A Royal Charter created the Imperial War Graves Commmission on 21st May 1917, to ensure that the British and Commonwealth dead of the Great War would be remembered forever.

Sir Fabian Ware, an eminent British Red Cross volunteer, was the driving force behind this mission. Yet the commission’s plans also provoked criticism when they were published at the close of 1918.

The cemeteries and memorials today honouring more than 1.7 million men and women who fell in both world wars are the legacy of Ware’s determination and vision.

Rudyard Kipling summed up his enterprise as ‘the biggest single bit of work since the Pharoahs.’

Apart from a change of name to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), continuity of remembrance has been the organisation’s hallmark, although much of its work was halted during the Second World War.

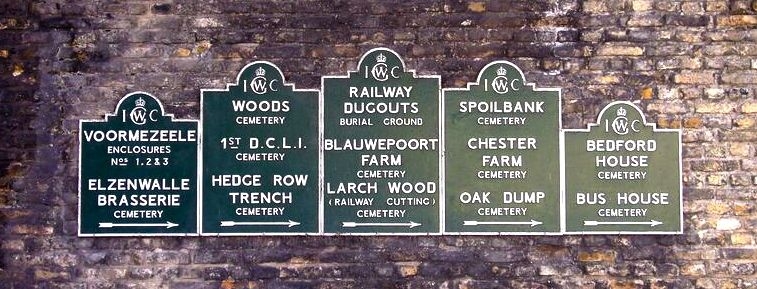

Imperial War Graves Commission direction signs, at the Lille Gate in Ypres (Photo: Centenary News)

Imperial War Graves Commission direction signs, at the Lille Gate in Ypres (Photo: Centenary News)

Fabian Ware, commander of a Red Cross mobile ambulance unit, began recording the graves of fallen soldiers in the early months of the First World War.

He was saddened by the sheer number of casualties he witnessed, and the lack of a plan to mark the final resting place of those killed.

By 1915, his work was recognised by the British government. The unit was incorporated into the Army as the Graves Registration Commission, with responsibility for finding, marking and registering British graves in France.

‘His vision chimed with the times,’ CWGC explains.

Ware was a former teacher, schools’ administrator, journalist and businessman with connections in government. Before the war, he’d edited The Morning Post, a national newspaper, for six years.

Attempting to enlist, aged 45, in August 1914, he was rejected as too old to fight.

‘Neither a soldier nor a politician, Ware was nevertheless well placed to respond to the public’s reaction to the enormous losses in the war,’ CWGC points out.

Previous British military practice had been to bury the dead in mass graves.

But as the architect Jeroen Geurst notes in his magisterial study* of Sir Edwin Lutyens’ Great War cemeteries: ‘Ware is one of the first who comes to realise that the next-of-kin of common soldiers will also wish to find their dear ones who have fallen.’

Crosses at Tyne Cot on the battlefields of Passchendaele, now the biggest Commonwealth Cemetery in the world (Photo: CWGC)

Crosses at Tyne Cot on the battlefields of Passchendaele, now the biggest Commonwealth Cemetery in the world (Photo: CWGC)

Peace was still a distant prospect when the idea of the Imperial War Graves Commission was born in 1917.

But Fabian Ware was concerned about the fate of the graves once the fighting was over.

With the support of the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VIII), he submitted a memorandum to the leaders of Britain and its Dominions calling for an organisation to reflect their combined sacrifice.

The Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) was founded by Royal Charter in May 1917 to provide for remembrance in perpetuity. In 1960, as Britain withdrew from empire, its name was changed to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The enormous task of recovering and identifying the dead started in earnest after the 1918 Armistice.

Three leading architects of the day, Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Reginald Blomfield, were commissioned to design the cemeteries and memorials that stand today as the most visible testament to the sacrifices of the First World War.

The Stone of Remembrance at Messines British Cemetery, Belgium (Photo: Centenary News)

The Stone of Remembrance at Messines British Cemetery, Belgium (Photo: Centenary News)

The equality of sacrifice was represented in the uniformity of the headstones, and although families were allowed to add personal inscriptions, no other distinctions were made for rank, race or creed.

Such principles are taken as read today, but in their time, they were highly controversial, and had to be vigorously promoted by the indomitable Fabian Ware. Some saw the IWGC’s stance as contrary to the freedoms fought for in the Great War.

It was the author and journalist Rudyard Kipling, who’d lost his only son John at Loos in 1915, who chose the inscription ‘Their Name Liveth for Evermore’ for the Stone of Remembrance, designed by Lutyens to commemorate ‘those of all faiths and none’.

100 years after the First World War, soldiers’ remains are still being discovered and identified, and reburied with full military honours.

Marking its own Centenary, CWGC gives an assurance that this work of commemoration will go on ‘today, tomorrow and forever’.

Far from the Western Front: Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery, Orkney (Photo: Centenary News)

Far from the Western Front: Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery, Orkney (Photo: Centenary News)

More information about the history and design of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s cemeteries can be found on the CWGC website.

Read more here about CWGC’s ‘For Then, For Now, Forever’ Centenary programme.

Also in Centenary News:

Review of CWGC Centenary exhibition at Brookwood Military Cemetery in the UK.

Sources: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

*Cemeteries of the Great War by Sir Edwin Lutyens p.13 – Jeroen Geurst, 010 Publishers Rotterdam, 2010

Images: CWGC (Tyne Cot archive); Centenary News

Posted by: CN Editor