Dr. Jillian Davidson writes for Centenary News about three London museums which are holding exhibitions related to the First World War.

Three very different London museums have, this summer, featured important exhibitions about World War One.

The first of these museums is the Dulwich Picture Gallery, which is the oldest public art gallery in England, having opened in 1817.

The second is the Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood, which was originally founded in 1872 as the Bethnal Green Museum. After the museum was closed during the First World War for safer storage of its objects, it gradually became transformed into the Museum of Childhood in 1974.

The youngest and smallest of the three, the Hackney Museum, was established in 1986 to celebrate the diverse, immigrant communities of Hackney’s neighbourhood.

On display at Dulwich until September 22, 2013 are the works of six artists — Paul Nash (1889-1946), C.R.W. Nevinson (also 1889-1946), Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), Mark Gertler (1891-1939), Dora Carrington (1893-1932), and David Bomberg (1890-1957).

“A Crisis of Brilliance”

All six were pupils at the Slade School of Art, all came under the tutelage of the notoriously demanding Slade School teacher, the surgeon and artist, Henry Tonks. The exhibition’s title, “A Crisis of Brilliance” in fact refers to Tonks’ verdict concerning this second generation of Slade art students.

They, and their peers, who included the poet Isaac Rosenberg, were photographed while on a school picnic c. 1912. They were a class of students trying out various techniques, responding to different influences, honing their skills and forging their personal styles when World War One broke out and impacted on the course of their artistic education.

Slade School of Art picnic, c. 1912

The Dulwich exhibition is the natural offshoot of David Boyd Haycock’s group biography “A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young Artists and the Great War” (2010). To the original quintet, David Bomberg was only later added.

Yet, it is Bomberg’s tremendous oil on canvas of 1913-14, “In the Hold,” which stands on display, significantly, at the threshold of the exhibition.

At first sight, the painting, divided into sixty-four squares, resembles more of an abstract, geometric pattern than any real, human narrative, but as Bomberg himself insisted, it portrayed “men emerging from one trap door and entering another in the hold of a ship,” an experience familiar to the son of Polish Jewish refugees, but also one which best captures the liminal condition of this group of artists emerging from the Slade School and entering a world engulfed by war.

The exhibition graphically relates the war paths of these artists: the four who enlisted, although without enthusiasm — Nash, Nevinson, Spencer and Bomberg, though he was at first rejected on account of his accent and scruffy appearance; Carrington, who did her best to ignore the war and devote herself to Lytton Strachey; Gertler who hated the war and was considered a pacifist.

War artists

In 1916, the British government introduced not only conscription but also a commission of artists to record the War.

Nash, who joined the commission following the advice of Nevinson, lamented to his wife from the Western Front: “I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from men fighting to those who want the war to last forever.

Feeble, inarticulate will be my message but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls.” Bomberg became an official artist for the Canadian government commission. The British government invited Gertler to join as an artist of the homeland, but he declined the offer.

‘Merry-Go-Round’

Reviews of “A crisis of brilliance” have tended to focus on the absence of Gertler’s greatest achievement, his so-called “anti-war” painting, ‘Merry-Go-Round.’

Writing for The Spectator, Andrew Lambirth felt that Carrington’s portrait of Lytton Strachey, quoted in the exhibit’s catalogue as “a work of defiance and of pacifism comparable to ‘Merry-go-Round’”, cannot compensate for the lack of Gertler’s masterpiece. “Where is the ‘Merry-go-Round’ — wouldn’t the Tate lend it? Obviously an exhibition space the size of Dulwich’s can only accommodate a certain number of large paintings, but surely any exhibition dealing with Gertler and the first world war cannot do without his most succinct and forceful anti-war statement?” (20 July 2013) Similarly, The Economist reported that, “It is a shame that Gertler’s wartime masterpiece, ‘Merry-Go-Round’ (1916), hanging in Tate Britain, is missing from this show, as is Nash’s important 1919 work ‘The Menin Road.’” (22 June 2013)

To leave Dulwich disappointed is, however, to miss the point. True, Gertler’s ‘Merry-Go-Round’ cannot be seen, but his Study of Heads for ‘Merry-Go-Round’ (1915) can, as can Spencer’s Study for ‘John Donne Arriving in Heaven’ (1911), Spencer’s Study for ‘The Visitation’ (c. 1912), Bomberg’s Study for ‘In the Hold’ (1913-14), Nevinson’s Study for ‘Column on the March’ (c. 1914), and Bomberg’s Study for ‘Sappers at work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St. Eloi’ (1918-19). Gertler’s Study of Heads for ‘Merry-Go-Round’ actually shows the great influence of his teacher, Tonks, whose Half-length Study of a Seated Girl is also present.

The juxtaposition of Tonks’ Annotated demonstration: Drawings and a Study of a Girl’s Head (1908) and Gertler’s Study of Heads for ‘Merry-Go-Round’ offers an almost uncanny comparison. Furthermore, accompanying each piece of art is the information of its year of creation, plus the age of the artist at that time.

On initial viewing, this constant repetition of the artist’s age seems rather superfluous, but, upon reflection, this aids to emphasize the main thrust of the exhibit: to trace the artistic development and journey of six young students, emerging from the Slade School of Art into the First World War.

War toys

The second exhibit, which is at the V&A Museum of Childhood until 9 March 2014, is “War Games.” This panorama of military toys invites visitors to explore an entirely different facet of schooling: the “secret, shocking and surprising ways” in which imaginary war games have trained, influenced, comforted, healed and even aided escape.

This exhibit, far from setting out with a one-sided, pre-conceived agenda to condemn recreation with toy weapons, is open-minded to the possible positive benefits of imaginative play: “they can teleport, transform and make people better.”

Spanning a period from 1800 to the present, from the eve of the industrial revolution to the era post computer revolution, the First World War looms large.

Toys helped in training and recruitment, in propaganda, in patriotism, in messages of heroism, in circulating information, as a source of humour and as an avenue of charity and rehabilitation. Sample exhibits of these included a “Get Rid of Huns” board game, given to a 10 year-old boy, Jack Cripps in 1916.

As a way of projecting the German Huns as barbarians, the Huns were represented by four different coloured devils. There was a Lord Kitchener doll of 1915. There were books that explained the first use of poisonous gas in the War. There were aviation board games to match the technological innovations in war. A new range of miniature cardboard trenches, with toy barbed wire and machine gun crews was one result of trench warfare. There was the British Tommy Doll, Ole Bill, modelled after the cartoon character. There were even toy injured soldiers, dressed in “hospital” or “Convalescent Blues,” made by Boots the Chemist and sold to raise money for charity. Toy making had long been part of the rehabilitation of injured servicemen. A painting by John Hodgson Lobley, another official war artist for the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War One, shows soldiers at work in the toy-makers’ shop at Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries.

The Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries, Frognal, Sidcup: The toy-makers’ shop, 1918, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, ART 3756

Equally edifying is the exhibit’s companion War Games Perspectives Web pages, which offer different perspectives on the exhibition, including an essay on “Toy Soldiers and the First World War” by Professor Kenneth Brown.

Hackney Remembers

The third exhibit, “Hackney remembers”, which explores the story of how the First World War changed the lives of local people nearly 100 years ago, is at the Hackney Museum until September 30th. It then transfers to the Jewish Military Museum, London until the New Year, when it will travel to local schools in Hackney throughout 2014.

An online resource pack will soon be readily available for teachers to help them plan their school projects in time for the centenary.

Even more pronounced in this exhibition is, therefore, the role and theme of education. The culmination of a local heritage project, Fifth Word Theatre in partnership with Hackney Museum, the Jewish Military Museum, Hackney Archives and community volunteers trained Year 6 pupils from St John and St James Primary School and Springfield Primary School to select from 69 archival items the themes and stories which they found most interesting.

They then created mock exhibition panels, which were turned into professional printed materials. Yes, incredible as it may seem, this exhibition was curated by eleven-year-old schoolchildren!

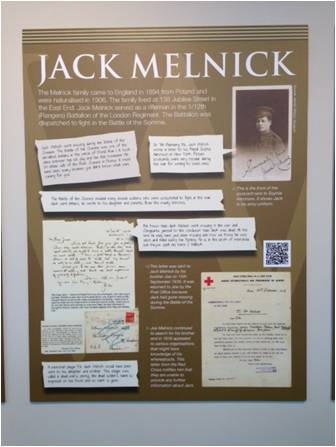

Take, for example, the war story of Jack Melnick as prepared first in the hands of the schoolchildren and then as mounted on the museum wall. The story, which they uncovered and presented, told of a family which came to England from Poland in 1894 and lived at 138 Jubilee Street in the East End.

Jack Melnick served as a rifleman in the 1/12th Battalion of the London Regiment. He went missing during the Battle of the Somme.

His brother, Joe, appealed to organizations for knowledge of his whereabouts. The students chose to include on their panel a letter from the Red Cross, which said that they were unable to provide any information about Jack. The students superimposed their own commentary: “now we know that he was shot and killed during the fighting.”

Springfield Primary School students present their exhibition panel mock up design for Jack Melnick, 2013

Springfield Primary School students present their exhibition panel mock up design for Jack Melnick, 2013

If this is the kind of brilliance, exhibited in the summer of 2013, there is surely much to look forward to when the centenary actually arrives.

The Jack Melnick exhibition panel, 2013

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author