Centenary News Contributor Tom Hopkins tells the tale of three survivors from the British Navy of the First World War.

The trenches may hold a more prominent position in the public consciousness than the naval aspects of the First World War, but the three British warships that still survive from 1914-1918 look poised to tell the story of the war at sea and how the country was almost bought to her knees.

On 31 May 1916, the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet engaged in combat off the coast of Jutland. What followed was to be the most significant action at sea in the whole of the First World War, and the largest naval battle in history.

Since 1914 the Royal Navy had adopted a strategy of blockading German ports from afar. While the ensuing hunger and shortage in raw materials had a significant effect upon the German war effort, it was not in itself enough to win the war for the allies.

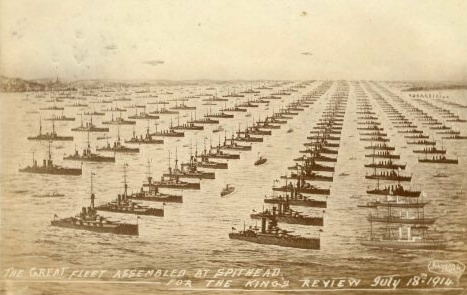

Postcard of the assembly of the Grand Fleet for the King’s review (public domain)

Postcard of the assembly of the Grand Fleet for the King’s review (public domain)

The Battle of Jutland

The German high command saw that a successful confrontation with the British at sea would not only raise the blockade but also have the potential, should they gain control of the Channel, to sever Britain’s vital logistical arteries into France.

The British could be knocked out of the war by the defeat of their navy, while Germany could not be defeated at sea alone. Churchill was apt to call Lord Jellicoe, the British Admiral of the Fleet: ‘The only man on either side who could have lost the war in an afternoon.’

A naval confrontation would not have proved easy for Germany – the British held the numerical advantage in dreadnoughts by a ratio of 21:13. If the German navy was to succeed, it would need guile as well as courage.

The Germans set a trap: they despatched a small force of battle-cruisers away from the main force of their High Seas Fleet to act as a lure for a similarly sized British squadron commanded by Vice Admiral Beatty. By then bringing their main fleet into the fray, and positioning submarines to cut off the escape for Beatty’s squadron, the Germans hoped to destroy a sizeable portion of the British Fleet.

Things did not quite go to plan. In one key aspect, the British held the upper hand. Earlier in the war, Russian sailors had recovered the body of a German naval officer from the Baltic. Among the dead man’s possessions was a copy of a German codebook that the Russians duly passed on to the British.

The British could intercept and decipher the Germans’ communications and by the end of May 1916 they knew that something was afoot in the North Sea. Beatty’s force did not steam into battle alone; it was shadowed closely by Jellicoe’s, with the bulk of the British fleet, ready to speed into action.

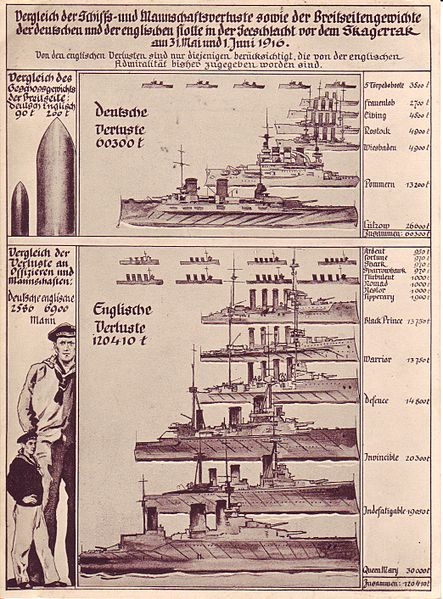

For the first time in the war, battleship engaged battleship. By the next morning 175,000 tonnes of shipping had been sunk with the loss of over 8,500 lives. The result was inconclusive – although more British ships were sunk, Germany could not deliver her knock-out blow. Both fleets sailed home, never to fight a major action again for the rest of the war.

German propaganda postcard comparing British and German loses at the Battle of Jutland (public domain)

German propaganda postcard comparing British and German loses at the Battle of Jutland (public domain)

HMS Caroline

Some 250 combat ships took part in the Battle of Jutland, of which 225 were still afloat by the morning of 1 June 1916. Despite the number of vessels involved only one survivor remains to this day.

HMS Caroline, a C-class light cruiser launched in 1914, was moored permanently in Belfast and adapted for use as a training ship in the 1920s – a role that she continued to fulfil until 2009.

Officially decommissioned in 2011, her future was uncertain until in May 2013 the Heritage Lottery Fund announced a first-round grant of £845,600 for a project to see the ship conserved and transformed into a floating museum.

HMS Caroline, courtesy of Wikipedia

HMS Caroline, courtesy of Wikipedia

What future form the Caroline will take has not yet been announced. Her appearance has certainly changed a lot since her combat days, having been stripped of her propulsion and weapon systems, and an unsightly drill shed added to the stern of her main superstructure.

It seems likely that it would be prohibitively expensive to restore her to her First World War appearance. However, as an exhibition space she clearly has much to offer – a recent statement has announced an academic partnership, focusing on the Caroline, between the National Museum of the Royal Navy with the University of Birmingham’s Human Interface Technologies Team, and we are told to expect ‘some very stimulating ways in which computer technologies and virtual environments can be brought to bear in telling the naval story’.

The status of the Caroline in the 21st Century as sole survivor of the Battle of Jutland reflects a wider general picture of a dearth in extant combat vessels from The First World War. In the UK today, there are only two others – and all three are looking to be part of Centenary projects and commemorations.

HMS M33

HMS M33 is a monitor – a type of small ship with disproportionately large guns, designed primarily for coastal bombardment. Launched in May 1915, it was not long before M33 saw active service – by August she was shelling Turkish positions in Gallipoli in support of the British landings at Sulva Bay.

The real strength in the configuration of a monitor in such an operation was not through any advantage conveyed by her small size in terms of speed or manoeuvrability – indeed, M33 was a good 10 knots slower than the latest cruisers such as the Caroline – but in terms of damage limitation. With her twin six-inch guns, she packed a punch, while offering only a small and relatively inexpensive target to any enemy fire returning from the Turkish shore batteries.

The controversial Gallipoli landings were a daring – or foolhardy – attempt to break the stalemate on the Western Front by attacking Germany’s ‘soft underbelly’ through her Ottoman ally. The campaign, blighted by poor planning and lack of intelligence, was to prove ultimately disastrous for the allies, and the whole thing was called off by January 1916.

After her return from the Mediterranean, M33 had a chequered history; after supporting the White Russians against the communists at Murmansk in 1919, she became variously a mine layer, fuel transport and floating workshop, before being laid off by the Navy, acquired by Hampshire County Council and put into dry dock at Portsmouth.

As with HMS Caroline, these changes in function were accompanied by changes of structure and appearance. Since the late 1990s she has been painstakingly restored – with a new mast, funnel and guns cannibalised from various dockyards around the world. In 2007, she underwent her most noticeable transformation back to her First World War form when she was repainted in dazzle camouflage.

HMS Monitor M33 in 2010, courtesy of Wikipedia

Any similarity between dazzle camouflage – with its strikingly contrasting geometric patterns – and contemporary modernist art was not entirely accidental; it was invented by the English Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth.

Unlike most normal forms of camouflage, the effect of dazzle was not to conceal but to confuse, with strongly broken outlines making it difficult for the enemy – particularly those with their eyes to a periscope – accurately to plot a vessel’s direction and speed.

The USS West Mahomet (public domain)

The USS West Mahomet (public domain)

A further round of funding from the HLF announced in September 2013 will see the interior refurbished and opened to the public for the first time.

Unlike the Caroline, it seems HMS M33 will be less of a floating museum and more of a historical re-creation, allowing visitors to experience a First World War ship as she would have been at the time, and adding to Portsmouth’s already impressive collection of historical vessels.

HMS President

HMS President has a very different livery from the M33. Moored in the River Thames at Blackfriars in London, she is a familiar (and deceptively innocuous) sight for many of us. Greatly transformed throughout the later 20th Century to adapt to changing roles, she is hard to recognise as a combat vessel. In fact, few would have recognised her as such in 1918, when she was launched as an Anchusa-class sloop – her deceptive appearance was the name of the game. She was a Q-ship.

After Jutland, the German surface fleet was largely confined to port. However, many in the German Navy were still keen to use their resources against the British war effort. Submarines seemed the obvious answer as, while submerged at least, they remained almost undetectable to the powerful British warships.

It was not warships, though, but merchant vessels that were the prize targets. As Britain continued to blockade Germany by sea, so Germany sought to blockade Britain from under the sea. Indeed, if the U-boats had continued to sink allied shipping at the rate they achieved in April 1917, they would almost certainly have won the war. The British, growing seriously concerned by mounting losses, came up with increasingly inventive countermeasures.

One such was the Q-Ship. Designed to appear as defenceless merchant vessels, they were small enough to encourage a U-boat captain to surface and attack with his gun, sparing his costly and limited torpedoes for more profitable targets. Coming under attack, the prey would then open fire with cleverly concealed weaponry, often able to outgun a submarine by a ratio of 3:1. If the hunter-turned hunted was able to submerge and make a run for it before sustaining too much damage, the Q-ship would then be able to give chase and attack with depth charges.

HMS President, courtesy of Wikipedia

HMS President, courtesy of Wikipedia

Ultimately, it would be the development of the convoy system and aircraft that would put an end to the German U-Boat campaign. Enough supplies made their way to Britain to keep her in the war, and Germany made few friends by targeting merchant vessels of neutral nations – arguably, it was the key factor in precipitating American entry into the war.

Like HMS Caroline, the President acted as a training ship for many years. In the 1980s, she passed into private ownership, and is now used as an office and hospitality space. Although plans have not yet been released, the owner intends to use the ship as a historical resource during the Centenary period. While she bears little resemblance to her original form, the President still maintains a physical link to a period of the war that saw the British, through desperation, becoming masters of deception and invention.

HMS President is currently open to visitors by appointment only. HMS M33, located at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, is due to open in time for the centenary of the Gallipoli campaign in 2015, and work on HMS Caroline, at Alexandra Dock, Belfast, is hoped to be completed in time for the centenary of the Battle of Jutland in 2016.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author