A unique digital project is telling the story of the First World War through the private letters of nine different men from several countries who died in the fighting.

The War Letters 1914-1918 website and series of e-books reveal an intimate and moving insight into life at the front using the men’s own words.

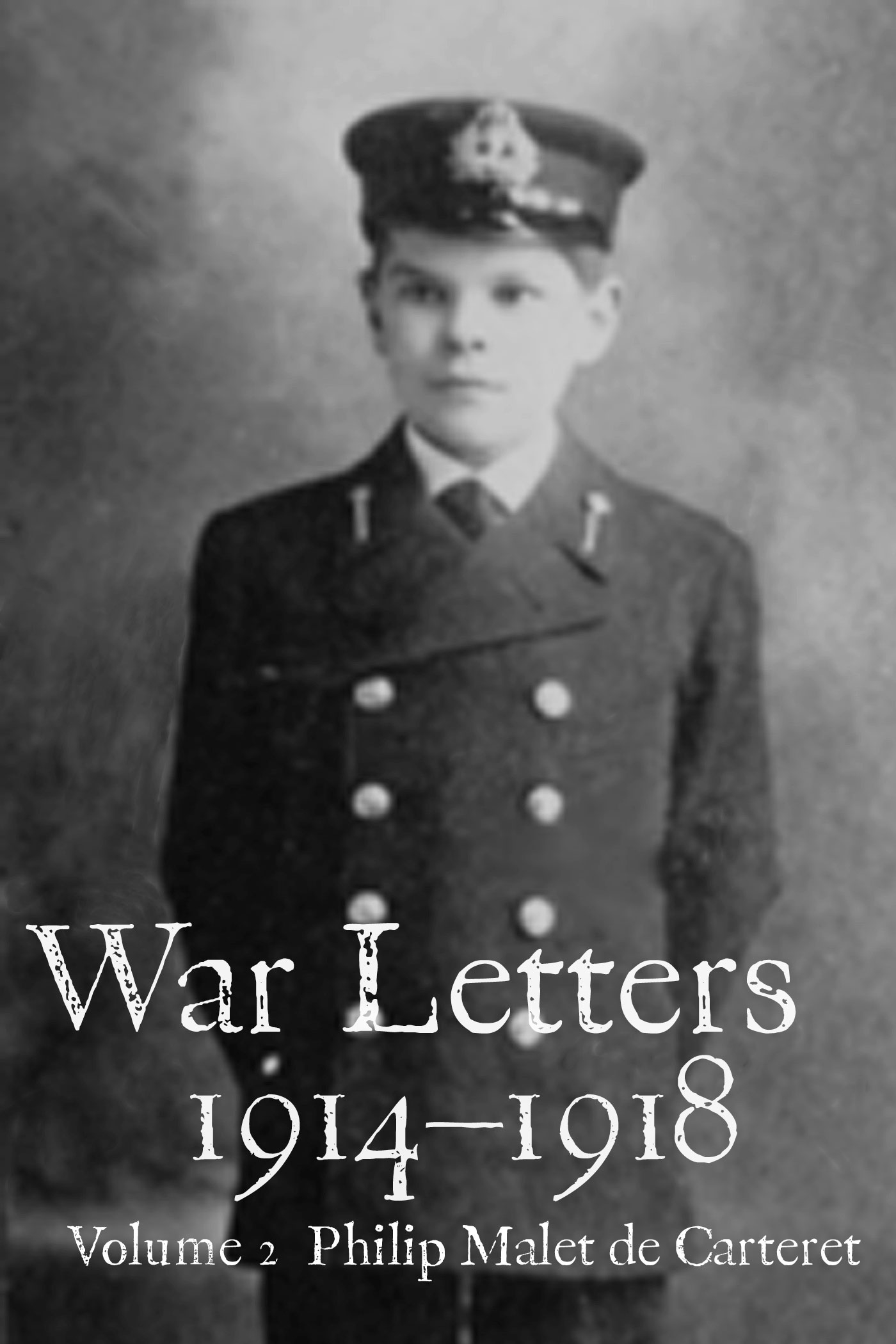

The first e-book is based on the letters of seventeen year old Wilbert Spencer, a pupil at Dulwich College, private school in South London, who joined up to be a British officer in August 1914 only to die eight months later. Two other e-books will also be published in June 2014 and the others over the next four years to tell a consecutive story of the war.

Compiled over ten years of painstaking research, they record the experiences of four British servicemen, including the last a pilot shot down over Germany in November 1918. The remaining stories come from two Australians, one New Zealander, a Canadian and an American.

They cover the evolution of the war on the Western Front, the fighting at Gallipoli and Mesopotamia and the war at sea and in the air.

Here editor Mark Tanner, in a special report for Centenary News, tells of the emotional effect the private letters had on him and how digital records and e-book publishing gave him the opportunity to tell the stories of the men in a new way to a modern internet audience.

Ten years ago I was researching material for a number of short films about the last letters soldiers had written before they died on the battlefield. As I sat in the old circular reading room of the Imperial War Museum in London ordering collection after collection of soldiers’ letters, I came upon those of Wilbert Spencer that now feature in the first book of the series.

As I read them, his young, exuberant, gentle character formed a hugely powerful image in my mind. It was as if time had dissolved and I could almost see and hear him speak.

His death when it came, so abruptly and at such a young age, felt as if someone I knew had died. Even now, over ten years later, having read and re-read his letters countless times, they still have the same emotional effect on me.

This is the most awful part of the war

It was the power of these letters that gave me the initial idea of compiling a book that would tell a history of the First World War using the words of men, like Wilbert, who had died in the conflict.

In January 1915, he wrote: “On New Year’s Day we had our first dose of shrapnel and shell. One shot burst right in our trench, killed one poor fellow and wounded four. This is the most awful part of the war. The fellow who was killed lived his last few minutes with his head on my knee. Thank God they are usually unconscious and can suffer little pain. Luckily the Germans didn’t get the rest of their shots in.”

Any spare moment I had was spent scouring different archives and collections, reading hundreds and hundreds of letters and laboriously transcribing faded, sometimes hardly legible handwriting. Eventually the letters that make up the War Letters 1914–1918 series began to emerge and take shape.

Copyright Mark Tanner

Copyright Mark Tanner

The letters are drawn from archives and personal collections all over the world.

Read consecutively, they tell a story of the war from 4 August 1914, when the seventeen-year-old Wilbert Spencer decided he wanted to become an officer, until 10 November 1918 when a young British pilot dies as his plane is shot down over Germany.

Regrettably, they do not contain the experiences of soldiers from India nor the West Indies. Such letters that would have fitted in the format of this series are simply impossible to find.

Letters written by Indian soldiers, have as David Omissi, author of Indian Voices of the Great War, says ‘been lost long ago in Punjabi or Nepalese villages.’ A similar fate has been suffered by those letters sent back to the West Indies.

The men selected, however, do have an important story to tell. Contrary to the perception of a generation unable to express their emotions, the letters reveal the deeply moving life of ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances. Their complex, sometimes contradictory responses at times reinforcing and at other times directly challenging modern views of the First World War.

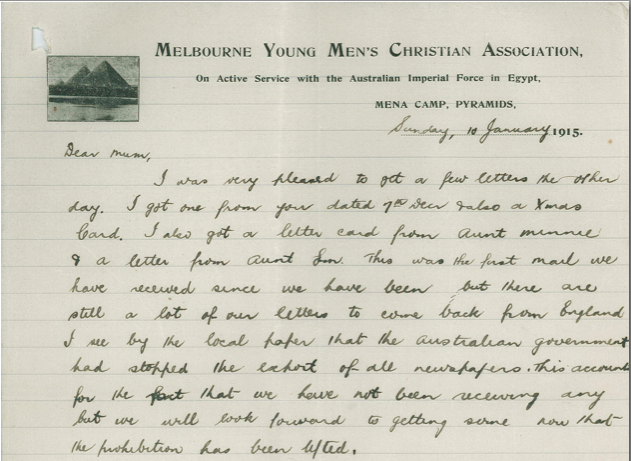

Extract from letter written by Frederick Muir from Egypt

Extract from letter written by Frederick Muir from Egypt

As I began to edit the letters, one principle became crystal clear. I didn’t want to interrupt the men’s voices with explanations from me, clarifying and explaining what they had and hadn’t said. The powerful experience of reading Wilbert’s letters as they were written made me to want to avoid this.

In their own words

That is why, in the books, the letters are presented as they are, with all their gaps, silences, ambiguities and contradictions. When read in this way, I think you can truly begin to immerse yourself in the men’s words and world and get a really strong sense of each individual.

The obvious difficulty with such an approach is how to effectively provide the bigger picture and fill in some of the gaps and details that are left unsaid.

Fortunately two connected developments provided an answer. The first was the almost exponential growth of online resources about the First World War: fascinating, important documents and material available to anyone in the world able to access the internet. The second was the emergence and rapid growth in popularity of the e-book, particularly the short e-book.

Online treasures

It was the desire to incorporate and share this constantly emerging treasure of resources scattered throughout the web, while still presenting the men’s own words as they were written, that made me realise that the e-book was the perfect vehicle to do this. It enables the letters to be read as they were written, but now comprehensive notes are just a click away.

Wherever possible those notes provide direct links to resources that are available online. Almost all those resources are also available through the War Letters 1914–1918 website.

I have focused on links which aren’t hidden behind paywalls, but which, in almost all cases, are open to access for all. The links don’t include Wikipedia but they do include official histories, battalion diaries, recordings of old songs, war memoirs, military training manuals, trench maps, documentary films, recruiting posters and much, much more.

Mesopotamia Campaign

My aim has been to provide a useful starting point for people wanting to discover more about the First World War. Most of this material was already there waiting to be found; some of it wasn’t. It took some persuasion, but eventually the Hathi Trust made the British official histories of the Mesopotamia campaign open access for all. Not able to find the Mesopotamia despatches anywhere in an accessible format I compiled them myself from the London Gazette and have put them online.

Now, with digitisation at the heart of the centenary activities of many archives and organisations we are going to see a vast amount of new resources come online. They permit anyone who wants to, to embark on their own journey of historical exploration and discovery by delving even more deeply into many more aspects of the war.

I intend to try and keep up with the best of the new material and hope that the War Letters 1914–1918 website itself will become a valuable resource and one to which people will want to return.

Mark has worked in television as a researcher and then producer making documentaries for the BBC and Channel 4. Films include “Dangerous Knowledge” and High Anxieties – the Mathematics of Chaos for BBC4

The first three books will be published exclusively by Amazon as Kindle books. Amazon has Kindle Apps available for every smartphone, tablet or computer.

To visit the War Letters 1914-1918 website, click here.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author