The Canadian doctor, soldier and poet who wrote ‘In Flanders Fields’ died on 28 January 1918 after falling ill in France. Author Chris Dickon reflects on Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae’s life and legacy.

It would not be until the time of the Armistice in November 1918 that one of the most enduring poems of the just concluded First World War would become widely read in the United States and Europe. It had been written on the Ypres battlefield in 1915, and its author, Dr John McCrae, had died of pneumonia and meningitis on 28 January 1918. He had long since been buried in the communal cemetery at Wimereux, France.

The story of the writing and publication of his poem, In Flanders Fields, is told in various contradictory versions, some of them more interesting than others. But the story of John McCrae himself is that of a solid, kind and thoughtful man, an animal lover who was known to always have a dog or horse at his side, strong and straightforward in his conduct of war.

Surgeon

Born near Guelph, Ontario on 30 November 1872, he had started writing poetry as a child, though none of it would match the eventual acclaim of his inspiration at Ypres. With training in Canada, the United States and United Kingdom, he became a surgeon, and he knew death. He had performed more than 400 autopsies as a pathologist at McGill University in Montreal, was published in the medical journals of the day, and had been forever affected by the death of a child in his care during time at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Maryland.

Concurrent military training took McCrae to the Second Boer War of 1899 -1902, and returned him to service as a Major in the Canadian Field Artillery in World War I. Though he would have preferred to stay in battle, he was assigned after Ypres to set up a Canadian general hospital near Boulogne-sur-Mer, where he died 100 years ago in 1918.

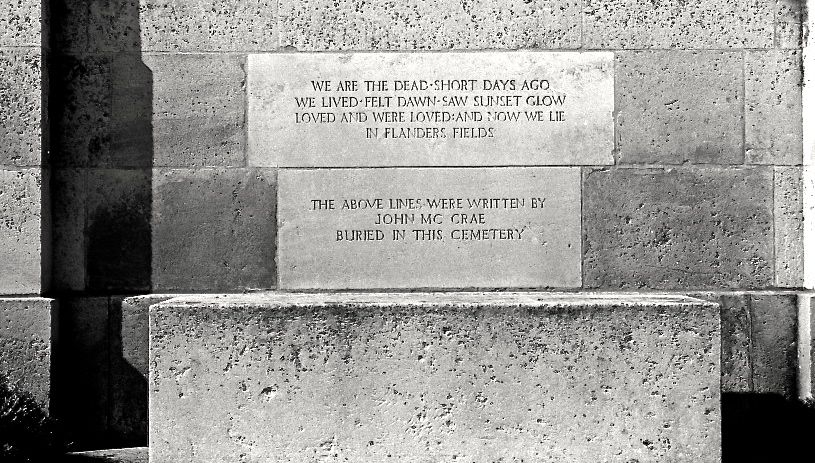

A memorial seat, inscribed with lines from ‘In Flanders Fields’ at CWGC Wimereux Communal Cemetery, Dr John McCrae’s last resting place (Photo: Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

One version of the story of his signal poem is that of a creation of the moment quickly abandoned by its author and nearly lost. In that telling, he had just buried a friend (a student of his at McGill) under cover of the darkness of the night, then sat in an ambulance overlooking the battlefield and wrote the poem straight through. Then, reading it back to himself, he decided it was not very good, balled it up and threw it in a wastebasket, from which it was rescued by an observer and sent to Punch magazine in London, where it was published anonymously.

Other versions of the story tell of McCrae’s own sending of the labored-over poem to Punch after it had been rejected by The Spectator of London, and the delivery of worldwide acclaim when his identity was discovered soon thereafter.

Whatever the truth of the matter, In Flanders Fields became itself an active participant in the war effort of the time and in the consideration of war in the future. It was quickly used to recruit soldiers and sell war bonds. Then, at the time of the war’s end, it was published in the American magazine Ladies Home Journal, which accelerated its effect into the following decades and until the present time.

Timeless

It was the poem’s imagery of red poppies that would give it a timeless effect. Poppies had been associated with war going back to mythology. Their opium derivatives had been associated with the Trojan wars, and it was believed that they seemed to grow in profusion in battlefield cemeteries as an expression of the blood of the dead. With the publication of the poem, they eventually became the symbols of the mortal and physical sacrifice of war.

In the United States, the determination of Moina Michael, a war secretary for the YMCA of New York City, led to the adoption of the red poppy as a symbol of remembrance by the American Legion in 1920. In France, Anna Guerin of the French YMCA led a similar movement to the allied nations of the war, extending as far as New Zealand. The small cloth or paper recreation of the red poppy with green stem became the symbol of the British Legion Remembrance Day in 1921.

John McCrae’s grave at Wimereux Communal Cemetery (Photo: Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

John McCrae’s grave at Wimereux Communal Cemetery (Photo: Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

One hundred years after the death of John McCrae, the red poppies can still be found sold across the world on Remembrance or Veterans days, and still growing in many of the rural fields of Europe, seemingly on the strength of their own history. In Flanders Fields is still perhaps the most recited poem in the cemeteries of World War I.

Chris Dickon is author of The Foreign Burial of American War Dead, from which this is adapted, and the recent A Rendezvous with Death: Alan Seeger in Poetry, at War.

© Chris Dickon & Centenary News

Images courtesy of Library and Archives Canada C-046284 (John McCrae); Commonwealth War Graves Commission-CWGC (Wimereux memorial & grave)