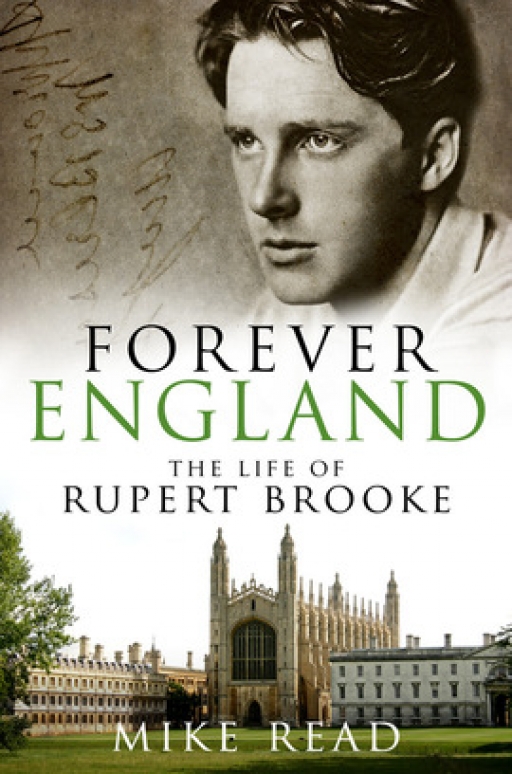

Publisher’s Description:

‘Rupert Brooke, strikingly good-looking, e ffortlessly charming and prodigiously gifted, has become the tragic embodiment of the generation lost between 1914 and 1918. Upon the poet’s tragic untimely death, Winston Churchill declared that ‘we shall never see his like again’.

Brooke died serving king and country on the anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, St George’s Day 1915, en route to fight at Gallipoli. As the tributes poured in and the war gathered momentum, the press heralded him as a hero – a focal point for the nation’s grief.

Already an acclaimed poet and dramatist in his youth, his romantic war poetry contrasts starkly with the work of some of his more disillusioned contemporaries. But the private letters of ‘the handsomest man in all of England’ reveal a far more troubled, and often misunderstood, individual…

In this updated edition of Forever England, Mike Read, founder of the Rupert Brooke Society, explores the poet’s fascinating life and legacy. From a tangled web of secret a ffairs, literary circles, mental illness and a previously unknown lovechild emerges the intriguing personality and enduring poetry of Rupert Brooke – the voice of a country torn apart by war.’

Centenary News Review:

Review by: Eleanor Baggley, Centenary News Books Editor

As Rupert Brooke prophesied in his sonnet ‘The Soldier’, there is now a ‘corner of a foreign field/ That is forever England’ on the Greek island of Skyros. On April 23rd 1915, on his way to fight in the Gallipoli campaign, Brooke died from sepsis resulting from a mosquito bite. Mike Read’s biography, Forever England, which has been updated for the anniversary of his death, aims to reveal the man behind the poems by exploring his life and legacy.

As a poet Rupert Brooke has been both lauded and condemned in equal measure. Unlike his contemporaries, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, very few details about Brooke’s life have become general knowledge.

Brooke’s striking good looks and reputation as the ‘handsomest man in all of England’ is perhaps the most well-known fact about his character. Frances Darwin, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, called him a ‘young Apollo, golden haired’. This comparison would later feed into the Brooke myth that gathered momentum after his death in 1915.

The word that best describes Brooke is exuberance. He grew up rubbing shoulders with the likes of the Stephen sisters (later to become Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf) and Lytton Strachey. He attended Rugby school and later Cambridge, becoming heavily involved in writing, theatre and sports. He also had several passionate love affairs and, at twenty, fell in love with the fifteen year old Noel Olivier. Brooke and Olivier later became engaged, but their relationships was rocky and fell apart. Nevertheless, they remained in contact until his death.

Although Brooke’s life can be defined by a youthful exuberance, Read delves deeper and reveals the secret worries, sadness and hypersensitivity that lay just below the surface. By looking behind the mask, Read opens up new layers of meaning in Brooke’s poetry.

Brooke’s war poetry has been criticised for its lack of depth and its idealised version of war. His five war sonnets entitled ‘Nineteen Fourteen’ certainly demonstrate this, though their lyricism is often overlooked. Unfortunately, whilst this biography does attempt to reveal the man behind the myth, on the whole it continues to feed into the hero worship without addressing it critically or constructively. Significantly the biography is missing what, in my opinion, is a key poem in Brooke’s oeuvre: ‘Fragment’ written in April 1915 shortly before his death. This later poem hints at a change in direction for his poetry and possibly a change in his opinion of war.

At times reading this biography there is a sense that Read was intent on including all his research in the book which, although frequently fascinating, was all too often infuriatingly tangential. We learn details that are irrelevant to the subject in hand and which add little to the reader’s understanding of Brooke as a person and a poet. For a biography written by the founder of the Rupert Brooke Society it initially showed promise, but a lack of depth and worthwhile detail resulted in an overall dissatisfactory reading experience. Read skims the surface of Brooke’s life, giving us all the places, dates and people, but somehow not quite transferring his personality to the page.

As a whistle stop tour through Brooke’s life and perhaps a gentle introduction to the man behind some of the most famous poetry of the first world war, Forever England is an enlightening read. Quotes from Brooke’s correspondence with friends and lovers and extensive quoting of his poems, ranging from his early teenage attempts to his war sonnets, make for lively reading. For a more comprehensive study of Brooke, however, it may be worth looking elsewhere.

What do you think about this book or review? Please add a comment below.