The number of soldiers killed or who died on active service in the Great War has been massively underestimated, according to a new book.

Antoine Prost, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Paris, reveals the discrepancies in an essay for The Cambridge History of the First World War, which was published on 23rd January 2014.

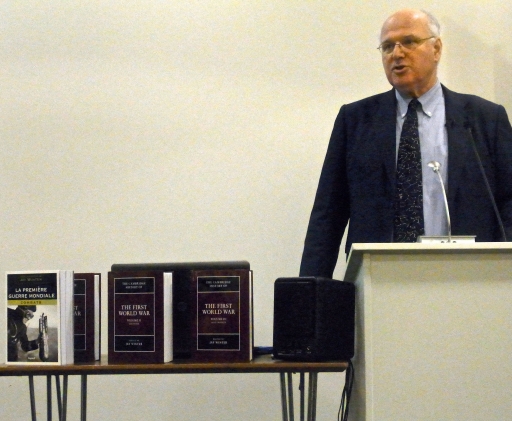

His conclusions are among the “striking findings” to emerge from the contributions of the world’s leading historians, says Jay Winter, Editor of the three-volume series and Professor of History at Yale University in the United States.

The number of men who suffered shell shock is also said to have been much underestimated.

Professor Prost, in his essay entitled ‘The Dead’, puts a figure of over ten million on the overall number of First World War military casualties, half a million more than the most recent estimates.

Errors

Examining estimated losses among all the combatants, he discovered dozens of errors and miscalculated figures. Many of these resulted from administrative confusion, but taken together, Professor Prost says they indicate a tendency for all sides to minimise their losses: “The calculation of military losses isn’t easy and most studies present lists of figures without explaining what they cover or how they have been established.

“So there is confusion concerning places whose borders had shifted; there is inconsistency in recording the deaths of soldiers from sickness and prisoners of war who died in captivity; and there is uncertainty surrounding the number of soldiers reported missing.

“Overall it means a complex network of dispositions of individual soldiers wounded, killed or missing underlay the evolution of statistics of war-related casualties and it thus seems that in several cases, including Britain, the generally accepted calculations are underestimates.”

Launching the Cambridge History with a lecture at the Imperial War Museum in London, Jay Winter forecast that some of the book’s other conclusions would also spark vigorous debate: “Every one of the chapters has innovative things to say,” he declared.

He himself argues that cases of shell shock have been “vastly” underestimated, saying he now believes more than 20 per cent of men suffered from the condition. Earlier calculations ranged between two and four per cent. That would mean more than 500,000 cases in Britain alone, and over five million worldwide.

Professor Winter said: “We can understand how many families were blighted by it. Families for which the men were not recognised as having even this type of injury. The history of family is central to this story too.”

Medical and administrative practices of the time, as well as prejudice, are all blamed for the reluctance to diagnose many injuries as psychological.

Professor Winter points out that doing so would probably have made it less likely that a disabled man would receive a pension. But he says it “makes no sense at all” that even soldiers with physical wounds, such as loss of limbs or facial disfigurement, were rarely, if ever, deemed to have additional psychological injuries.

And he had this challenge for his fellow historians: “If we don’t even know how many people died in the First World, we’ve still got some research to do.”

*The Cambridge History of the First World War, published by Cambridge University Press, is described as the first ever transnational account of the conflict. It is edited by Jay Winter and the Editorial Committee of the International Research Centre at the Historial de la Grande Guerre museum, located at Péronne on the battlefields of the Somme.

A French translation is being simultaneously published in France by Éditions Fayard.

Source: Cambridge University Press; lecture at IWM London, 23rd January 2014.

Images courtesy of Cambridge University Press and Peter Alhadeff, Centenary News

Posted by: Peter Alhadeff, Centenary News