Publisher’s Description:

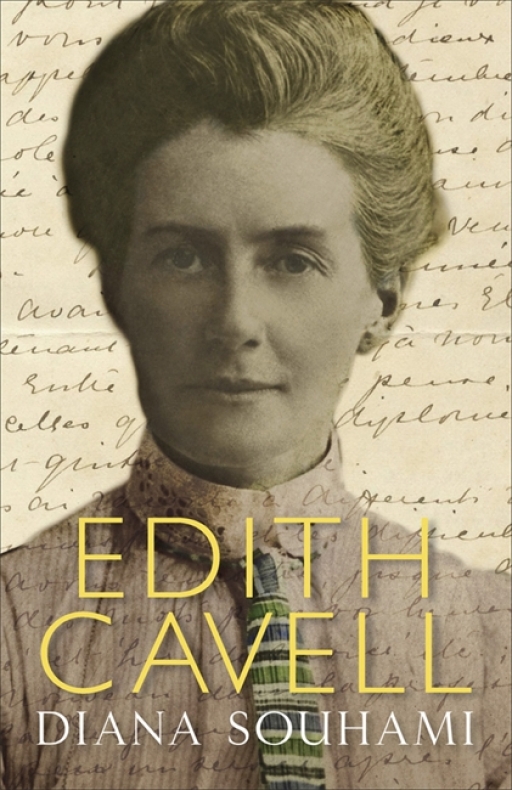

‘Edith Cavell was born in 1865, daughter of a Norfolk vicar, and shot in Brussels on 12 October 1915 by the Germans for sheltering British and French soldiers and helping them escape over the Belgian border.

Following a traditional village childhood in 19th century England, Edith worked as a governess in the UK and abroad, before training as a nurse in London in 1895. To Edith, nursing was a duty, a vocation, but above all a service. By 1907, she had travelled most of Europe and become matron of her own hospital in Belgium, where, under her leadership, a ramshackle hospital with few staff and little organization became a model nursing school.

When war broke out, Edith helped soldiers to escape the war by giving them jobs in her hospital, finding clothing and organizing safe passage into Holland. In all, she assisted over two hundred men. When her secret work was discovered, Edith was put on trial and sentenced to death by firing squad. She uttered only 130 words in her defence. A devout Christian, the evening before her death, she asked to be remembered as a nurse, not a hero or a martyr, and prayed to be fit for heaven. When news of Edith’s death reached Britain, army recruitment doubled.

Diana Souhami brings one of the Great War’s finest heroes to life in this biography of a hardworking, courageous and independent woman.’

Centenary News Review:

Review by: Eleanor Baggley, Centenary News Books Editor

At dawn on Tuesday 12th October 1915 Edith Cavell faced a firing squad of German soldiers, for ‘treason committed in time of war (for having led recruits to the enemy)’. She had only been sentenced the day before.

Edith Cavell, the daughter of a vicar, grew up in a small village in Norfolk. She spent some years as a governess in both England and Belgium before confiding to her cousin that ‘someday, somehow, I am going to do something useful. I don’t know what that will be. I only know that it will be something for people.’ Then, in December 1895, Cavell applied for any vacancy in London for an Assistant Nurse Class II.

Cavell’s training and the beginning of her nursing career was unremarkable and difficult. Though polite, kind and caring, she had not completely won over her matron, Eva Luckes, who thought she was ‘very self-opinionated…Her manner was partly due to shyness partly to deceit’. Nevertheless, Luckes did support her throughout her career and often advised her. In 1907, after years of hard work and trying and failing to get a senior nursing post, Cavell was asked by a leading Brussels surgeon, Dr Antoine Depage, if she would become the matron of the first training school for nurses to be opened in October of that year. Cavell agreed and left for Brussels in August.

In late July 1914, whilst the prospect of war grew ever closer, Cavell was having a well-earned holiday visiting her family at home in Norfolk. On 1st August she received a telegram from one of the sisters in Brussels asking if she would be able to return with the threat of war so close. Cavell quickly packed her belongings and arrived in Belgium in the early hours of Monday 3rd August. After the German’s marched into Brussels she spoke to her nurses and insisted, not for the first time in her career, that nursing knew no frontiers. Her nurses would treat any wounded soldier, whether friend or foe – their work was for humanity. It was this simple goal – to help other people, no matter who they may be – that paved the way for Cavell’s role within the resistance network.

Souhami’s biography is perfectly arranged. Anything other than a chronological exploration of Cavell’s life wouldn’t quite come close to demonstrating how she went from a village in Norfolk to her premature death in Brussels. The chronological approach also allows Souhami to slow down time and focus in on the minutia of her last days. As we come closer to the execution, the chapters are split into the mornings, afternoons and evenings of the days leading up to it. Whilst this primarily provides us with a detailed account of Cavell’s last days and the attempts made or not made by various British and American officials, it also draws us into her narrative. These final chapters are well balanced – between the political side and Cavell’s personal experience – and hugely emotive.

The repercussions of Cavell’s death spread far and wide. In Britain she became a national hero and martyr, although this was the opposite of what she had sought by helping the resistance. To this day she is the only lone woman memorialised in Trafalgar Square. The statue is not without its contradictions however, as Souhami points out. On the one hand Cavell is remembered as the ultimate patriot and the statue is steeped in the language of patriotism; on the other hand her final words chiselled into the base act as a warning against blind patriotism. Those famous words – ‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone’ – were initially omitted from the statue as they were felt to question the integrity of war. In 1924, after a campaign from the National Council of Women of Great Britain and Ireland, Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald finally authorised the addition.

The imposing, modernist style statue of Cavell in the North East corner of Trafalgar Square is, for many, the only known legacy of her life and work. Souhami’s biography delves deeper into her life, thus revealing the woman behind the statue and securing her place within modern memory.

What do you think about this book or review? Please add a comment below.