Dr Jillian Davidson attended the “Perspectives on the Great War” conference in August 2014 – and sent this report.

“Perspectives on the Great War” was an international and interdisciplinary conference held at Queen Mary, University of London, to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. According to the conference’s organizer, Professor Felicity Rash, from the School of Languages, Linguistics and Film, the purpose was both academic and commemorative: “while participants will be constantly aware of the devastation of this dark period in world history, the organizers hope that they will also enjoy it as a landmark in scholarly collaboration and world-wide friendship.”

Of the 140 papers and 10 keynote lectures delivered from August 1st through 4th 2014, several belonged to the discipline of academic studies, several to the discipline of memory studies and several to the discipline of international relations, but most belonged to more than one of these disciplines. Thus, even though sessions were arranged thematically, addressing perspectives from a variety of vantages – political, colonial, military or naval, cultural, morale and religious – many papers encompassed more than one of these.

Santanu Das, for example, from King’s College, London, spoke of “The Singing Sepoys: encounter, ethnology and music in a German POW camp.” His paper examined the relationship between ethnology, colonialism and the history of emotions by looking at an extraordinary series of encounters between Indian sepoys and German academics in two POW camps outside Berlin.

Education naturally lies at the nexus where academic and memory studies meet. Amy Carney from Pennsylvania State University presented the parameters of a Paris Peace Conference role playing game which was developed for a college-level modern western civilization course in her paper on “The Behrend College Gaming the Great War: the student perspective of the Paris Peace Conference.”

The conference accordingly succeeded in meeting its main aim to be multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary. As one delegate commented, illustrating the consensus of the attendees: “It was very exciting to get a full overview about the current state of research in First World War studies in all its diversity. I particularly enjoyed the opportunity to discuss with colleagues from outside Europe, which is unfortunately not very often the case.”

Commemorating the summer of 1914

Seizing upon the significance of the day, Samuel R. Williamson, from The University of the South, in his keynote lecture on Sunday afternoon of August 3rd, began: “Today, one hundred years ago on this afternoon, Sir Edward Grey addressed the House of Commons. In an historic speech that sought to explain why Britain might have to go to war, Grey was at once honest, deceitful, patriotic, candid about entente obligations to France, and careful to omit any reference to Russia. Above all, he sought to explain how Britain might become involved in a Continental quarrel that had started just five weeks before with two murders in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo.”

The buzzword of Williamson’s talk was “miscalculation.” A series of miscalculations in the summer of 1914 linked his narrative. Fewer than a hundred men made the decisions that led Europe to war. “Each made miscalculations or participated in errors of judgment or assessment.” Of those men and their “depressing” miscalculations, no one played a more crucial role than the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister Count Leopold Berchtold.

Berchtold “made the most fundamental miscalculation of all the leaders in 1914.” He never calculated that Russia would intervene militarily in a local war of Austria-Hungary against Serbia. His lack of understanding in the Balkanization of Russian policy was due greatly to the fact that there had been no Austrian ambassador in Russia since autumn 1913. He also miscalculated that Austria-Hungary could launch a quick war against Serbia. Upon receiving the “blank check” support from Germany on July 5 and 6, he was informed by Army Chief of Staff, General Conrad, that much of his army was on “harvest leave.”

Berchtold’s most pivotal miscalculation, however, was that he did not anticipate a conflict of interests with the Hungarian Prime Minister, Istvan Tisza. Consumed by his struggle with Tisza, Berchtold had no time to reconsider his own policy plan.

Williamson concluded: “We should end as we began. By now, on August 3, Grey might have finished his long speech. Later that evening, with the prospect of war certain, he uttered to John Alfred Spender, editor of the Westminster Gazette, the famous lines: ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’” Each government had miscalculated in 1914 and as perhaps the most sober lesson of the war’s origins, governments continue to do so, a century later.

A new generation of “transnational” historians

Jay Winter, in his keynote address, contextualized this generation’s writing on the Great War, the fourth generation to date. The first generation of writers comprised of “the Great War generation,” those who had direct knowledge. Winter’s second generation wrote “fifty years on” and his third was the “Vietnam generation.” “Now we are in a fourth generation,” he declared, one that he likes to term the “transnational generation.”

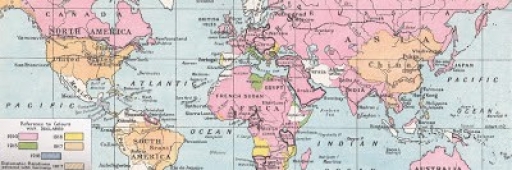

In contrast to an international approach, “Transnational history does not start with one state and move on to others, but takes multiple levels of historical experience as given, levels which are both below and above the national level.” Comparative urban and rural studies; the history of women in wartime; the history of mutiny and revolt; the study of finance, technology, economy, logistics and command; and the history of commemoration are all transnational. The icon of transnational history in the twentieth century is the refugee, with his or her belongings slung over a shoulder or cart.

War, according to Jay Winter, is such a protean event, touching every facet of human life, and this was amply reflected upon at the Queen Mary Conference. Historically, migrant musicians have provided some of the most outstanding benefits of a transnational network and the Queen Mary conference succeeded in delivering on this front too. To mark the centenary, the conference included as part of its programme a concert that celebrated transcultural compositions by Arthur Sullivan, George Dyson and Sigfrid Karg-Elert. The interruption and loss of centuries of fertile musical exchange between Britain and Germany has been one of the least appreciated legacies of the Great War.