The Canadian War Museum’s latest Centenary exhibition, running until April 26th 2015, is dedicated to the experience of Canada on the Western Front during the First World War. Centenary News writer, Christopher Harvie, reports.

‘Fighting in Flanders – Gas. Mud. Memory’ examines the challenges Canadian soldiers encountered while serving in the last region of Belgium still in Allied hands. It also highlights the iconic poem In Flanders Fields and “explores how the collective memories of the First World War have evolved among both Canadians and Belgians over the past 100 years.”

Their experiences are shared through works of art, personal stories, photographs, archival materials, audiovisual presentations and more. The content is drawn from the Canadian War Museum’s own collections, as well as from other institutions in Canada and Europe.

“Gas. Mud. Memory.” relates to the themes and events examined by the exhibition.

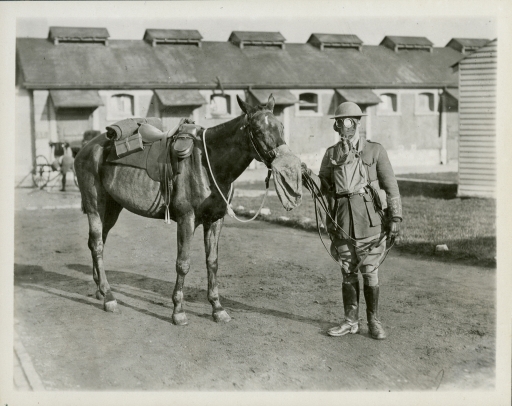

Gas

Fighting in Flanders begins by establishing the context for Canada’s entry into the First World War. In 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Canadian forces endured clouds of chlorine gas to hold the Allied line.

Throughout April 23rd, Canadian lines were continually shelled while the Germans prepared to renew their attack. Again gas would be used as a preliminary to infantry assault, and it would fall upon the centre of the Canadian line, at the boundary between 2 and 3 Brigade. Shelling had intensified and just before first light a cloud of chlorine was released. The 8th and 15th Battalions took the brunt of this. Despite heavy losses, confusion and malfunctioning weapons, these untested troops managed to hold out against difficult odds.

By the time the Division was withdrawn, it had taken 5,400 casualties, 1,737 of which were fatal, or about a quarter of its strength. Praise for the 1st Canadian Division came from the highest levels.

Field Marshal Sir John French, British Commander-in-Chief, said: “In spite of the danger to which they were exposed, the Canadians held their ground with a magnificent display of tenacity and courage, and it is not too much to say that the bearing and conduct of these splendid troops averted a disaster”

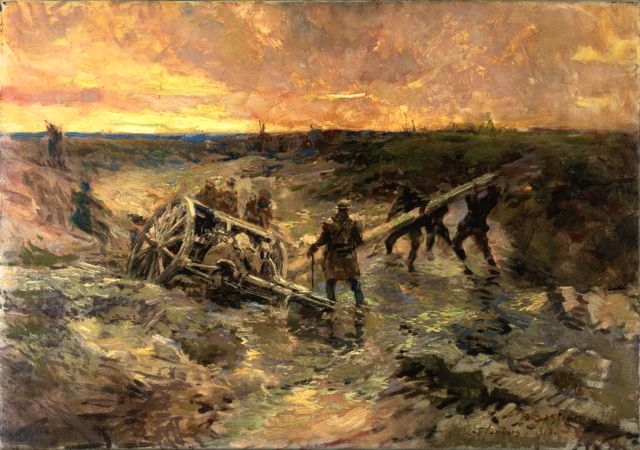

Mud

In 1917, the Canadians fought for weeks through mud, heavy artillery and machine gun fire to prevail in the Battle of Passchendaele, Over sixteen days, in one of the most miserably rainy autumns on record, the Canadian Corps struggled forward through diabolical mud.

Canadian Gunners in the Mud, Passchendaele, painted by the Belgian artist, Alfred Bastien, in 1917 (Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum 19710261-0093)

Years of continuous shelling in an area with a low water table mixed with unseasonably heavy rain had turned the Ypres area into a horrific mess: “Of all the battlefields in which Canadians fought during this war, Passchendaele was by far the worst,” writes John Marteinson in his illustrated history of the Canadian Army, We Stand on Guard.

The attack would have to be made across hundreds of yards of glutinous mud, defended by the interlocking fire from concrete pillboxes and dense barbed-wire entanglements of the carefully engineered German defences.

Momentum was staggeringly slow, the terrain deep in muck and littered with waterlogged shell holes that were death traps for the wounded. As the Divisions advanced, unit cohesion devolved as elements worked around the wire obstacles and thick-walled bunkers. Often the battle was reduced to skirmishes of platoon and section strength rather than massed assault. By November 10th 1917, the Canadians held Passchendaele Ridge, at a cost of 15,654 casualties.

Memory

The final section of the exhibition focuses on how the First World War continues to be commemorated. These memories are brought into sharp focus with Canadian John McCrae’s well-known poem In Flanders Fields, which led to the adoption of the poppy as a symbol of Remembrance Day and continues to inspire reflection on war and sacrifice.

Lieutenant Colonel McCrae’s lines have become a touchstone for remembering those that fell in the Great War, and is well known worldwide. His experience and inspiration for the poem may not be as well known outside Canada.

As a surgeon, McCrae would have been familiar with disease, suffering and death that even in civilian practice would have been beyond our understanding in this advanced age. But not even a doctor of his experience could have been prepared for the volume and type of wounds he was to encounter at his aid post during the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915.

The nature of his work would place him well behind the firing line, the place known as the “forward edge of battle”, but his post would have been close enough to the artillery to see the flash, hear and feel the blast of outgoing shells, and to smell the heavy and sweetly metallic scent of carbon and burnt cordite from the big guns. This smell would have mixed with that of his patients’ wounds, the rusty whiff of blood and perhaps a faint chemical tingle of chlorine gas that was dissipating through a strong westerly breeze.

John McCrae worked solidly as men were brought to his care, more perhaps than he was prepared for at any one time. He took a short break only when word was passed to him that a friend had been killed in the fighting.

It was during this moment to himself that he composed In Flanders Fields, expressing the personal grief that was to become a fitting memorial to all who died in the war.

The closing date of the exhibition, April 26th 2015, coincides with the 100th anniversary of McCrae’s writing of “In Flanders Fields.”

‘Fighting in Flanders – Gas. Mud. Memory’ is supported by VisitFlanders and is part of a series of projects commemorating the Centenary of the First World War at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. “As National Presenting Sponsor of this exhibition, we would like to honor Canada’s incredible support of our region and all the brave women and men who served in Flanders Fields,” says Peter De Wilde, CEO of VisitFlanders.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author

Images courtesy of the Canadian War Museum ref: 19930003-453 (soldier & horse in gas masks) and Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum ref: 19710261-0093 (Canadian Gunners in the Mud, Alfred Bastien, 1917)