden door beneath the North Arch, stands a full-bodied photograph of Quentin Roosevelt, the youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt and his wife Edith, who were members of the Library. A pilot in the 95th Aero squadron, he was killed in the skies over France. His photo introduces the visitor to the more personal chapter of the Library’s war involvement found in the third glass case. Enclosed herein are a photograph of Frank Bigelow, Head Librarian during and after the war, an announcement listing the Seven Great Wars that the Library had lived through from 1754-1918, a notice of the Library building’s closing in January of 1918 because of the scarcity of coal, and a bulletin of New Books, cataloguing the “Books on the European War” in early 1917. On another poignant note, Victor Chapman, grandson of library member Mrs. E. Jay Chapman’s, was killed in the skies over Verdun in June 1916. His Letters from France belongs in this part of the exhibition, as does the novel written by the son of another Library member. Humphrey Cobb’s Paths of Glory was made into the acclaimed Stanley Kubrick film in 1957.

A notice from the New York Society Library during the war, courtesy of the New York Society Library

A notice from the New York Society Library during the war, courtesy of the New York Society Library

Literature Beyond The War Years

In the fourth and final glass case are six books published between 1921 and 1958, which certainly attest to the international extent of the war’s enduring literary legacy. Although Czech humorist Jaroslav Hasek, author of the buffoon-like adventures of The Good Soldier Schweik (1930 edition), is the token Eastern European soldier-writer present at the exhibit, the Library explains carefully the significance of each selected work. American John Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers (1921 edition) is on display because it “addresses the brutality of the war machine and its influence on the masses. Turned down by fourteen publishing houses, it was finally accepted by the publisher George H. Doran. Dos Passos’s searing anti-war story caused, in the words of one reviewer, a ‘grandiose rumpus.’” Regarding Her Private’s We (1930 edition), “Australian writer Frederic Manning turned to Shakespeare for the title and chapter headings of this remarkable novel, considered by many critics the finest to emerge from the war.” Last but not least, concerning a 1958 edition of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, “The novel’s success was unprecedented; its harsh neo-realistic style captured the universal horrors of war waged by the common soldier… Burned by the Nazis, (it) remains the best-known novel to emerge from the ashes of the Great War.”

Cover of the catalog for From the Western Front and Beyond: The Writings of World War One, featuring essays by Adam Kirsch (Why Trilling Matters), Caroline Alexander (The War That Killed Achilles) and curator Harriet Shapiro. Courtesy of the New York Society Library

Cover of the catalog for From the Western Front and Beyond: The Writings of World War One, featuring essays by Adam Kirsch (Why Trilling Matters), Caroline Alexander (The War That Killed Achilles) and curator Harriet Shapiro. Courtesy of the New York Society Library

It was almost obligatory for an exhibition, which lays claim to its Library’s very active and involved connection to the War’s literary publications and to the power of institutional memory to follow and shape public memory, to produce its own publication to mark this Centenary. Accompanying the exhibition is, accordingly, a catalogue of thoughtful and informative essays collected under the same title as the exhibition. On the Library’s website, also in conjunction with the exhibition, is an in-depth World War One-related staff recommended reading list. The Library is also hosting for its members a series of four monthly seminars on the literature of the Great War. All in all, this is an exemplary exhibition to commence the Centenary in New York.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author