This article has been written by Centenary News volunteer writer Katherine Quinlan-Flatter. She visited the Belgian city of Kortrijk for an exhibition at the heritage museum Kortrijk 1302, exploring the German occupation of 1914-1918.

The World War I exhibition at the heritage museum Kortrijk 1302 examines an aspect of the war rarely touched on in other current exhibitions – the German occupation during the war years. Belgium was invaded on August 4, 1914 by Germany, which did not recognise Belgium’s neutrality.

Kortrijk itself was taken on October 17 and became known as “Etappengebiet” – a region supplying and supporting the army at the Front. All manner of goods and food supplies were immediately requisitioned for the Germany army and what remained for the Belgian people was rationed.

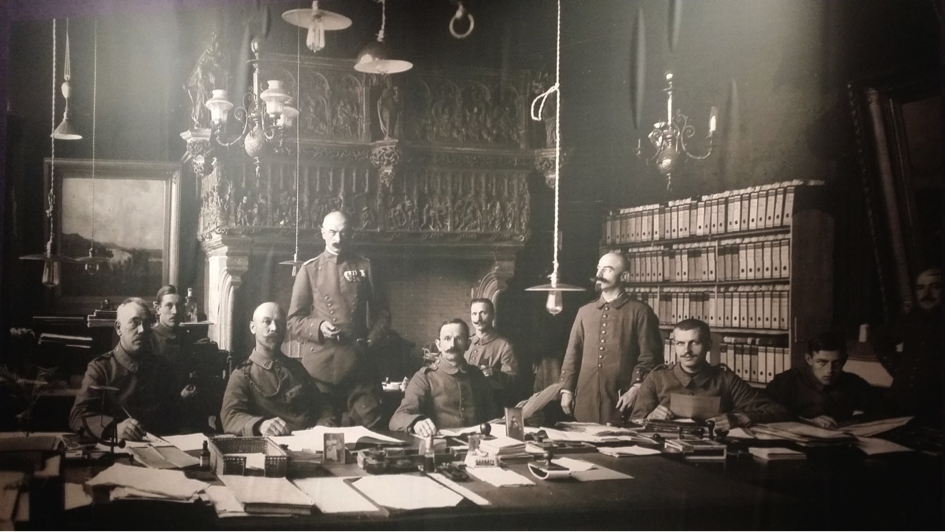

The Kortrijk city council was replaced by nine German commanders known as “Etappenkommandanten”. These commanders set up their own administration system in confiscated public buildings, schools, convents and private houses, and introduced a new system of identity cards and passports.

The Etappenkommandanten (Photo copyright ©Stad Kortrijk)

Various Belgian citizens worked as spies for the Resistance, passing on information to the Allies via a network. Some, however, joined the activists striving for independence from Flanders and cooperated with the German occupiers, leading to political tension in the city. On the whole however, the residents remained patriotic – although while the French-speaking bourgeoisie was largely able to rely on its own reserves, many poor people went hungry and cold.

Kortrijk 1302’s exhibition “Kortrijk Beset 14-18”, which will run until June 2016, has the leitmotiv “On the trail of a spy”. The lower floor covers the year 1914-1916, at the start of the occupation, while the upper floor continues with 1917-1918.

One day’s march from the Front, the town was an important point of supply for the German troops, and held several lazarets for the wounded, converted from schools, monasteries, colleges and hospitals, while spies lurked in every corner.

Spying

One such spy, Evariste De Geyter, whose life-size photo appears at various points in the exhibition, worked at the railway station, responsible for one of the tracks. This was a position of prime importance as the Germans used the railways for their manoeuvres and logistics. Living next to the station and noting all movements on the railways, he was able to pass on information to the Allies, who used it to predict attacks.

The individual rooms of the exhibition are dedicated to various aspects of the occupation and the excellent and varied presentation methods ensure that the visitor is fascinated and captivated from start to finish. Apart from the usual displays of objects in glass cabinets, each room contains moving film, touch screens, audio recordings and life-size photos – often with actors performing the role of a highlighted persona.

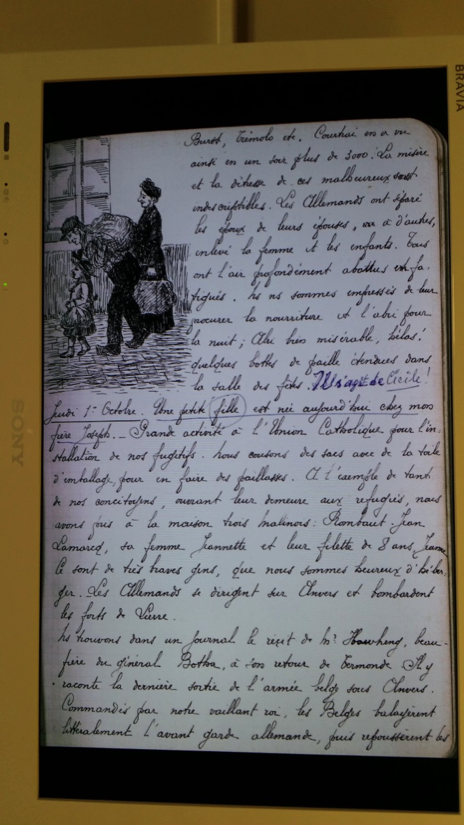

Marguerite Ghyoot of the bourgeoisie wrote a diary in French, extracts of which are shown on a large touch screen, together with some of her jewellery. Opposite her in the same room, the less fortunate Madeleine Pollefeys – whose husband was requisitioned to work for the Germans – is depicted. Many of the requisitioned workers were sent to work camps, where conditions were worse than in the town itself, but propaganda photos on the walls of the room display them as happy and content.

Extract from Marguerite Ghyoot’s diary (Photo copyright ©Stad Kortrijk)

A wall-sized photo of the German troops marching into Kortrijk shows the assembled Belgian citizens as curious and apprehensive – the last war known to the population was the Belgian Revolution of 1830. When the German invasion resulted in shortages for the citizens of Kortrijk, the USA and Spain sent help in the form of war money, which, it was agreed with the Germans, would be distributed directly to the population. Coupons for food and coal, for example, are also on display.

Upstairs, one room is dedicated to the German administration machinery. Bureaucratic books, newspapers and typewriters cover the tables in the centre of the room to recreate the original atmosphere, as in every room. One wall depicts an almost life-sized photo of the German commanders in a regally decorated study. A mirror image on the opposite wall shows a black and white film of the recreated study with a German actor dressed as a commandant, speaking directly to the camera.

Pigeons

Another room depicts how the Germans lived in Kortrijk before and after their deployment at the Front. One wall is covered with an endless series of “Bekanntmachungen” (announcements). The population was prohibited from almost any kind of activity without German approval. Even pigeons were requisitioned and the Germans maintained a prison for them. The original pigeon carrier baskets are on display in the centre of the room.

Rittmeister Albrecht von Richthofen was one of the Etappenkommandanten, and in 1917-1918 held the position of Ortskommandant. His son Manfred, the famous flying ace, was the popular leader of a squadron of pilots. The von Richthofens lived on the outskirts of Kortrijk in Marke Castle, about 25 km from the Front.

Manfred was shot down on July 6, 1917 in his Albatross bi-plane, wounded to the head and treated in a lazaret in Kortrijk. The Fokker tri-plane was subsequently introduced by Anthony Fokker, and, against the advice of doctors, Manfred flew the Fokker for about a year. He was shot down and killed in 1918 in France.

Manfred von Richthofen with his squadron (Photo copyright ©Stad Kortrijk)

A large photo of Manfred von Richthofen and his squadron on the steps of Castle Marke is shown in a room which resounds with an audio recording of the noise of bombing and planes flying over the city. Many civilians also died in the bombing and as a result of the occupation. The Germans built several airports around Kortrijk and beyond. Both the Kaiser and Ludendorff visited the pilots at Kortrijk, flying across the Front and taking photos of the Allied positions, which are shown in this room. The room also contains equipment to send signals to pilots, a signal lamp, a trench periscope and a large mobile phone.

A short film of the von Richthofens, Marke Castle and Manfred flying his Fokker plays on one of the walls. The original film is owned by Steven Spielberg (a fan), but the museum holds this copy.

The last room depicts the liberation of Kortrijk by the British in October 1918, the British teaming together with civilians in photos loaned by the Imperial War Museum in London. Finally, the story of the spy is taken up again. De Geyter received information that the area in which his house was located was to be bombed, but he remained so as not to arouse suspicion. His daughter, however, was later killed in a bombing raid. De Geyter was ultimately caught and tried, but unlike other spies was not executed because of the death of his daughter. He survived the war, subsequently writing his memoirs and receiving medals for his bravery and services.

More information about the exhibition ‘Kortrijk Bezet 14-18’ can be found here

All images copyright ©Stad Kortrijk

Article: ©Centenary News & Author