Author: Jillian Davidson

As part of its centennial “In Flanders Fields Events”, Flanders House hosted a book presentation of Harlem’s Rattlers and the Great War (2014) in its Times Square, Manhattan office on November 17th.

In his remarks of welcome, Geert De Proost, General Representative of the Government of Flanders to the US, paid his respects not only to the bloody carnage in Flanders Fields during World War One, but also to the victims of Friday’s attack in Paris.

Quoting from Mona Michael’s poem “We Shall Keep Faith” (1918), a reprise to John McCrae’s poem of “In Flanders Fields” (1915), Geert De Proost promised that we too “shall keep the Faith with all who died.”

Publisher Hamilton Fish V introduced the event’s speaker, co-author of Harlem’s Rattlers, Professor Sammons.

Hamilton Fish V is also the grandson of Captain Hamilton Fish III, who played a leading role in the formation and deployment of the African American 369th Regiment.

Hamilton Fish V grew up on a highly romanticized and mythological version of the regiment, and claimed that it was not until forty years later, when “I met this great American historian, Professor Jeffrey Sammons of NYU,” that he discovered the Regiment’s more discerning story of bigotry and heroism.

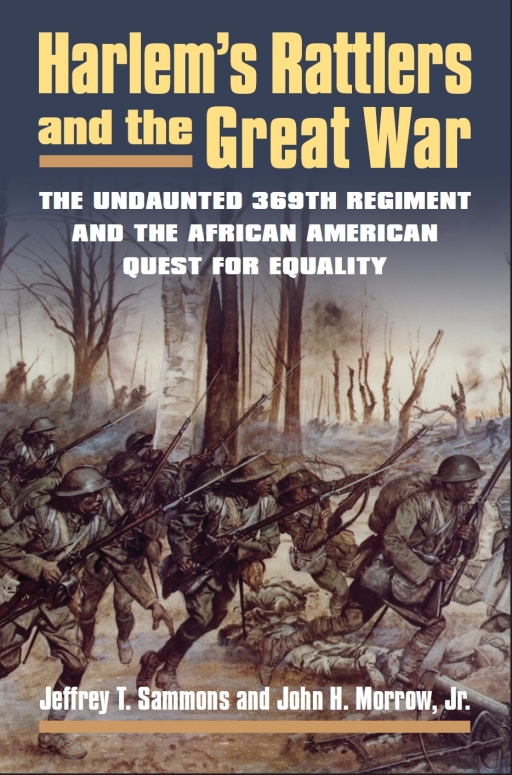

Sammons captivated a full audience with his history of New York’s African-American World War I combat unit. The 369th Regiment is most commonly known as Harlem’s Hellfighters, probably the name the American press gave the soldiers. Professors Jeffrey Sammons and John H. Morrow, Jr., however, preferred to recognize the name the soldiers themselves embraced.

The symbol of the rattlesnake recalled a quintessentially American icon from the Revolutionary War. It was associated with Benjamin Franklin’s attacks on the Crown and the Gadsden Flag with its words of warning, “Don’t tread on me.” By identifying themselves as Rattlesnakes, African- American soldiers declared that they were fighting for American democracy at home as much as abroad.

Out of respect for his venue, Professor Sammons recited song writer Andy Razaf’s rendition of “In Flanders Fields,” written in 1920. Its departures from the original highlighted the concern that though the fight in Europe was over, the fight for African Americans at home continued:

In Flanders fields where poppies blow,

Beneath the crosses, fow on row,

We blacks an endless vigil keep.

Yes, we, though dead, can never sleep–

Ingratitude made it so.

Why are we here? Why did we go

From loving homes that need us so?

Was it for naught we gave our lives,

On Flanders fields?

Ye blacks who live, to you we throw

The torch; be yours to face the foe

At home; and ever hold it high,

Fight for the things for which we die,

That we may sleep, where poppies grow,

In Flanders fields.

Towards the end of his talk, Sammons showed a wonderful video footage of the Victory Parade for the 369th Regiment that began at the Washington Square Arch and marched up Fifth Avenue all the way to Harlem. For seventy percent of the 369th, Harlem was home.

They marched in French formation, with sixteen men per row, which had never been seen before in America. “It was an impressive sight” which almost never happened, but for the intervening help of Herbert Hoover, head of the Commission for Relief in Belgium. “This parade ushered in the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro.”

In the video footage of the parade, Sammons pointed out Henry Johnson, the bravest of the brave Rattlers, who had to wait almost a century to receive his posthumous Medal of Honor on June 2nd, 2015. He thanked Caroline Wexselbaum, sitting in the audience, who, as a staffer for New York Senator Charles Schumer, tirelessly researched the first-hand documents necessary for securing long-overdue recognition for Harlem Rattlers’ most distinguished soldier.