Washington Art historian Mark Levitch has embarked on an ambitious Memorial Inventory Project to uncover the 10,000 or more American World War One memorials scattered across the country.

Here, he tells Mike Swain, at Centenary News of some of the amazing monuments he has discovered and what they tell us about America 100 years ago and today.

Mark, how did you get the idea for the project?

I was researching a fascinating-sounding WW1 memorial that the French reportedly had donated to the US in the late 1920s that contained earth from all of the battlefields where the Americans had fought.

Several French sources indicated the memorial was at Arlington Cemetery, and I figured it would be pretty easy to track down. But I could never find it – and in fact I still haven’t.

Soon after that, I was in the Berkshires (western Massachusetts) for a couple of weeks for summer holiday with my family. We rented a house in a tiny, rural community, and I was surprised to see a small World War One memorial situated at the town’s main intersection.

I started paying attention as we drove around the region and soon realised that nearly every community had a memorial, and that larger towns and cities often had elaborate sculptural or architectural memorials.

A little research turned up that we weren’t too far from the state’s official WW1 memorial, which sits atop Mount Greylock, the highest peak in the state, near where three states border one another.

Memorial at Mount Greylock. © Mark Levitch.

And it is truly impressive, a real wonder – shaped like a lighthouse and topped by a beacon visible from 70 miles away. But it was also in pretty poor condition – there was significant water damage and its solemn entry chamber had been vandalised. (It is now closed and slated for repairs.)

I must have come across 30 or so memorials in those couple of weeks – most erected by towns, but also by high schools, universities, businesses, and churches, and I found the sheer number and the different forms they took quite interesting – and the physical condition of more than a few of them rather distressing. And since then I’ve had the bug.

How did you set out to organise it?

It’s still very much a work in progress. I started poking around on the internet to see what sort of lists, inventories, and databases were out there, especially related to public art and war monuments.

Mark Levitch

I found a few good examples, including a mammoth survey of outdoor sculpture undertaken in the US in the late 1990s (which includes hundreds of WWI memorial sculptures).

UK model

But by the far the most apposite example seemed to be the UK National Inventory of War Memorials (now known as the IWM’s War Memorials Archive).

And when I was in London in 2009 for the First World War Studies Association conference, I went and met the staff, who were kind enough to take a couple of hours to discuss how they were organised and precisely what information they sought from the public. And the framework for the US inventory really is based in large part on the UK model.

I am now working with the US WWI Centennial Commission on setting up the database, probably on their site. I’m also coordinating with a more hands-on conservation non-profit, Saving Hallowed Ground, which aims to get students involved in conserving and researching local memorials.

I also plan on contacting the 50 State Historic Preservation offices with the hope that they can help promote the project.

What has been the response and where has it come from?

The response has been great. I’ve been contacted by people from every region of the country. Most want to report a single memorial with which they’re familiar.

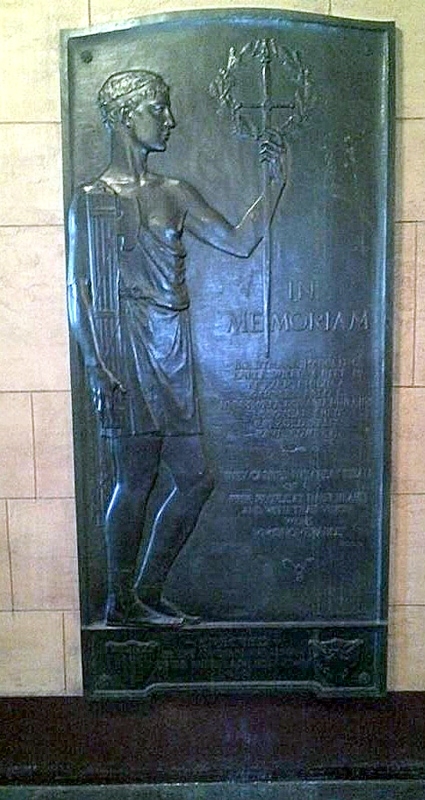

White Plains school memorial. © Angel O’Hanlon Tinnirello

This is how I learned, for instance, about a great memorial relief in the foyer of a school in White Plains, New York. And the Mayor of Tyrone, Pennsylvania, contacted me about the town’s doughboy memorial, of which Tyrone is rightly proud.

Tyrone’s Doughboy memorial. © Bob Dollar

Many people remember memorials from their childhood. It’s quite touching to talk to a senior citizen about a hometown sculpture that has remained so important that he or she recalls it in detail – and with pride — decades after moving away.

Tell me about the variety of monuments. What kind of things were erected?

The variety of monuments is staggering – it’s really one of the most surprising and intriguing aspects of this project.

There was a vigorous debate in the US after the war about what constituted an appropriate memorial – something traditional that invited contemplation or something useful or functional that would tangibly benefit society. In the end, we have both in huge numbers.

There are beautiful and moving memorials by the leading sculptors of the day, such as Daniel Chester French; paintings, murals, and stained glass by some of the foremost painters, including John Singer Sargent and Grant Wood; and grandiose war memorial buildings – such as Kansas City’s Liberty Memorial and San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House, among many others – designed by the country’s best-known architects.

San Francisco Opera House. © Mark Levitch.

And then there is also this hodgepodge of utilitarian memorials – bridges, roads, hospitals, libraries, stadiums, community buildings, schools, etc.

There are also hundreds of mass-produced doughboy sculptures, the most common being E.M. Viquesney’s Spirit of the American Doughboy; there are about 140 examples across the country.

I’m especially interested in the memorials that have a distinctly local flavour.

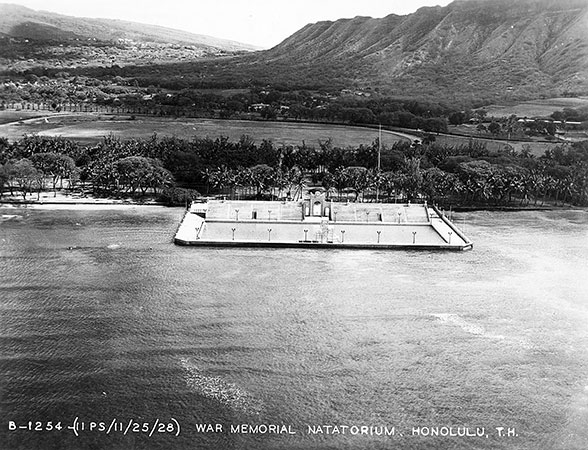

Waikiki Natatorium swimming pool. Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives.

These include the Waikiki Natatorium War memorial, an ocean-water swimming pool that is Hawaii’s official memorial (and which, unfortunately, is faced with demolition); a series of memorial buildings in California designed in Spanish colonial style; and several sculptures or small structures that have a folk-art quality.

Many memorials also reflect a given community’s particular war service. My favourite of this genre is at Smith College, a women’s college in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College. © Mark Levitch

They recreated the entry gate of the chateau in Grécourt, France, where the Smith College Relief Unit was based during and after the war.

There are oddities, too, the best-known being a privately sponsored World War One memorial in Maryhill, Washington, which features a full-sized recreation in cement of Stonehenge.

Tell me some anecdotes of things you have found.

One of my most gratifying journeys was a day trip to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, which is the state capital. My primary goal was to see and photograph a massive memorial bridge that was erected in 1930. I had seen photos of the bridge, the western end of which has two massive pylons, each 145-feet-high and topped by art deco eagles.

Harrisburg PA Soldiers’and Sailors’ Memorial Bridge. Public Domain.

But I was unaware of the fabulous keystones – stylised representations of World War One weaponry — that adorn each of its 17 arches.

Not all of them were accessible, but with a little climbing and ingenuity – including avoiding a rather aggressive hedgehog who had made his home in an adjacent rundown lot — my daughter and I were able to at least glimpse most of them.

Statue of fireman at Harrisburg Bridge. © Mark Levitch

We then went in search of a doughboy statue that I had read was near the riverfront. We found it pretty easily, and then I noticed nearby a sculpture of a fireman. We went to take a look, and I was surprised to see that it was a memorial to the Harrisburg firemen who had perished in World War One.

Then, on our drive out of town, we spotted another monument, and it turned out to be an elaborate bronze relief dedicated to the “services and sacrifices of Harrisburg women” during the war.

Memorial to the sacrifices of women in World War One. Harrisburg PA © Mark Levitch

I think it’s pretty amazing that these four significant World War One memorials – state and privately sponsored and dedicated to such different aspects of the war experience – have such a prominent place in the city’s landscape.

And at the same time it’s sad to think that they – and the history that gave rise to them – are generally forgotten. My hope is that the inventory project, by locating and telling the stories of these memorials, can help recover this history and again make it, and the memorials, vital.

Has your perception about how people felt about the war been changed in any way?

Almost from the beginning, I’ve been struck by the time, dedication, and money that went into commemorating the war across the country at all levels of society.

Obsession may not be quite right, but the determination to memorialise the war’s participants was ubiquitous and a significant element of inter-war culture. And I’m constantly surprised by the disparate forms that the memorials assumed.

What is the level of interest in the USA today in the Centenary?

US interest in the Centenary is nothing like it is in Europe. But we do now have a congressionally mandated US WWI Centennial Commission, which is working tirelessly to increase awareness about the anniversary.

In June, for instance, the Commission is sponsoring a convention in Washington, DC, to gather together the various organisations with an interest in the war.

Unfortunately, the Commission was not given any appropriated funds, so it has to raise money itself. It is likely the country will focus most of its attention to the centennial in 2017, the anniversary of US entry in the conflict.

National World War One memorial in Kansas City – the grandest of tributes.

I am hopeful that the Centennial and its expected attendant programming – exhibitions, books, conferences, radio, TV, film (and even the memorial inventory) – will attract new interest in the conflict. The country also has a superb, and still fairly new, National World War I Museum in Kansas City (located at the Liberty Memorial, which is doubtless the grandest of the country’s World War One memorials – a story in itself), and I think anyone who sees that comes away with an abiding appreciation of the war’s import.

Can you explain the importance of World War One to America?

I don’t think there is an aspect of American society that was unchanged by the war. To begin with, it marked the ushering of the US onto the world stage and the start of the so-called American century.

Washington DC First Division monument. A collaboration between leading architect Cass Gilbert and sculptor Daniel Chester French. © Mark Levitch

It catalysed US economic might, forged the US army of the twentieth century, and led to the vast expansion of the US government.

Socially, it led to an expanded role for women and the right to vote; encouraged the Americanisation of immigrants; and kicked off the Great Migration of African Americans.

And culturally, it was the touchstone for modern American literature. The US, too, like other countries, continues to face international crises with their roots in the war and its aftermath.

How should people go about finding out if their area has a WW1 monument?

The first recourse is simply to look around. Many towns have memorial buildings that were erected after the war in memory of those who were killed.

Smaller communities often have bronze honour rolls – sometimes in city hall, in the courthouse, or affixed to a stone somewhere in the centre of town (such as a town green), or in a park.

Commemorative sculptures, too, are usually located in prominent sites. Older churches, synagogues, high schools, and sizable businesses (such as factories) also frequently erected honour rolls, and finding those requires legwork.

Emmitsburg, Maryland. Viquesney Spirit of the American Ploughboy.

Local historical societies and public libraries are invaluable resources; they often have memorial dedication programmes or other pertinent archival material.

There is also a plethora of material on the internet. The Smithsonian’s inventory of American sculpture, waymarking.com, and the historical marker database all list World War One memorials. The internet archive and Google Books also are rich veins for online research of the post-WWI period.

How is the project organised and supported?

The project has been incorporated as a non-profit entity, so individual contributions are generally tax-deductible.

This non-profit status also allows us to apply for grants. It is still essentially a one-person operation in terms of time and funding, though I am grateful to have received contributions from friends, relatives, colleagues, and a few people who have learned about the project and deemed it worthy of their support.

How can people get involved?

Anyone who wants to help out – either by supplying information about a memorial or administratively – can contact me via our website (http://wwi-inventory.org/) or via our Facebook page (www.facebook.com/wwiinventory), where I often feature memorials submitted by volunteers.

At the end of the project what will you hope to have achieved?

I’m not really sure there will ever be an end to the project, but I hope the process of compiling the inventory will bring the memorials – and the war – into the light, so to speak.

I hope it will inspire people to revive and reclaim their local memorials; to delve into the memorials’ histories – including the stories of those listed on a given memorial; and to think about how to ensure the memorials’ ongoing conservation and long-term preservation (for instance, by applying for landmark status).

I also want the inventory to be an academic resource – an exemplar, I hope, of public history that will contain both short interpretive essays (dealing with specific memorials or memorial-related issues) and the data necessary for a scholarly analysis of the corpus of memorials (or of a specific subset).

Posted by Mike Swain