As commemorations begin for the centenary of the Third Battle of Ypres-Passchendaele, ex BBC correspondent and author Tim Luard recalls the harrowing experiences of his great aunt, Kate Luard, as a senior nurse just behind the front line in Flanders.

In the summer of 1917, Kate Luard held one of the most responsible, and dangerous, nursing positions of the Great War.

She was Head Sister of No 32 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS 32) – an experimental specialist unit dealing with abdominal and chest wounds — when in July 1917 it was moved up to Brandhoek to serve the push that was to become the Battle of Passchendaele.

Since their camp was only just behind the front line and also near a munitions dump and a strategic railhead, she and her staff of 40 nurses and nearly 100 orderlies soon found shells and bombs flying over their heads in both directions – and often landing in the compound itself.

In the early morning of July 31, as the British attack began, Kate wrote excitedly in her diary of the “glare before daylight of the searchlights, starshells and gun flashes, and the cracking and splitting and thundering of guns of all calibres.”

It was “brighter than any lightning, dazzling and beautiful – more wonderful and stupendous than horrible.”

But her front-row view of the battle soon proved too close for comfort as pieces of shrapnel burst through the canvas huts in the nurses’ quarters.

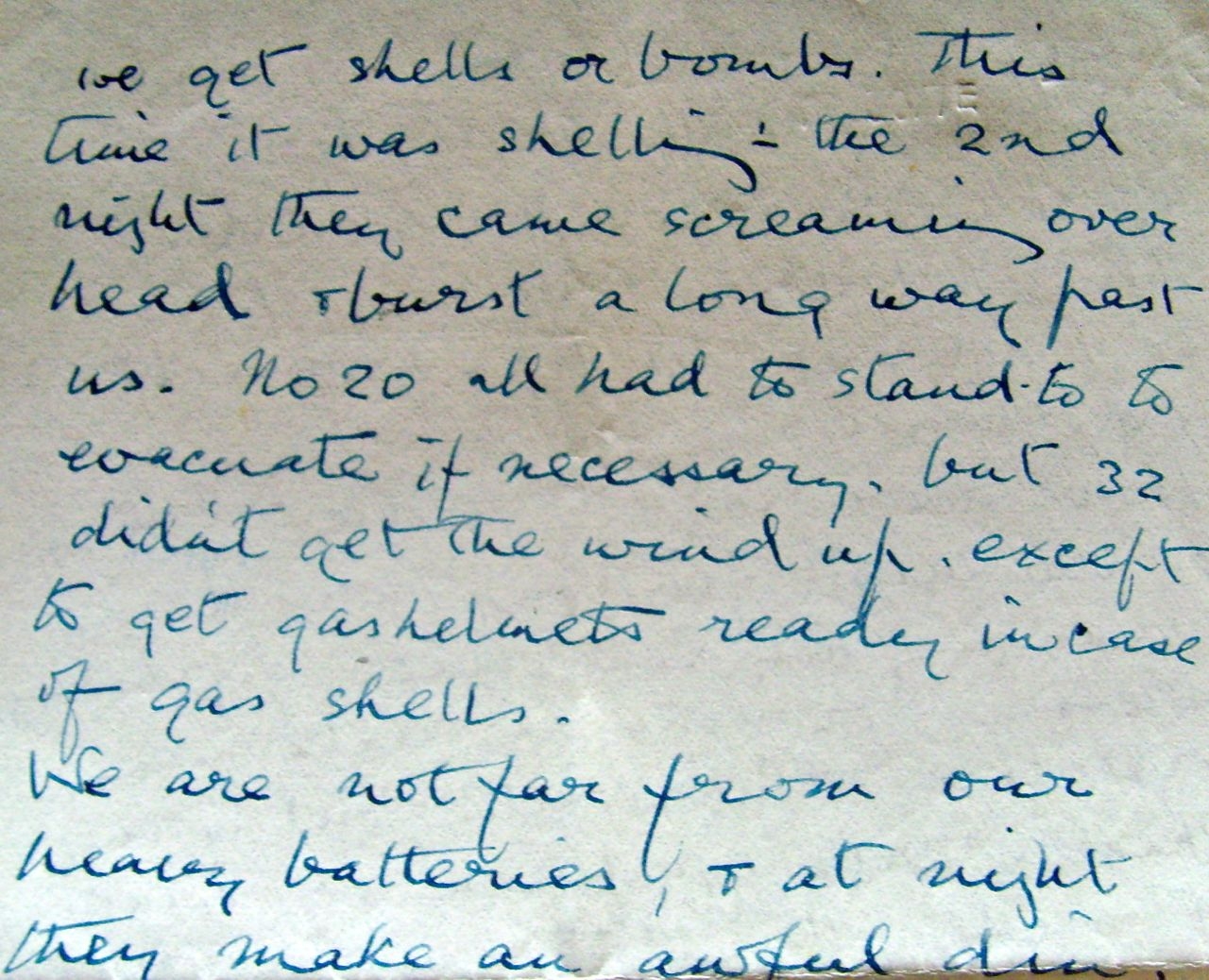

One of Kate’s letters, describing the shelling of CCS 32 in the summer of 1917 (Image: Luard /Essex Record Office)

“Shells and bombs shave us on all four sides,” said Kate in one of hundreds of letters she sent home to her father, brothers and sisters at Birch Rectory, the family home near Colchester in Essex. “We have been working in the roar of battle every minute … and it has been rather too exciting.”

“Bursting shells are an ugly sight,”she went on — “black or yellow smoke and streams of jagged steel flying violently in all directions.”

Gas

Many of the shells carried the Germans’ new, blinding weapon known as mustard oil gas. “It burns your eyes,” she reported. “Sounds jolly, doesn’t it?”

The nurses put on tin hats and gas helmets and carried on, overwhelmed as they were with patients in the first days of the fighting.

They were violently jogged every few seconds by the concussion of the almost constant bombardment, making surgical operations with the rudimentary equipment of the time more hazardous than ever.

But the closeness of the new unit to the front line meant that men who would have died of their wounds on a longer journey could be saved by operations performed within an hour or two of getting hit, instead of the three days that had sometimes been the case in the past.

Experienced

Born in 1872, the tenth of 13 children of a country vicar, Katherine Evelyn Luard (known as Evie to her family) had served as a military nurse in the Boer War and had gone on to use her experience in most key battle areas in World War One, working on ambulance trains, field ambulances, casualty clearing stations and base hospitals in France and Belgium.

The 30 medical officers in her latest unit in Flanders included 12 operating surgeons, with theatre teams working on eight tables continuously for 24 hours. The staff worked 16 hours on and eight off, though frequently they just carried on till they dropped. “They have sent some very good Sisters up – all as keen as ninepence”, Kate noted approvingly.”They never let one down.”

There were huge marquees for wards and mess tents, while the operating theatre was in a wooden hut. Nurses’ quarters consisted of bell-tents.

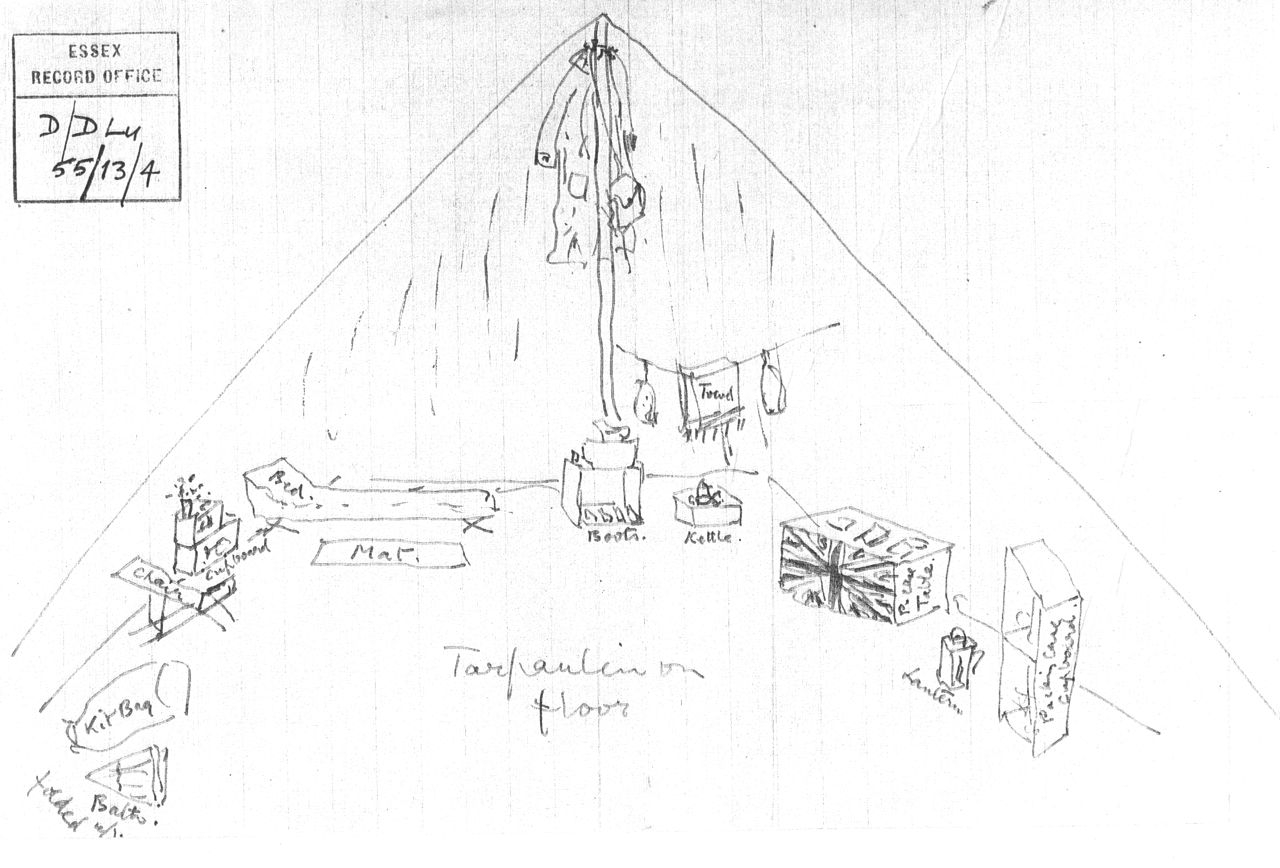

A sketch Kate made of her own tent shows a camp bed, folding bath, kettle and lantern, with packing cases serving as cupboards and tables. Her letter box was the brass case of a 4.5 howitzer shell (Image: Luard /Essex Record Office)

A sketch Kate made of her own tent shows a camp bed, folding bath, kettle and lantern, with packing cases serving as cupboards and tables. Her letter box was the brass case of a 4.5 howitzer shell (Image: Luard /Essex Record Office)

“There is a fine broad duck-walk all down the middle of the Hospital”, she wrote, “with the Wards on each side, which in the evenings is a sort of Rotten Row for Surgeons and Sisters on their late round, where you compare notes and watch the barrage. The topics are exclusively abdomens, guns, Huns, shells and bombs!”

She describes the wards as being “like battlefields, with battered wrecks in every bed and on stretchers between the beds and down the middles. The Padre is wonderful: he fills hot bottles with his one arm and gives drinks and holds basins for them to be sick, and especially looks after those poor ghastly moribunds.”

These ‘battlefields’, she says, “bring out the best in everyone….’We have huge jokes in the middle of it all… The patients themselves, as always, establish their own intimate personal relation at once with us all—Sisters, Orderlies and Medical Officers—as soon as they are out of the anæsthetic. Nothing is spared to pull them through; eggs at any price, unlimited champagne, port, stout, fresh milk, chicken, porridge and everything you can’t get at the Base. The Quartermaster scours the towns every day in a lorry.”

Noel Chavasse VC

It was here at Brandhoek, on August 2, 1917, that Captain Noel Chavasse — the only man to receive a Victoria Cross twice for actions in the First World War — had his multiple wounds treated by Kate and her colleagues. “He is loved by everybody”, she wrote.”He tries hard to live — he was going to be married.” But he died two days later.

Kate went to his funeral, where “his horse was led in front and then the pipers and masses of kilted officers followed. Our Padre with his one arm looked like a Prophet towering over everybody and saying it all without book. After the blessing one Piper came to the graveside (a large pit full of dead soldiers sewn up in canvas) and played a lament. Then his Colonel, who particularly loved him, stood and saluted him in his grave. It was fine, but horribly choky.”

In the early days of August the area was saturated with its heaviest rainfall for years, holding up the British advance. The wounded were brought in sopping wet, their eyes and mouths covered in mud. Tents leaked or even collapsed, and the water in some wards came halfway up the legs of the beds.

“The rain continues, all night and all day,” wrote Kate.”Can God be on our side, everyone is asking, when his (alleged!) Department always intervenes in favour of the enemy at all our best moments?”

Tyne Cot, the largest Commonweath cemetery in the world, where almost 12,000 soldiers who fell on the battlefields of Passchendaele and Langemarck are buried(Photo: Centenary News)

Tyne Cot, the largest Commonweath cemetery in the world, where almost 12,000 soldiers who fell on the battlefields of Passchendaele and Langemarck are buried(Photo: Centenary News)

On the night of August 22 a shell that burst between the wards killed a night sister and knocked out three others. In letter to her closest sister, Georgina, the normally indomitable Kate admitted that sometimes it all became too much for her.

“I think I am getting rather tired and have got to the stage of not knowing when to stop. When I do I immediately begin to cry of all the tomfool things to do! It is the dirtiness and wasted effort of War that clouds one’s vision … but we had 56 funerals today so can you wonder?”

As well as all her other duties, Kate had to write what she called ‘break-the-news’ letters to the families of those who died. In one week alone she built up a backlog of 209 of these. In a sign that she sometimes may have struggled to keep up, one mother wrote thanking her for telling her about her son but adding that “it would relieve the news somewhat if she knew which son it was, as she had three sons in France.”

‘Tubby’ Clayton

Kate Luard was the only woman to go ‘down the line’ to Talbot House, or Toc H, the famous rest home for soldiers in Poperinge, where she climbed the steep stairs to the tiny chapel built into the roof to receive communion from its founder, the Reverend ‘Tubby’ Clayton.

He later wrote that very few surviving men had served in more constant danger than she had. Of her writings about the war, he said “each page is vibrant with two great themes – the awful waste of men, and the shy splendour that was in them. Here is an eye and pen at work upon the spot. Here is the evidence of a noble and acute mind, put down without rose spectacles. No one can read it without hating war; no one can read it without a deepened reverence for ordinary men.”

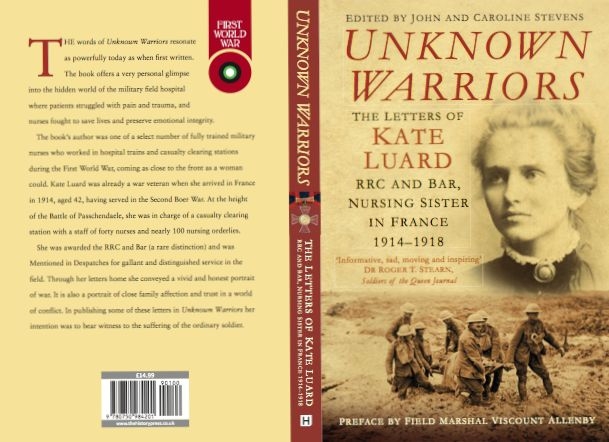

A new edition of ‘Unknown Warriors, the letters of Kate Luard, RRC and Bar’, was published by the History Press in 2014 A paperback edition was released in May 2017.

Discover more about Kate Luard’s nursing and writing here. An appreciation of her life and work can also be found in another article by Tim Luard for Centenary News.

Discover more about Kate Luard’s nursing and writing here. An appreciation of her life and work can also be found in another article by Tim Luard for Centenary News.

© Centenary News & Tim Luard

Images courtesy of Essex Record Office/Luard Family Collection; Centenary News (Tyne Cot)