The role of America’s volunteers is the subject of a new exhibition just opened at the American National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri.

It highlights the many contributions made by young men and women throughout the First World War and the immediate post-war period.

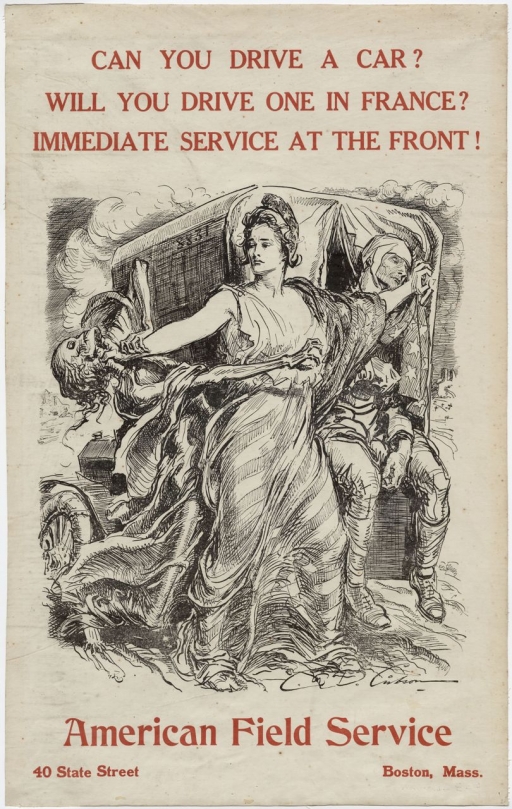

There are famous names associated with the time: Ernest Hemingway, E.E. Cummings, Gertrude Stein, and Walt Disney among them but The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919 presents individual descriptions, documents and artwork detailing the ways in which a wider array of Americans helped: national, regional and local groups throughout the U.S. such as the American Field Service, the YMCA and the YWCA who provided labour, food, entertainment and physical support to Allied forces.

Early volunteers

“One of the common narratives is that public opinion was very much one of neutrality prior to the United States’ entry into World War I,” says Senior Curator Doran Cart.

“While this is true to an extent, thousands of Americans did risk their lives and contributed to the war almost immediately at the onset. Through this exhibition, we share their incredible experiences.”

The efforts of the American Field Service are among those highlighted in the exhibition and the AFS organisation – still very much in existence – has opened its archives for the exhibition, sharing its photographs, stories and documents.

“The contributions of Americans during the early stages of war are not often given a proper spotlight,” says Museum President Matthew Naylor.

“By telling their stories, we also continue our mission of providing unique and compelling special exhibitions that educate the public about the continued effects of World War I”.

Patrick Gregory, co-author of ‘An American on the Western Front’, discusses how the US volunteer effort took shape

‘The world must be made safe for democracy……We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion’.

Woodrow Wilson was keen to focus on a nobler ideal for the American people to espouse as he addressed Congress in early April 1917. He was preparing both the politicians before him and the public at large for a war he had spent the better part of three years attempting to steer his country away from: one he now found unavoidable.

For his critics in the United States – among whom former president Theodore Roosevelt and the Preparedness Movement had been particularly vocal – Wilson’s declaration of war had come not a moment too soon. They had long argued that German aggression had to be confronted head on by more active means than mere financial support and trading help, as vital as that was.

US volunteer ammunition truck driver Ned Henschel from Missouri (Image: National World War I Museum & Memorial)

Yet there was a legion of Americans who had been active in Europe since had broken out in the summer of 1914 – volunteers and participants who had been drawn into the fray by what they saw as a ‘righteous’ cause.

Some of them had ties of family or friendship with France or Britain, others had found themselves in Europe at the beginning of the war as an accident of timing and travel plans. Either way, they had fetched up in Paris offering their services in whatever manner would be deemed most useful: first in ones and twos, and then on a more organised basis, reporting to hospitals and military offices and American expatriate organisations, one of the first major encounters of the war, the first Battle of the Marne in September 1914, acting as a notable early recruiting sergeant.

The volunteer effort soon took shape, aiding increasingly in the task of evacuating military wounded from the front, and by the tail-end of 1914 into 1915 three distinctive ambulance groupings began to emerge: the Harjes Formation – named after the senior partner of the Morgan-Harjes Bank in Paris – and the second, Richard Norton’s Anglo-American corps.

These developed separately and worked as distinct units for over a year before eventually merging under the banner of the American Red Cross. But it was a third ambulance grouping spawned by the American Military Hospital in Paris’ Neuilly suburbs, which would grow into the largest and best organised: the American Field Service.

By the time war was declared in 1917 between two and three thousand young Americans were already on the front line, attached to French army units as ambulance and truck drivers. Still others were engaged as actual combatants: American members of the French Foreign Legion and most famously – and glamorously – the pilots of the Lafayette Escadrille and the Lafayette Flying Corps.

(Read Patrick Gregory’s full article in CN features)

The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919, located in Memory Hall at the National World War I Museum, runs until October 2nd 2016. It will then travel to other institutions. In April, the Museum also launches a supplemental online version of the exhibition to provide an interactive experience featuring additional photos and stories from American volunteers. Principal funding for the exhibition was provided by the Florence Gould Foundation.

Exhibition images & event information supplied by National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of An American on the Western Front: The Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber – to be published in July 2016