Heather Payton writes for Centenary News about an extraordinary example of cooperation between British and German troops, uncovered by research for a forthcoming First World War Centenary exhibition in Wales.

Members of the Local History Society at Llangwm in Pembrokeshire have been poring over log books and diaries kept by a young pilot from Cilgerran, and they reveal the camaraderie that sometimes took precedence over hostilities, certainly in the war in the air.

Excerpts from the diary, together with photographs, will be on show at the Heritage Lottery funded exhibition, in Llangwm in November 2014.

The pilot, William David Sambrook of the Royal Naval Air Service, was posted to Coudekerque airfield near Calais in 1916, one of many allied and German airfields in that part of France and Belgium. He was 22.

David Sambrook and a fellow airman, titled as ‘Lipton and self’ in his album (courtesy of Richard Palmer)

Sambrook’s diaries tell of almost daily bombing raids on German-held aerodromes as well as the docks and Zeppelin sheds at Bruges and Zeebrugge.

But one day in May 1916, one of their number failed to return from a raid on Ostend aerodrome, and there was talk of his aircraft being picked up from the sea by a Belgian trawler.

Missing

A few days later, with still no news of the missing man, one of Sambrook’s colleagues flew over the German airfield and dropped a message asking if they had information about his fate. The British pilots received a prompt reply, also dropped from the air, confirming that the aircraft had indeed been shot down over the sea.

Sambrook takes up the story in his diary: “They said attempts had been made at rescue but when the machine was brought in the pilot was already dead.

“He was buried with full military honours alongside two comrades at Marrakerke cemetery, Ostend. The message was accompanied by two photos of the funeral and the grave.”

Examples had been noted before of each side treating the bodies of their victims with respect, but a postscript to the note shows an unusual degree of fellow feeling among pilots.

“There was also a message in German stating the name and place in German territory where our machines could land if they had engine trouble.”

Cooperation

So how common was this degree of cooperation? Alan Wakefield, head of photographs at the Imperial War Museum, says it was much more common among pilots than among those fighting the war on the ground, where the conflict soon became impersonal.

“I know of cases where German pilots dropped notes and photographs of a crashed aircraft and its occupant, saying they’d buried him and asking for his name so they could make a headstone.

“In fact in one instance a German pilot dropped a note saying he was about to bomb an airfield and suggesting that those on the ground should get out of the way”.

But Wakefield is sceptical about the tip-off giving details of a safe landing place.

“This is surprising because the German squadron would not have had jurisdiction – the German army were under instruction to take British pilots prisoner.

“I think it’s more likely to have been an example of German humour – they wouldn’t have expected the British to take them up on it.”

‘Deck Flying’

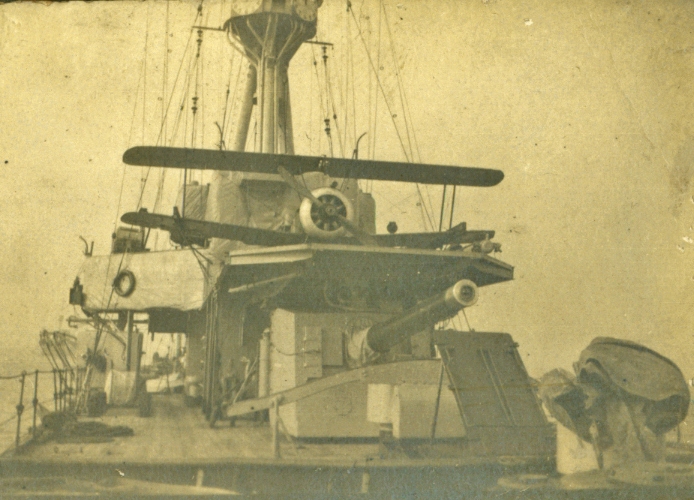

David Sambrook’s Sopwith Camel, on board the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney (courtesy of Richard Palmer)

Towards the end of the war, Sambrook went on to become one of the first pilots to engage in ‘deck flying’, taking off in Sopwith Pups and Camels from short platforms built on gun turrets, on what were to be the forerunners of aircraft carriers.

He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for gallantry in the air in 1917.

Sambrook survived his time in France and after a career working in the public health department of Westminster City Council, he returned to Pembrokeshire to live with his sister in Deerland, Llangwm.

His nephew, Richard Palmer, still lives in the same house and has kept his diaries and logbooks safe.

“He was a lovely man” Richard said. “When he was in London he would send us Twickenham rugby match programmes and he kept brother Maurice and myself supplied with rugby boots.

“But he never spoke to us about his war record.”

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author