Missing fragments from a Great War masterpiece are back on display for the first time in decades at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. CN contributor Patrick Gregory retraces the truncated history of ‘Panthéon de la Guerre’, the world’s largest painting when it was first unveiled in Paris in 1918.

When one is asked to think of famous depictions of war or of military figures – whether the subjects are the victors or the vanquished – the mind might turn towards those horrors conjured up by Goya in Napoleon’s Iberian campaign or the modernist straining sinews of man and beast in Picasso’s Guernica. Or perhaps the more dignified and heroic deaths of military leaders like Benjamin West’s Death of General Wolfe or the various patriotic images of Nelson’s last moments in the 19th century.

But there is one giant of 20th century military art which is being gently reawakened in America’s Midwest in advance of the United States’ WWI Centennial in just over a year’s time. The giant isn’t all he once was, but he’s gradually regaining some of his strength.

When it was finally finished in France in the autumn of 1918 – the work of 128 artists over a four-year period – the Panthéon de la Guerre was a monumental piece of work in all senses. A vast cyclorama of famous figures from the Great War, it boasted a 402 feet circumference and stood some 45 feet in height.

“It’s challenging to put in perspective how massive this painting was in its original form,” says Doran Cart, Senior Curator at the National World I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. “Imagine a canvas longer than a football or soccer field – it was simply colossal in size and scope.”

The painting encompassed 6,000-odd figures drawn from Allied nations on the Western and Eastern Fronts as well as the Balkans, the Far East, North Africa and Latin America.

However the significance of this work arguably rests as much on the history of what happened after it was unveiled – its backstory and the picture it gives us of art curation and of Franco-American relations in 20th century – as on its epic size or who featured in its original form. This latter story is the tale of two men in particular, the American artist Daniel MacMorris and a Baltimore restaurateur called William Henry Haussner.

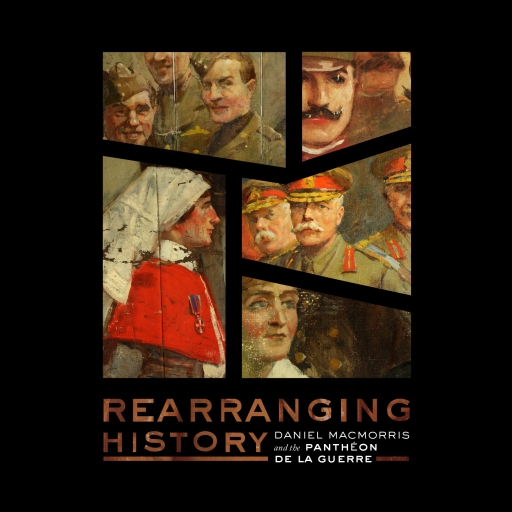

A British nursing sister from ‘Panthéon de la Guerre’ (Image: National World War I Museum and Memorial)

A British nursing sister from ‘Panthéon de la Guerre’ (Image: National World War I Museum and Memorial)

For his part, Daniel MacMorris had spent different periods of his life in France: in the inter-war years as an artist, and as a soldier during both World Wars. But it was during his time in Paris in the 1920s that his interest in Panthéon first began. He had worked as a student under Auguste François-Marie Gorguet, one of two co-ordinators (with Pierre Carrier-Belleuse) of the painting, and had studied the vast canvas of figures depicted on the sprawling landscape of the First World War’s battlefields.

Many more joined him in admiring the craftsmanship of the giant artwork – it was visited by an estimated 8 million people in the years 1918 to 1927 – but it was in that year that it was acquired by a group of American businessmen and taken to New York.

It was displayed at Madison Square Garden and some small changes were made to make the work more attractive to a US audience: Colonel Edward House, Woodrow Wilson’s wartime foreign policy adviser was painted out, for instance, and replaced by the influential early wartime American ambassador to France, Myron T. Herrick. The painting then went on to tour the United States at a series of exhibitions and expos.

But time and interest gradually passed and the painting ended up being placed into storage in 1940. It was eventually rediscovered and rescued in 1953, acquired at auction by William Haussner for $3,400. MacMorris learned of its existence – its return from obscurity – reading about the auction in a Life magazine article, and he and Haussner began corresponding.

By this time MacMorris was working on a project to decorate Liberty Hall in Kansas City, Missouri and after some more years’ discussion between the two it was decided that Haussner would donate the picture to the Hall, to be adapted for the one remaining wall there.

‘Whittled down’

MacMorris now began to photograph the old painting in detail. He cut out the figures in the photographs he had taken and used them like pieces of a giant jigsaw: to work out how best to reduce and reconfigure the composition to fit the new space, an effort he compared to ‘whittling down a novel to Reader’s Digest condensation’.

After deciding whom to include and where to place them, he took scissors to the canvas itself. He cut out selected figures, flags, and other passages and added these to either side of the original American section. Allied leaders and military figures from Europe still featured, but to their midst were added later American figures like Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, a First World War veteran and native of Missouri. Colonel House was now rehabilitated and portraits of the artists Gorguet and Carrier-Belleuse included.

But what happened to the unused portions of the original? By far most of what MacMorris did not use he threw away. He sent several larger, excised passages back to Haussner, who displayed many of these in his eponymous restaurant until it closed in 1999. MacMorris doled out other pieces to the art students who helped him reconfigure the painting. Still others he gave to influential Kansas City residents.

Now that original jigsaw, first seen in France in 1918 and last seen in its full glory in America in 1940, is as complete again as it can be. The National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City has collected as many of the remaining and available figures and fragments together as possible, to mount the largest exhibition of the Panthéon since its last complete exhibition 75 years ago. History reimagined.

‘Rearranging History: Daniel MacMorris and the Panthéon de la Guerre’ is open at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, until 27th March 2016.

Images courtesy of National World I Museum and Memorial

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber’ – to be published by The History Press in June 2016