A British artist tells the story of her great uncle who fell on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in a new exhibition hosted by the UK National Archives in London.

Sarah Kogan has retraced the footsteps of Rifleman Barney Griew, inspired by the many letters, photographs and postcards that he sent home to his family from France in the first half of 1916 while serving as a map maker and scout.

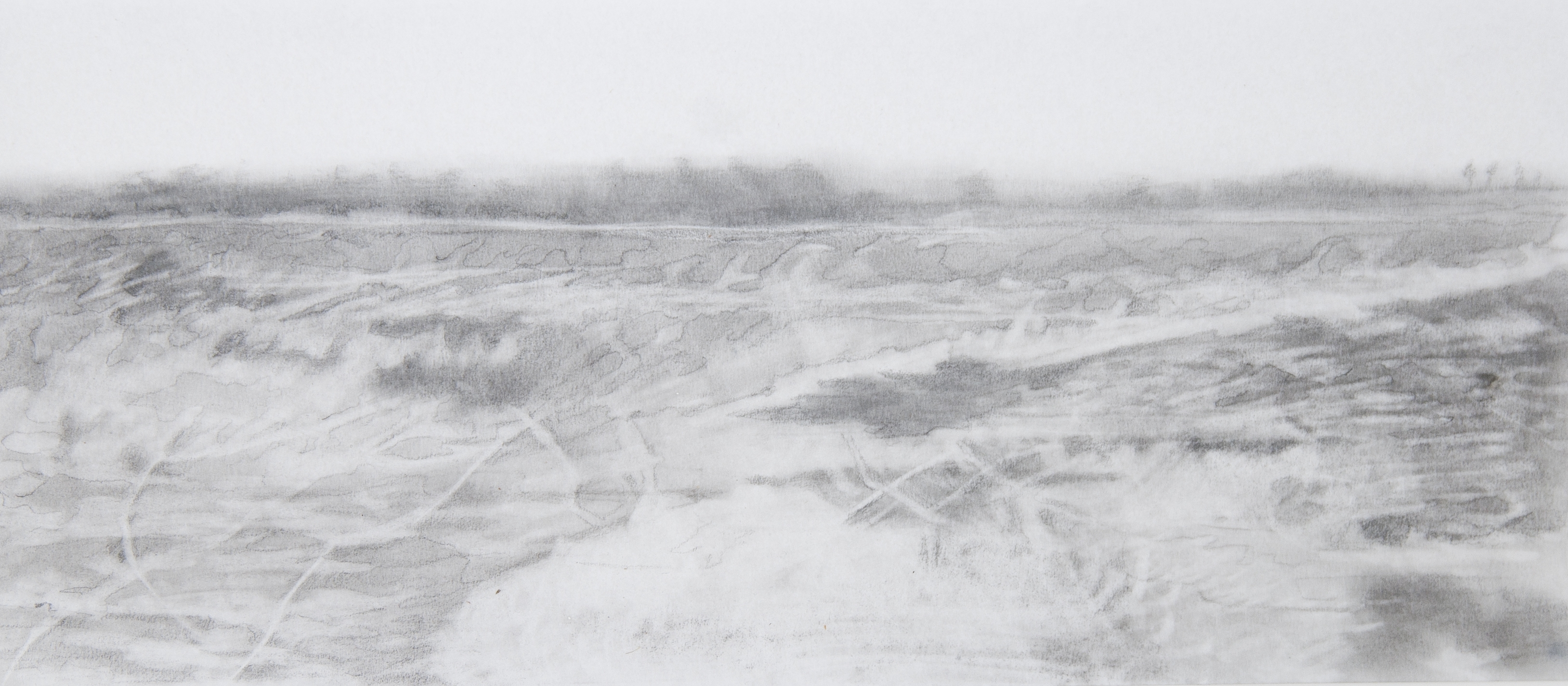

Using official military records she’s been able to identify the field where Barney’s remains still lie undiscovered after his death during a diversionary attack at Gommecourt on July 1st 1916.

“In the week leading up to the attack, Barney was being sent out every night to establish advance positions and to find out what was happening in the enemy trenches,” Sarah Kogan explains.

“From the official records, I knew that when Barney wrote home saying ‘eveything’s fine, I’ve just got back from a game of football,’ he had actually just got back from a sortie into no-man’s land.”

Sarah Kogan’s exhibition, entitled ‘Changing the Landscape’, also features her own artworks as a personal interpretation of her great uncle’s experiences in the First World War.

Gommecourt, Sarah Kogan 2013, caligraphy paper (Image © Sarah Kogan)

The exhibition is the culmination of five years of research, that started with piecing together Barney Griew’s prodigious archive of unpublished papers, a task captured in a video installation.

Griew, who came from a family of Jewish furniture makers in Hackney, east London, wrote home several times a day, providing revealing glimpses of a soldier’s life at the front in the build-up to the Battle of the Somme.

In May 1916, he noted: “I am quite happy with my scout job. To tell the truth I almost feel safer in front of than directly behind the trenches. I maintain that if a man gets hit it’s either his own fault or destiny”.

But as Sarah Kogan explains, her 20-year-old great uncle was an eloquent writer who expressed differing reflections in his letters to three members of the family.

“To my grandmother, he sent most of the photographs and the postcards. To his brother, Isaac, he confided in what was really happening. He always asks ‘how much shall I tell mother and father, shall I tell them I’m about to go into battle?’ Because of that he reveals everything that is going on,” Kogan told Centenary News.

“He has this very strong sense of legacy. He kept everything that he was given and sent it home.”

Glimpses of our (DG’s) sports day, by Barney Griew. The 20-year-old furniture maker was selected to be a map maker because of his drawing ability (Image © Gillian Kogan)

Poignantly Barney’s letters end on June 30th 1916, the eve of the Battle of the Somme.

“As usual doing nothing, he tells Isaac.

“We are moving about…I may not be able to write frequently in the near future. Will do my best though.”

Barney was among more than 19,000 British soldiers killed at the start of the Somme offensive on July 1st 1916, the bloodiest day in British military history.

The Griew family’s appeals for information about his fate are recorded in displays of press cuttings, together with a letter from the German authorities informing Solomon Griew that they weren’t holding his son.

Barney Griew is among the 72,000 names of the missing remembered on the Thiepval Memorial, the setting for this year’s UK/French commemorations on Juy 1st marking the centenary of the Battle of the Somme.

Sarah Kogan’s exhibition, presented as part of The National Archives First World War 100 programme, runs in the first floor reading rooms until September 17th 2016. More information about the project can be found on Changing the Landscape. It’s supported with UK National Lottery funding through Arts Council England.

Images courtesy of ©Sarah Kogan (Gommecourt 2013); ©Gillian Kogan (Sports Day 1916 – Barney Griew); Centenary News (Sarah Kogan at National Archives)

Posted by: Peter Alhadeff, Centenary News