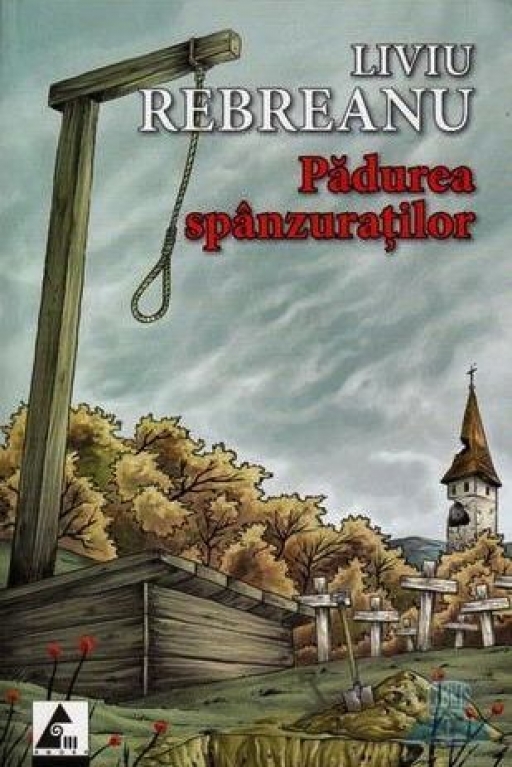

For the centenary of Romania’s entry into the Great War, CN contributor William Illsley reviews Liviu Rebreanu’s classic novel set during the Romanian campaign.

First published in 1922 in his native Romanian, Liviu Rebreanu’s Forest of the Hanged was originally translated by A.V. Wise and last published by Peter Owen, London in 1967. The author, Liviu Rebreanu worked as journalist during the war and regularly published short stories broaching the subject of public discontent and ill feeling, particularly in regards the Austro-Hungarian rule of Transylvania; he himself was extradited from Romania and imprisoned for illegally crossing the Transylvanian Alps to reside in Bucharest.

This resentment is deeply apparent within the Forest of the Hanged, though its narrative is inspired by something far more traumatic – the execution of his brother, Emil Rebreanu, for desertion in 1917. Indeed, the novel could be said to be a fictionalized account of his brother’s service; like the protagonist, Emil had been a decorated soldier lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian army, distinguishing himself in Galicia, Russia and on the Italian front. However, upon being called to the Romanian front in 1917, as an ethnic Romanian, Emil was forced to decide between his loyalty to the state he served and the nation he felt he belonged to.

Unlike many novels focusing on the graphic detail and trauma of the Western Front, Rebreanu takes a more philosophical approach questioning the very cause of what drives a man to fight and at what cost?

We follow Apostol Bologa, a young Romanian officer serving in the Austro-Hungarian army, opening with the execution of a Czech deserter in the eponymous forest. At this point, there is an evident sense of pride in duty, but in mirroring his brother’s experience, when called to fight on the Romanian front, Bologa is confronted by a growing crisis of conscience and the value of human life even when by law, the punishment was deemed just. This growing doubt is coerced by anarchist and pacifist elements as well as the discrimination against minority nationalities within the Austro-Hungarian ranks, reaching a climax when Bologa himself is faced with the question of whether to desert.

In some ways the novel can seem melodramatic; mutiny was of course seen in great numbers on all sides and the stark contrast between the main characters views at the start and his later actions could be considered wildly hypocritical, however no other book captures the internal wrangling of loyalty, treason and sense of belonging. So whilst the numerous nationalities fighting alongside allied regiments is well documented, in essence, it is an added narrative of victimization and nationalism rarely discussed and highlighted by this mournful and genuine exploration of the moral ambiguity of serving a country not of one’s own.

William Illsley read Forest of the Hanged in the 1967 English edition published by Peter Owen: London