On 26 June 1918 the US Marines’ fight for Belleau Wood finally came to an end, cleared of the last pockets of German resistance which had clung on in its northernmost reaches. The battle in this obscure wood 50 miles from Paris had become a focal point of American military hopes at the time, an early and vital display of the American Expeditionary Force’s capability on the battlefield. Patrick Gregory looks at the closing stages of the battle and at the special place it commands in the annals of US military history – and of the Marines in particular.

“Woods now US Marine Corps entirely”. It was a message which had taken three long weeks to become reality. When Major Maurice Shearer of 5th Marines was finally able to deliver it, it came as a great relief to his brigade commander James Harbord.

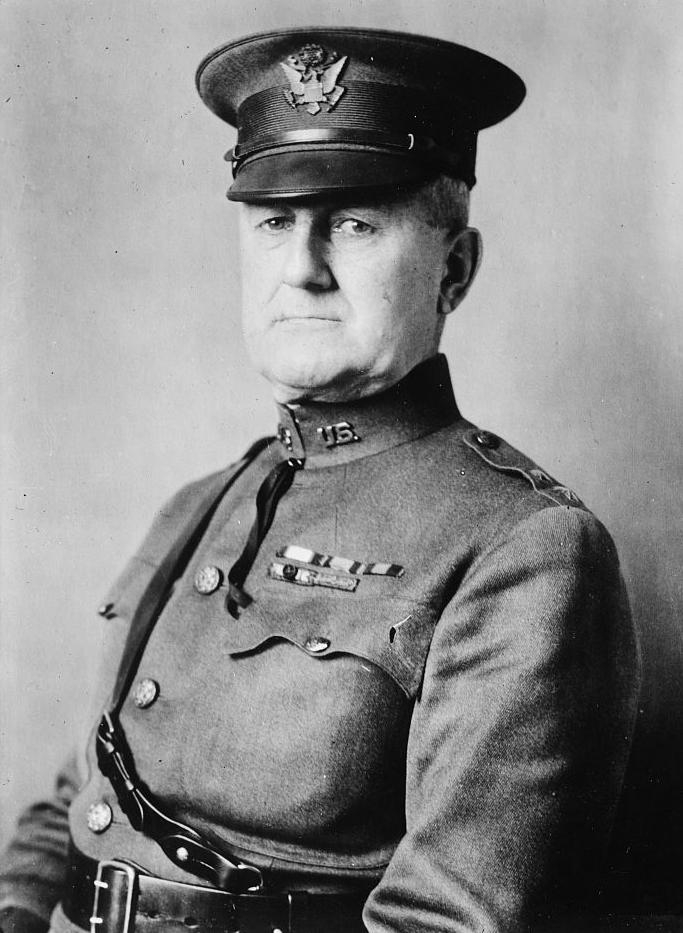

Major General James Harbord, pictured after the war (Image: Creative Commons/Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection)

Pershing’s former chief of staff had only taken charge of the 2nd Division’s Marine brigade the month before and these last weeks had been a trial by fire for him, pitched as he was into the high intensity of the battlefield.

In truth it had been a bloody encounter, marked by costly tactical errors in the battle’s early stages. Insufficient reconnaissance had been carried out before the first assault on 6 June and little artillery fire laid down before troops began their advance. The self-same battalion that were now closing the operation on 26 June – 3rd battalion of 5th Marines – had at that time walked into a hail of fire. Advancing on the wood in rank formation from the west through open wheat fields, they had been cut down with brutal ease by enemy machine gunners hidden inside. An attack by 6th marines from the south had fared little better. A grim casualty figure of 222 dead and over 850 wounded in the opening assault, rose further in the next two days as the Germans held their positions.

Different tactics and battalions had been employed thereafter, in different phases. Large scale firepower-led assaults began on 9/10 June, lasting several days. Headway was made, yet substantial pockets of resistance continued: enough to deter blind, mass attack in the dense undergrowth. The larger scale assault gave way on 13 June to smaller attacks aimed at taking out remaining machine gun nests, Harbord perhaps reluctant at this stage to risk a fresh bombardment of the wood, necessitating an evacuation beforehand of those areas they had already captured.

Threat

These smaller operations met with mixed fortunes, with intelligence patchy. The larger part of the wood was now in American hands yet the threat level posed by the enemy continued to elude them, their positioning and strength springing nasty surprises. In fact, German forces had continued to reinforce those sections of the forest they commanded and were well dug in.

A further shuffling of the pack saw 7th Infantry drafted in from the neighbouring 3rd Division. But thrown in at the deep end against a well-supplied and hidden enemy, the army regiment – whose first taste of battle this was – was outgunned. It sustained a large number of casualties in the few days it was invloved. Harbord was enraged. Seemingly unwilling to acknowledge the scale of the task he had handed the debutants, he denounced them to his own divisional commander Omar Bundy, saying that the “unreliable” regiment needed a “period of instruction” and the “weeding out” of inefficient officers.

So it was that 3rd battalion, 5th Marines found themselves back in the firing line for the last phase of fighting. Between 23 and 26 June they finished what they had begun three weeks before. A bombardment of heavy and light artillery, followed by ground operations finally broke the German resistance; and the closing days of fighting were savage indeed. Foot-by-foot the woodland fell, guns and grenades now giving way to bayonets and ‘toadstickers’, 8-inch triangular blades set on knuckle-handles. And finally, the message from Shearer: “Woods now US Marine Corps entirely”.

Some army units had been involved over the three weeks of the campaign, yet the battle had of course been a largely Marine affair. Certainly that is how it went down in military and Marine lore: the real beginning of the myth of the Marines.

As the story goes, German officers, in their battle reports, referred to the Marines as Teufelshunde “Devil Dogs”; and a journalist covering the conflict, Floyd Gibbons also helped, singling out one gunnery sergeant in dispatches as “Devil Dog Dan”. Either way, the name stuck. The Devil Dog would become a celebrated symbol of the Marines, and the image of the Marine as uncompromising warrior forged.

‘Devil Dog’ Fountain at Belleau Wood (Image: Creative Commons – image released by the United States Marine Corps with the ID 110607-M-YR678-1013)

The moss-covered “Devil Dog” fountain is located in Belleau, France, and symbolizes the spirit of the Marines who fought there in World War 1. The defeated Germans called the Marines Teufel Hunden, or “Dog from Hell,” and the Marine Corps took their new nickname with pride. The area was renamed to Bois de la Brigade de Marine to commemorate the Marines of 4th Brigade who stopped the Germans from entering Paris.

“It was the day the US Marines went from being a small force few people knew about to personifying elite status in the US military”, says Professor Andrew Wiest of the University of Southern Mississippi.

More significantly, and of strategic importance, the intervention at Belleau and that of the Marines’ 2nd and 3rd Division colleagues on the Marne had helped stop the German advance at a dangerous moment in the war for the Allies.

The commander of the US First Division Robert Lee Bullard would later declare: “The Marines didn’t win the war here. But they saved the Allies from defeat. Had they arrived a few hours later I think that would have been the beginning of the end. France could not have stood the loss of Paris.”

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18’ (The History Press) American on the Western Front & on Twitter @AmericanOnTheWF

© Centenary News & Patrick Gregory