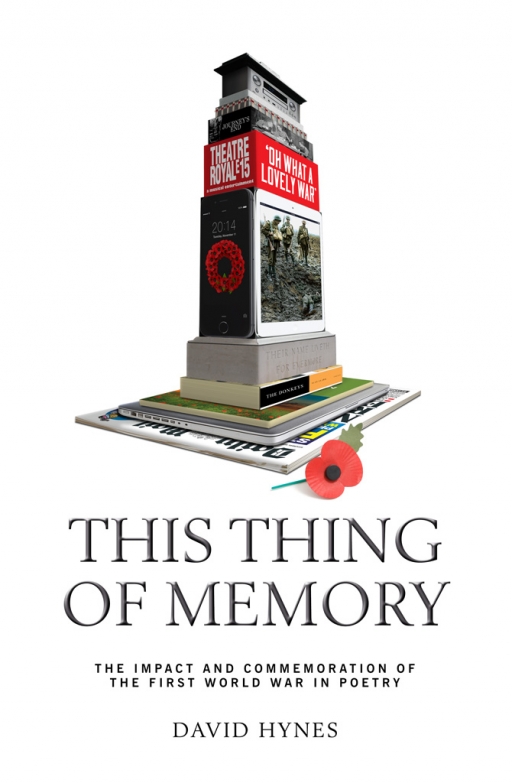

This Thing of Memory is a new volume of poems by David Hynes, examining the impact of the First World War; its imprint on our memory and conscience, both personal and collective, and the experience of the centenary commemorations: a unique event for each generation. The author, David Hynes, has written about his motivation and approach to this collection for Centenary News.

How exactly are we supposed to commemorate the First World War?

Through silent contemplation? By bowing our heads as we hurry past the village memorial? By wearing a crumpled poppy at our breasts?

Well, it all really comes down to whether the First World War still means anything for us. If it’s simply too distant a thing for people to care about any commemoration can only ever be perfunctory in nature.

And this is the great fear about the Great War. Lest We Forget may be emblazoned in our minds as a promise we are meant to keep to those who lost their lives, yet we know too that all things come to pass. All causes begin to fade.

So the question I asked myself as I approached the Great War’s Centenary was; what can it mean to me? Not should, but could. What personal relevance might I find in it all?

Well, quite a lot, as it transpired.

In fact, as I researched more I discovered the centenary represents both a great disconnect and a great continuity in British society and British people.

One the one hand the Great War feels like a millennia ago to people like me. My own conscription has been to go to university and then get a job. Hardly going over the top, is it?

I, like you, may have been living in a recession for the last seven years, but a recession is not a trench, and a frustrating internet connection has nothing on an enemy tank. Not really.

On the other hand, ordinary people, just like you and me, were asked to do an extraordinary thing,-to go to war, en masse-just one hundred years ago. Some didn’t want to go at all, some went with enthusiasm and many went simply because that they had been told to go. I can relate to this-just about. Why? Because it speaks of personal reactions, it speaks of people being caught up in something they don’t fully understand. It speaks of spontaneity. This is a universal theme.

Sometimes we think of the past in too grandiose terms. We think that what we sculpt marble for, what we wear poppies for, is untouchably exalted. It belongs to the exotic and distant past.

This is not the case.

If you’re interested in how your own society may be viewed in a hundred years’ time, perhaps you should examine how you view one a hundred years ago. If you think the world’s problems appear to us with clarity today, you’re plain wrong. The future is waiting to give its verdict.

This, then, is why we should commemorate the Great War; because we are interested in people.

And if you don’t take an interest on its anniversary-on its great, big, fat 100th birthday- will you ever? The next big thing in the Great War’s diary, let’s face it, is the two hundred years mark and, cynical as I am, I don’t hold out too much hope our offspring will be digging ditches in their backyard on August 4th 2114 to investigate the vicariousness of trench-life.

We are the last rememberers. This was the motivation to begin my anthology.

And so, I began to compose some poems. Just a few to start with- quirky, off-kilter poems focusing on what the war might mean to us today. In Daddy, I have a young child asking her father what he is planning to do to commemorate the Great War. In The Didsbury War Memorial I compare the memorial’s incongruous place between the supermarkets and shops of an affluent suburb in Manchester. in Hear It, I imagine the Armistice Bells heard along Oxford Street, London. In The Ditch, I imagine a man digging a trench in his own back yard in testimony to the fallen.

Many of the poems are deliberately removed from the conventional, sombre and maudlin ones we’ve inherited from Owen and Sassoon et al. This is not to denigrate the legacy of the Great War’s poetry, but to recognized people need to be shown why the war is still relevant to them, one hundred years on.

-David Hynes

For more information about This Thing of Memory, click here