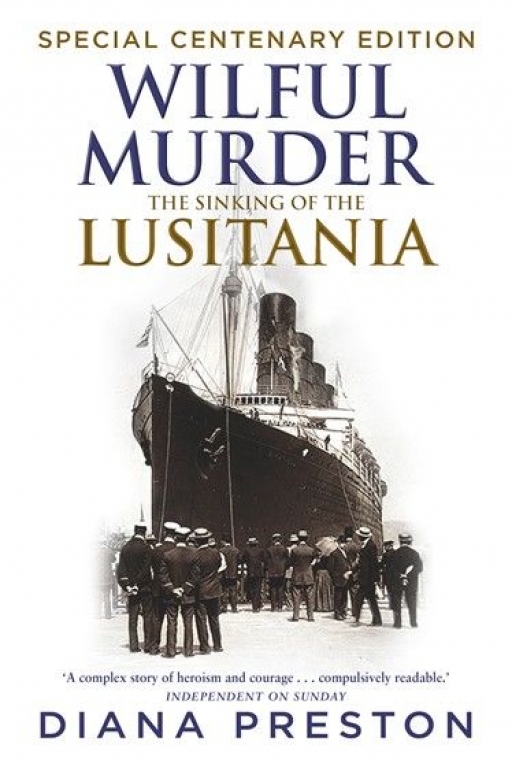

Publisher’s Description: ‘On May 7th, 1915 a passenger ship crossing the Atlantic sank with the loss of 1,200 lives. On board were some world-famous figures, including multimillionaire Alfred Vanderbilt. But this wasn’t the Titanic and there was no iceberg. The liner was the Lusitania and it was torpedoed by a German U-boat.

‘Wilful Murder is the hugely compelling story of the sinking of the Lusitania. The first book to look at the events in their full historical context, it is also the first to place the human dimension at its heart. Using first-hand accounts of the tragedy Diana Preston brings the characters to life, recreating the splendour of the liner as it set sail and the horror of its final moments. Using British, American and German research material she answers many of the unanswered and controversial questions surrounding the Lusitania: why didn’t Cunard listen to warnings that the ship would be a target of the Germans? Was the Lusitania sacrificed to bring the Americans into the War? What was really in the Lusitania’s hold? Was she armed? Had Cunard’s offices been infiltrated by German agents? And did the Kaiser’s decision to cease unrestricted U-boat warfare in response to international outrage expressed after the sinking effectively change the outcome of the First World War?’

Highly readable, meticulously researched, this special centenary edition casts dramatic new light on one of the world’s most famous maritime disasters.’

Centenary News Review:

Review by: Peter Alhadeff, Centenary News Deputy Editor

This is a lively and comprehensive account of the sinking of the Lusitania, its aftermath, and the controversies which still swirl around the disaster. Diana Preston weaves a narrative of intrigue and foreboding that describes how the pride of the Cunard fleet sailed into the sights of a German submarine off the Irish coast a century ago.

Preston’s book, first published in 2002, describes how anxiety hung over RMS Lusitania throughout her last voyage from New York to Liverpool. Yet we learn that the passengers could hardly believe their own eyes as they spotted the ‘fast-lengthening track’ of U-20’s newly-launched torpedo, even though in Preston’s words, they’d ‘all been thinking, dreaming, sleeping and eating submarines from the hour they left New York.’

Beneath the waves, a young conscript from Alsace on U-20 protested against attacking a ship carrying women and children. But Preston tells us that he was ignored by the submarine’s commanders, led by Captain Walter Schwieger.

The stories of the Lusitania’s passengers and crew who survived, and those who perished, are both inspiring and tragic. Lessons had been learned from the sinking of the Titanic only three years earlier. There were enough lifeboats. But the Lusitania listed so rapidly that it was difficult to launch them. Many experienced crewmen who could have helped were trapped below decks by the rapid failure of the liner’s power supply and the jamming of the lifts.

Large numbers of children were among the 1,198 people lost (1,201 including three anonymous stowaways) as the liner sank within 20 minutes of being torpedoed by U-20.

Diana Preston marshals an impressive amount of detail, without getting overly bogged down in the narrative. If at times she follows so many individual stories that it’s difficult to remember who’s who, you never lose sight of the overall drama and controversy. The actions of some of the Lusitania’s passengers and crew were truly heroic, those of others considerably less so.

Preston tests the multitude of conclusions, not to mention conspiracy theories (and sometimes the two are interchangeable), that have been attached to the why and wherefore of the disaster in the past 100 years.

The German accusation that the Lusitania was carrying ammunition and other ‘contraband’ was entirely correct, Diana Preston says. But it did not justify a ‘sink on sight’ policy. The evidence that the liner was unarmed is overwhelming, she argues. There were at least two explosions, the first caused by U-20’s torpedo shot. But the most likely cause of the second is put down to a catastrophic failure in the ship’s steamlines, carrying high-pressure superheated steam from the boilers to the turbines, rather another torpedo, or exploding munitions as the British and Americans privately feared.

As for the idea that Britain allowed the Lusitania to be attacked with the aim of bringing America into the war, it’s rejected. General warnings of U-boat activity were issued to commercial shipping, although the Admiralty didn’t institute special measures to protect the Lusitania, despite the Cunarder’s special significance.

Diana Preston points out that the British Government was preoccupied with the faltering campaign at Gallipoli, where the Allied landings had taken place less than two weeks previously. Reporting the centenary commemorations now, I’m reminded how close together these events were. In May 1915, Winston Churchill was at loggerheads with the professional head of the Royal Navy, Admiral Fisher. Both were out of their jobs by the end of the month.

With this in mind, Preston argues that the Lusitania in her last days and hours was the victim of British complacency and neglect: “While neither a verdict of wilful murder nor even of manslaughter is sustainable on the basis of surviving evidence, a claim of contributory negligence certainly is.”

But the finger of blame is pointed firmly at Germany and its rulers. Diana Preston says none of the justifications given for sinking the Lusitania was valid under the international law of the time. It was a premeditated attack on a known target: “By firing without warning, Schwieger and those who despatched him were guilty by the standards of 1915 of ‘wilful murder.”

In the longer run, the attack proved to be a spectacular ‘own goal’ for Germany. When unrestricted U-boat warfare was resumed in 1917, ‘Remember the Lusitania’ became a rallying cry for Americans entering the First World War.