A centennial exhibition exploring the dramatic events of 1917 that reshaped America’s role in the world has opened at the National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia.

It looks at the fundamental political and cultural changes brought about by US entry into the First World War, Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution and the Balfour Declaration – Britain’s expression of support for a Jewish national home in Palestine.

1917 is presented ‘through the eyes of American Jews, who reacted to these events both as Americans and as part of an international diaspora community,’ NMAJH says.

“The conflicts and consequences of 1917 are often overshadowed by later events, but they determined so much about the American and Jewish experiences thereafter,” said Josh Perelman, Chief Curator and Director of Exhibitions & Collections.

“While the exhibition is anchored in the past, it has powerful relevance to contemporary issues we are facing today, as a nation and as individuals.”

More than 120 artefacts have been assembled for the exhibition, which will also travel to New York later this year for display by its co-organisers, the American Jewish Historical Society.

The exhibits include an original draft of the Balfour Declaration, being displayed in the US for the first time; a copy of the Treaty of Versailles; and a letter from Soviet Foreign Affairs Commissar Leon Trotsky, constituting America’s first formal notification of the establishment of the Soviet Union.

There’s also a decoded copy of the Zimmermann telegram, Germany’s offer of a military alliance to Mexico in January 1917 which influenced President Woodrow Wilson’s decision to enter the Great War three months later.

Jacob Lavin (centre), was one of the American Jews who fought in World War I. He’s pictured with a group from the American Expeditionary Forces in France (Photo: National Museum of American Jewish History: Gift of Marilyn Lavin Tarr -1996.51.5)

Nearly 250,000 Jews joined the US armed forces, among them William Shemin, posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, America’s highest bravery decoration, in 2015 for his heroic actions in France during WW1.

But although many immigrant communities expressed their patriotism in the military and on the home front, the exhibition notes they still faced a political climate of increasing prejudice and suspicion.

NMAJH explains: ‘Beginning with the Immigration Act of 1917, the American government adopted increasingly strict laws limiting who could enter the country. This culminated with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which imposed strict immigration quotas and ended a remarkable period of immigration in American history.’

Of the Bolshevik Revolution, the museum says it ‘held out a brief hope that antisemitic regimes like that of the Russian Tsar would be swept away.’ But it also ‘unleashed forces of intolerance towards immigrants and minority groups.’

Although British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour expressed support for a Jewish national home in Palestine, in a letter written in November 1917, NMAJH notes that it ‘did little to address competing Arab and Jewish claims to the land.’

Leading US figures such as Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, whose robes are featured in the 1917 exhibition, voiced support for Zionism. “There is no inconsistency between loyalty to America and loyalty to Jewry,” he declared. But the museum points out that others expressed ambivalence over what it meant to support a nationalist project outside the United States.

‘These three events, the reactions that they triggered, and the conflicts they engendered set the stage for American policies throughout the 20th century and into the present’, NMAJH says.

‘1917: How One Year Changed the World’ is at the National Museum of American Jewish History, Philadelphia, until 16 July 2017. The museum will also be running public and education programmes. For more information, visit NMAJH. The exhibition transfers to the American Jewish Historical Society in New York, from September 1-December 29.

Source: National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH)

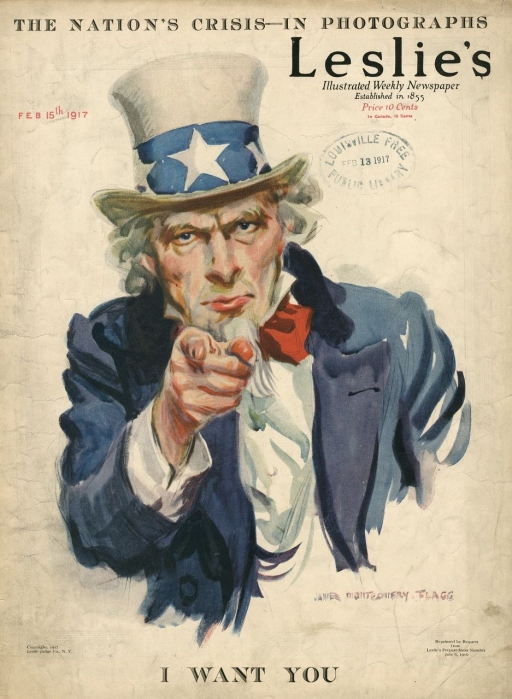

Images courtesy of NMAJH – Leslie’s Weekly illustration; Jacob Lavin – NMAJH, Gift of Marilyn Lavin Tarr 1996.51.5

Posted by CN Editorial Team