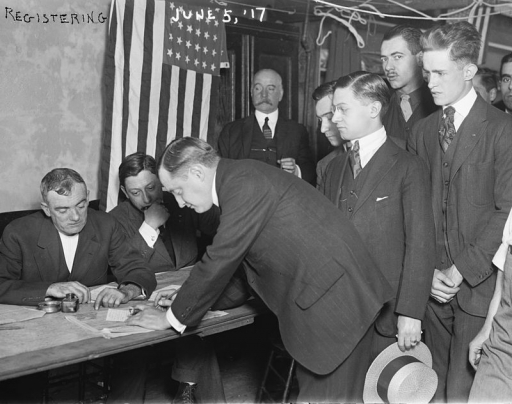

In June 1917, millions of American men went to their local draft boards the length and breadth of the United States to register their names under the Selective Service Act – the first step in a conscription process aimed at bolstering America’s meagre armed forces for the war in Europe. It was the first time conscription had been attempted in the US since the Civil War 50 years earlier, as CN’s Patrick Gregory explains

When America entered the Great War in the spring of 1917 its military manpower and combat readiness were a long way off the pace which would soon be demanded on the battlefields of the Western Front. The National Defence Act passed by the Wilson administration the previous year – itself a response to the demands of the Preparedness movement to boost the country’s armed forces – had aimed to raise army numbers to 165,000 and the National Guard to 450,000 over five years.

But a year on, troop numbers were still stubbornly low, little headway having been made. Only around 121,000 federal soldiers and 181,000 National Guard could readily be called upon, numbers hopelessly at odds with even the expectations of America’s own military planners in the General Staff.

President Woodrow Wilson had held discussions with the Secretary of War, Newton Baker, in preceding months to ask him to look at options for boosting these numbers as the threat of war loomed. General Pershing, en route with the first contingent of his American Expeditionary Force, had asked for one million men to be put at his disposal.

Committed

Wilson was committed to delivering the military manpower asked for, but he was instinctively opposed to the idea of outright conscription – possibly through the associations it held for him with the Civil War – and had thus far shied away from it. He held briefly to the hope that volunteerism might yet save the day but weeks into the war, seeing the gulf which existed between the number of troops available and those required, he abandoned his objections. The Selective Service Act was enacted.

Less than three weeks after its passage through Congress, the act was put into practice – ‘supervised decentralisation’ came into effect with 4,500-odd civilian draft boards ready to assess the young men sent before them.

All men aged between 21 and 30 were required as a first step to register for war service in their local precinct. Although mandatory to register, it was still not the case that these young men would automatically be pressed into service. A ‘draft’ of a certain number of men would have to be determined by means of a ballot – a next step which would begin six weeks later. Everyone registering on 5 June was allocated one of a series of numbers: when a subsequent lottery draw matched the numbers these young men were holding, they could be drafted; the first lottery was conducted by Baker himself on 20 July, wearing a white blindfold over his eyes.

A total of three drafts were made in the course of the war, both lowering and expanding the age range of those considered eligible for service from 18 to 45, resulting in a total registration of some 24 million men during the conflict, almost 25 per cent of the population of the country.

In turn, the draft enabled the United States to amass a total of around four million men in uniform by November 1918, two million in the field, a contribution affording America and her partners a substantial degree of fighting power and military reserve in the closing months of the First World War.

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18’ (The History Press 2016 – published in the US this April for the Centennial): American on the Western Front @AmericanOnTheWF.

Images: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection LC-DIG-ggbain-24572

Posted by: CN Editorial Team