As cross-channel commemorations get under way, Centenary News reports from the Flanders coast on Britain’s daring attempt to stifle the German submarine threat at a critical moment in the First World War.

In the spring of 1918, an armada of more than 70 warships sailed to attack the heavily fortified harbours of Zeebrugge and Ostend, in one of the Royal Navy’s boldest undertakings of WW1.

Several of those ships were intended never to return. Instead, they were filled with concrete, with the aim of sinking them to block the channels used by German U-boats to reach the open sea.

After delays caused by the weather, the operation finally got under way on the night of April 22/23. The significance of the date wasn’t lost on Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes, the driving force behind the Zeebrugge Raid. “St George for England” he signalled, as his forces prepared for battle on the feast day of England’s patron saint.

Captain Alfred Carpenter, tasked with put a landing party ashore from the cruiser HMS Vindictive, signalled back: “May we give the dragon’s tail a damn good twist.”

The action at Zeebrugge, starting at just after midnight on April 23, lasted little more than an hour. And although ultimately unsuccessful, the British view of it as a triumph was reflected in the awards of many decorations, including eight Victoria Crosses.

HMS Vindictive’s diversionary assault – aimed at knocking out German gun emplacements on the harbour wall, or Mole, while the blockships reached their positions – soon ran into trouble.

The wind changed, exposing the sailors and Royal Marines to heavy fire as they lost their protective smokescreen. And in a strong current, they struggled to get onto the breakwater as Vindictive manoeuvred alongside with two ferries, Daffodil and Iris II. They’d been requistioned from the River Mersey because of their suitability for operating in shallow waters.

Closer to shore, the Royal Navy succeeded in wedging an obsolete submarine, HMS C.3, between the piers of a viaduct, then blowing it up to cut off the German defenders on the Mole.

Aerial view of HMS Thetis, HMS Intrepid and HMS Iphigenia sunk in the mouth of the Bruges Canal at Zeebrugge (Photo © IWM Q 49164)

But what of the main objective – the sinking of the blockships to deny U-boats access to the North Sea from the canal linking their inland base at Bruges with the Flanders coast at Zeebrugge?

HMS Thetis, had to be scuttled short of the canal mouth after fouling a propeller. The two others, HMS Intrepid and HMS Iphgenia, were sunk across the channel but they didn’t obstruct it entirely. The first U-boat slipped past at high tide just two days later. The Germans then removed part of the harbour wall to widen the canal. And after dredging, the submarines could pass as before.

Casualty estimates vary, but British losses are put at more than 200 dead and around 380 wounded, much heavier than the German casualties of some 10 killed and 16 wounded.

The simultaneous raid on Ostend also failed – together with another attempt there in May, this time using HMS Vindictive as the blockship. The cruiser’s bow is today preserved as a memorial on the harbour front at Ostend, close to where it was sunk.

Captain Alfred Carpenter was among the recipients of the VC, nominated by fellow officers for his command of HMS Vindictive under fire. His citation reads: “He showed most conspicuous bravery, and did much to encourage similar behaviour on the part of the crew, supervising the landing from the Vindictive on to the Mole, and walking round the decks directing operations and encouraging the men in the most dangerous and exposed positions.”

Gun emplacements on the Zeebrugge Mole. The Flanders coast was also heavy defended with shore batteries and bunkers (Photo © Tomas Termote)

The commander of the submarine HMS C.3, Lieutenant Richard Sandford, also received the VC. He died in hospital of typhoid fever, aged 27, twelve days after the signing of the Armistice in November 1918.

Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes, who’d already made a name for himself during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, was promptly knighted.

In Flanders, the events of St George’s Day 1918 are commemorated in street names such as Admiraal Keyesplein – Admiral Keyes Square – in Zeebrugge, and Vindictivelaan – Vindictive Street – on the harbour front at Ostend.

After repairs, Daffodil and Iris II returned to ferry duties on the Mersey between Liverpool and Wallasey.

Sir Roger Keyes is commemorated at Zeebrugge with this monument, in Admiraal Keyesplein, made of two concrete blocks from the original Mole (Photo: Centenary News)

Assessment

Winston Churchill, who was the minister responsible for the Royal Navy at the start of WW1, said of the Zeebrugge Raid: “It may well rank as the finest feat of arms in the Great War.”

Looking back now, it’s generally accepted the attacks didn’t deliver on penning up the Flanders U-boat fleet. But they were an important morale boost for Britain at a critical moment in the Great War. Only two weeks before St George’s Day, Field Marshal Haig had warned of ‘backs to the wall’ in the land campaign as the German Army once more pushed towards Ypres and the Channel ports.

Among guests attending the centenary commemorations in Belgium is Nick Jellicoe, grandson of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, who was commander of the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland, and later professional head of the Royal Navy as First Sea Lord before his dismissal in December 1917.

Admiral Jellicoe had himself warned that Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 threatened threated Britain’s very survival in the war.

100 years on, his grandson offered this assesment. Speaking at the opening of the Battle for the North Sea centenary exhibition in Bruges, he said: “The raid on Zeebrugge was an extraordinary feat, hailed in Britain, winning 11 Victoria Crosses. There’s no question of the courage but it was questionable in its tactical efficacy.”

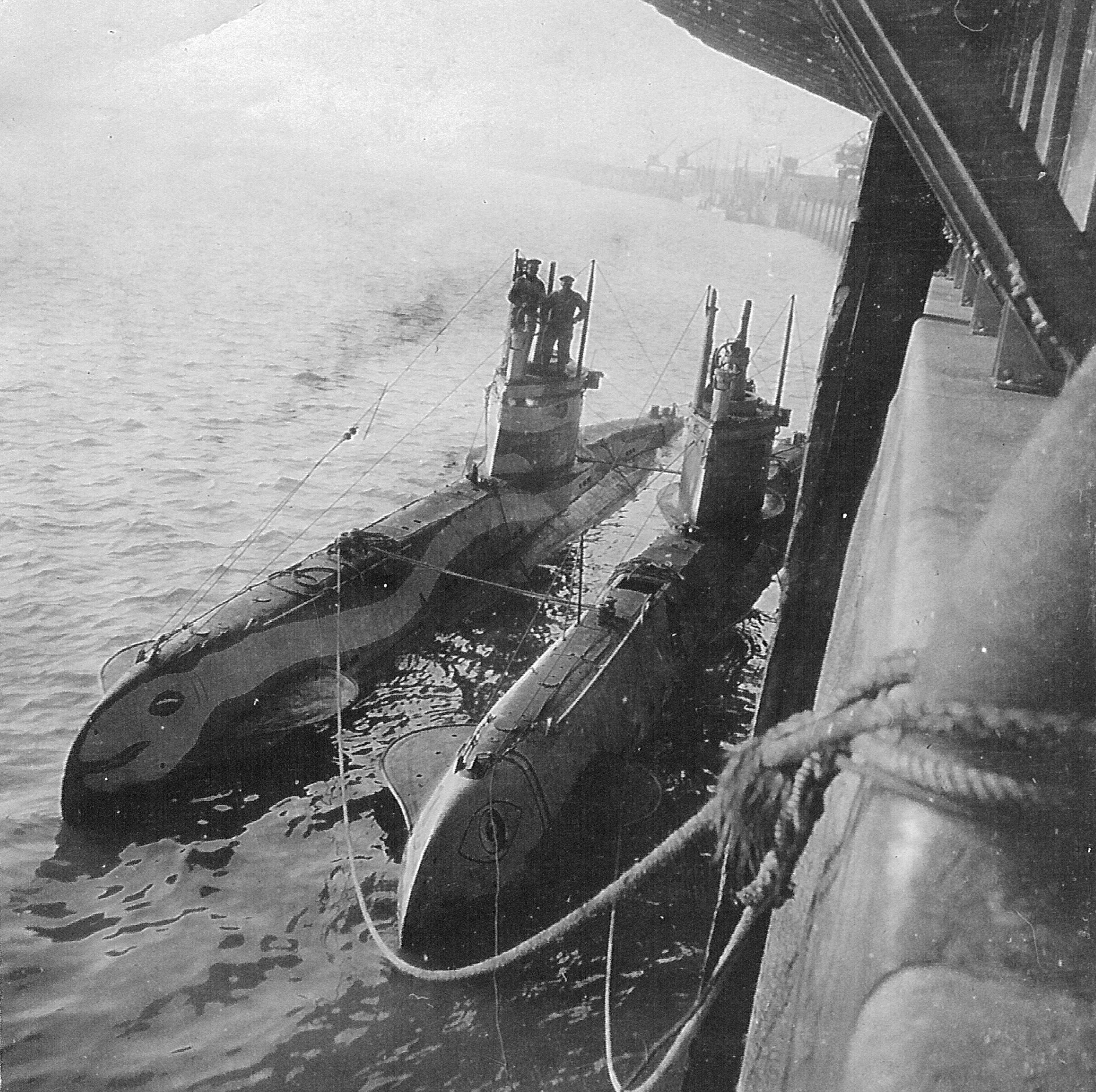

German submarines UB-10 and UB-13 berthed alongside the Zeebrugge Mole (Photo © Tomas Termote)

Centenary News will be reporting on the international commemorations taking place in Flanders this weekend – including the opening of ‘The Battle for the North Sea’ exhibition in Bruges, curated by marine archaeologist Tomas Termote, where all 11 Victoria Crosses have been united for display. We will also be covering remembrance events in Dover on Monday April 23, the 100th anniversary of the raid.

A remembrance service and parade will be held in the Wirral on Sunday, April 22, to commemorate the part played by the ferries, Daffodil and Iris II.

Images courtesy of Imperial War Museums, © IWM Q 49164 (Zeebrugge aerial view); Tomas Termote (Zeebrugge Mole & submarines UB-10, UB-13); Centenary News (HMS Vindictive Monument, Keyes memorial)

Posted by CN Editor, reporting from Zeebrugge

Sources: Visitflanders, Dover Town Council, Wirral Council, IWM Lives of the First World War, Wikipedia/various