Today marks exactly 100 years since the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28th June 1914.

Commemorative events are being held with a particular focus on the Bosnian capital, where the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra gives an early evening performance at the City Hall.

Franz Ferdinand was shot dead shortly after leaving a reception at the building in 1914.

The programme features music by Haydn, Schubert, Berg, Brahms, Beethoven and Ravel – composers drawn from the former belligerent countries, Austria, Germany and France.

The concert will be relayed on a large screen outside City Hall, and is being transmitted to television and radio stations worldwide by the European Broadcasting Union.

It can be heard live on BBC Radio 3 at 5pm.

Two new exhibitions open in Sarajevo on 28th June 2014; a photographic exhibition entitled Making Peace and at the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an exhibition called The Dignity of Mankind.

Gavrilo Princip

Centenary News’ Editor, Nigel Dacre, is in Sarajevo this weekend and filing from the city.

As he reported yesterday (June 27), politicians from the predominantly Serb-populated Republika Srpska, one of the two administrative entities that make up Bosnia and Herzegovina, have unveiled a controversial statue of Franz Ferdinand’s killer, Gavrilo Princip.

Museums, embassies and other institutions around the world are marking the Centenary.

In Austria, the Museum of Military History of Vienna is exhibiting one of the guns used in the assassination, alongside the car carrying the Archduke when he was shot and the blood-stained shirt he was wearing.

Museums, including America’s National World War I Museum, are holding a special ‘day of observance’, which will see events, talks and official ceremonies take place to commemorate the Centenary of the assassination.

At sea, ships are urged to fly flags or ensigns at half-mast in a call for peace and reconciliation organised by UNESCO, the United Nations scientific and cultural agency.

Ships in harbour are asked to sound a signal of remembrance at the same time worldwide – 17.00 GMT.

UNESCO is also holding a commemorative ceremony on the Belgian coast after a conference in Bruges aimed at strengthening international efforts to protect the wrecks of ships sunk in the First World War.

Serbia’s President, Tomislav Nikoli, was expected to attend commemorations in Sarajevo today, but announced earlier this month that he could not be in an environment where the Serbian people were being “accused” of aggression.

He was referring to Sarajevo’s recently restored town hall, where a sign hangs criticising Serbia for its actions in the Bosnian War of the 1990s.

The Serbian Prime Minister, Aleksandar Vucic, supported the President’s move, stating that he personally “cannot stand next to a sign describing Serbia as a facist aggressor”.

The Assassination

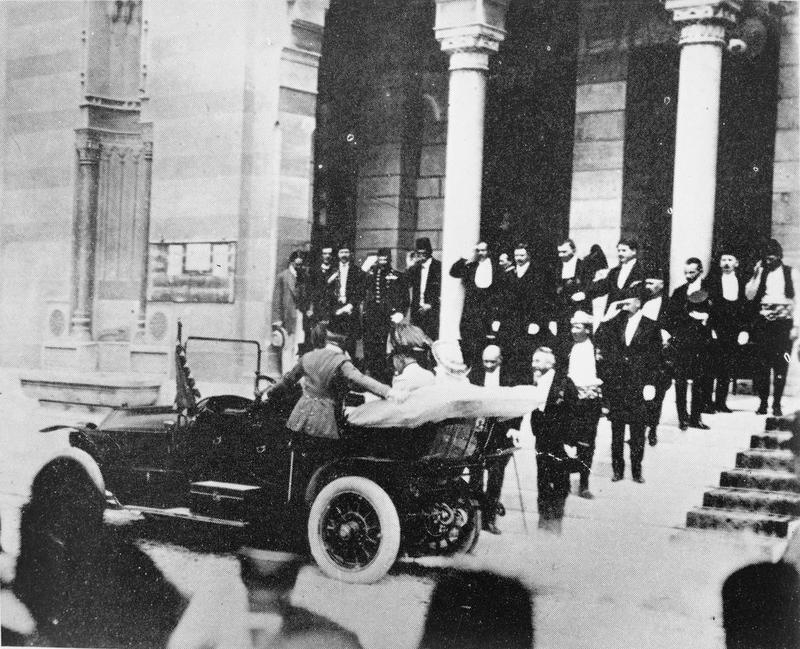

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, departing from City Hall, Sarajevo, shortly before they were assassinated © Imperial War Museum (Q91848)

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, departing from City Hall, Sarajevo, shortly before they were assassinated © Imperial War Museum (Q91848)

Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, was murdered with his wife Sophie as they drove through the streets of Sarajevo – then a part of the Austrian empire.

A group of Bosnian-Serb assassins had kept track of the Archduke’s movements in the city. After the Archduke’s driver took a wrong turn, Gavrilo Princip approached the car which was carrying the royals and fired his pistol. Franz Ferdinand and his wife died shortly afterwards.

The killers had been motivated by a desire to bring Austro-Hungarian rule over their people to an end. Debate remains as to what extent elements of the Serbian authorities – particularly in the intelligence community – were aware of the plot, and if they actively aided the assassins.

The Balkans – a politically and ethnically mixed area – had already suffered several regional conflicts in the twentieth century, but they had never drawn in the Great Powers the way they did in 1914.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination resulted in an ultimatum being delivered to Serbia by Austria-Hungary, which made a series of tough demands, including the suppression of anti-Austro-Hungarian propaganda. The majority of the demands were met, but Austria-Hungary declared war Serbia on 28th July 1914.

The intervening month between Franz Ferdinand’s assassination and the declaration of hostilities saw a flurry of diplomatic cables cross the European continent – the July Crisis.

Through a series of treaties over the years, two key blocs had emerged in Europe: the Entente of Britain, France and Russia; and the Central Powers, consisting of Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy.

Each nation’s own national and imperial interests have been fiercely debated among historians as to what extent they were responsible for a local conflict spiralling into a world war.

Russia mobilises

Russia considered itself the protector of the Slav people and the defender of Serbia. It would not allow Austria-Hungary to march unopposed and Russia began to mobilise itself.

This mobilisation alarmed Germany, which also began to prepare its troops. Meanwhile, Berlin had promised Vienna a ‘blank cheque’ – or unconditional support for whatever action Austria-Hungary decided to take against Serbia – an action considered by some historians as crucial to spurring on Vienna’s invasion.

In Western Europe, Britain eyed Germany – a burgeoning naval power, with the largest army in Europe and growing industrial capabilities – with caution and a certain amount of apprehension. France, still reeling from the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany during the war of 1870-71, also remained cautious of its neighbour.

Although it should be remembered that not all historians agree that war was inevitable in the summer of 1914, the assassination of the Archduke is often referred to as ‘the spark that lit the fuse’ in Europe.

Images courtesy of the Austrian National Library; Imperial War Museum

Posted by: Daniel Barry, Centenary News