Inspired by the story of his grandfather and the Kashmir Rifles, Andrew Kerr discusses the gruelling East Africa campaign. Soldiers of the Maharajah of Kashmir’s army played a key role in forcing a battle with retreating German units on the Lukigura River on June 24th 1916.

Come the 1st July, attention on World War One will rightly focus on the Centenary of the Battle of the Somme. But a week beforehand, this is a fitting moment to reflect on the largely forgotten campaigns in East Africa. They like the Somme had their own horrors but of a different kind.

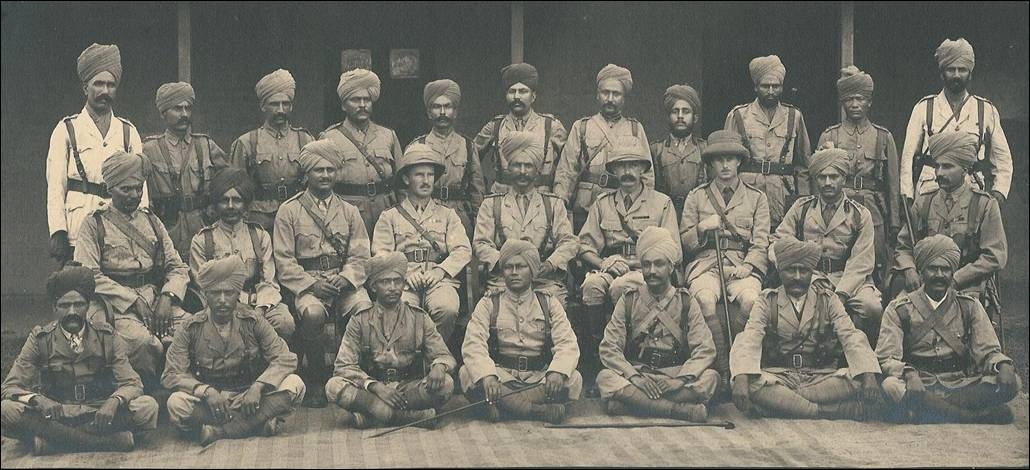

My journey of discovery started with the photograph (above) of some exhausted looking Indian soldiers from my Grandfather’s family photograph album – the uniforms were in shreds and as a former soldier myself I began to wonder what was this all about, what had happened? These investigations have taken me on travels to India, Kashmir, Kenya and Tanzania – I was even able to join the 2nd Battalion of the present-day Jammu and Kashmir Rifles on UN operations in Congo.

For those new to the subject, I am referring to a tropical bush war in what are today Kenya and Tanzania but were then the colonies of Imperial Britain and Germany. It had started as a few skirmishes or minor operations with the British and their troops faltering in the face of better trained, equipped and led German ‘Askari’ forces, organised into mobile field companies. However by the start of 1916 a major Allied force of some 27,000 men, many from South Africa, had been assembled near Mount Kilimanjaro under Lieutenant General Jan Smuts, with the purpose of invading German East Africa from the north.

Endurance

The war as a whole and the advance south in particular was an incredible test of human endurance. The tropical conditions coupled with a catastrophic failure to supply led to the disintegration of Smuts’ Army. Many units, most notably those from South Africa and Rhodesia, just melted away and had to be withdrawn from the theatre to recover after just a few months of the campaign.

Smuts’ strategy was to try to manoeuvre the retreating German force into a fixed battle where significant and dramatic attrition could take place. However the German Commander, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, had learnt key lessons earlier in the campaign at the Battle of Jasin in January 1915.

Losses of key German officers and the enormous expenditure of munitions, neither of which could be easily replaced given the stranglehold of the Royal Navy, prompted von Lettow-Vorbeck to develop a defensive strategy of withdrawal along prepared lines of communication with limited counter attacks.

Smuts had great energy and drive and he pushed his divisions forward with great speed, always urging them on in an effort to get behind and force a battle. This strategy only worked on a few occasions most notably at the Battle of Lukigura on 24th June 1916. The advance guard of the Kashmir Rifles were able to surprise and then assault with fixed bayonets the prepared German positions above the banks of the Lukigura River in present-day Tanzania.

2nd Battalion Kashmir Rifles – photographed at Satwari Camp, Jammu, on June 16th 1917 after returning from East Africa. Col Alec Kerr is in the middle row, fourth from left (Photo courtesy of Andrew Kerr)

The story of the private army of the Maharajah of Kashmir is told in my book about the soldiers of the Jammu and Kashmir Rifles. The title ‘I can never say enough about the men’ was taken from my grandfather’s own tribute to the endurance his forces. Lt Colonel Alec Kerr won the Military Cross for his leadership at Lukigura, and during the campaign.

The victory at Lukigura was something of a false dawn for the super human efforts of marching 400 km in six weeks in a roadless tropical jungle with near zero rations. The lack of clean water meant that most of the men had severe malaria and dysentery. The tsetse fly had also wiped out and killed all the horses and mules. The army and even Smuts himself were forced to halt and rest for a month.

Edward Paice in his book Tip and Run devotes a whole chapter to what he calls ‘the suicidal system of supply’, describing how almost every able-bodied male civilian was pressed into service as human porters on both sides. These men too found the tropical conditions and hardships too great. A vast number died leading Paice to state that this is one of the greatest and least known tragedies of the First World War.

The heroes of Lukigura, the 2nd Battalion Kashmir Rifles, continued to cheerfully endure the hardships in their typical and uncomplaining way. However the final head count at a medical board in January 1917 found just 20 men fit from a battalion tally of some 1,300. They too were returned home with their brothers from the 3rd Bn in May 1917. Back in Kashmir, even over a year later, British officers reported that many had not recovered.

The First World War experience in East Africa was so ghastly that Charles Duffy wrote in his book Through German Eyes – the British and the Somme (P49) that South African prisoners of war, presumably captured in the fighting at Delville Wood, stated that they would rather endure the winter in France than face the disease and hardship of campaigning in German East Africa.

The war in East Africa was as great a tragedy for its local peoples as the highly publicised Western and Eastern Fronts were to the Europeans. Here too total war brought famine, disease, social disintegration and misery.

Andrew Kerr is author of ‘I Can Never Say Enough about the Men: A History of the Jammu and Kashmir Rifles throughout their World War One East African Campaign’.

© Centenary News & Author

Images courtesy of Andrew Kerr ( from the collection of Lt Col A.N. Kerr)