Britain introduced transatlantic convoys in May 1917 to protect merchant ships from an increasingly dangerous German U-boat campaign. As Roger Hoefling explains, the move to escort merchant shipping on vital supply routes changed the outcome of the war.

On 6th August 1914, two days after Britain entered the First World War, ten U-boats of the Imperial German Navy began the first submarine war patrols in history.

Success soon came, U-21 sinking the Royal Navy light cruiser, HMS Pathfinder, on 5th September 1914. After more RN losses, on 21st October U-17 accounted for the SS Glitra, a cargo vessel, on passage from Grangemouth to Stavanger. For the first time, a submarine had sunk a merchant vessel, presaging what came very close to defeating Britain.

By 1913, so many had left farming for industry that Britain was having to import 80 per cent of its wheat and 50 per cent of its meat. Textile firms alone employed well over a million with most of their output going for export. Industry and more depended on imports as well, ore for 50 per cent of pig iron production coming from overseas, for example, while the Royal Navy’s newest ships were fuelled by imported oil.

In 1914, 43 per cent of the world’s merchant fleet, some 20 million tons gross, was owned and operated by Britain and the Dominions. These ships brought in food, raw materials, military supplies and troops while exporting industry’s output to the world and thereby helping fund the war effort.

Threat

Germany’s U-boat fleet was a momentous threat therefore to the unescorted ships of Britain’s Mercantile Marine. Indeed, until later in 1915 when, typically, a single stern-mounted 4.7″ gun for use against surfaced submarines gradually was introduced, they were also unarmed.

By February 1915, any illusion that the land war would be short had disappeared so the Imperial German Navy saw cutting the trade routes as the means to victory, expressed by Admiral Scheer, Commander-in-Chief of the High Seas Fleet, as ‘Our aim was to break the power of mighty England vested in her sea trade in spite of the protection which her powerful fleet could afford her.’

This resulted in Germany’s first period of unrestricted submarine warfare from 18th February 1915 whereby merchant ships, except for clearly neutral vessels, would be attacked without warning. This replaced the ‘cruiser’ or ‘prize rules’ requiring that crew and any passengers be allowed to take to a ship’s boats before it was sunk. The policy was suspended on 1st September 1915 however because of the USA’s objections in particular, heightened by the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7th May when American passengers were amongst those lost.

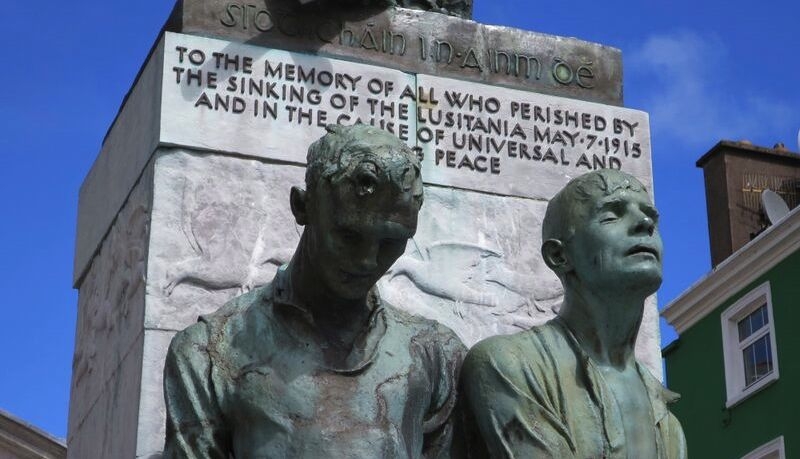

The Lusitania Memorial in Cobh, formerly Queenstown, Ireland (Photo: Centenary News)

The Lusitania Memorial in Cobh, formerly Queenstown, Ireland (Photo: Centenary News)

In Germany itself, the civilian population’s privation as the Royal Navy’s blockade increased its effect was becoming desperate. Coupled with military and political pressure, this led to unrestricted U-boat operations resuming on 1st February 1917.

With a daily average of 36 submarines at sea during the next three months, 44 on one day, Allied shipping losses reached a peak of 881,027 tons in April 1917. The previous record was 593,841 tons sunk in March. In short, one in four merchant ships leaving Britain was being lost to enemy action.

This brought the British Government’s realisation that starvation and more would force the country’s capitulation within six months.The shipbuilding and repair industry was unable to keep pace with the rate at which ships were being sunk.

The potential answer to the threat, the convoy system, was resisted by the Admiralty however. Albeit successfully used by the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic War of 1803-1815, it was dismissed as late as Jaunary 1917 in an Admiralty Staff Paper: ‘The system of several ships sailing together in a convoy is not recommended in any area where submarine attack is a possibility.’

Reluctance

Convoys, groups of merchant ships escorted by warships, were regarded as a defensive measure by the Admiralty which preferred the offensive role of patrolling the sea lanes.

It was thought too that a group of ships would be far easier to find than individual vessels; misunderstanding of ship movement statistics led to overestimating the number of naval escorts needed; merchant ship captains were thought incapable of the station-keeping that convoys demanded. Similarly, it was felt that ports could not cope with the simultaneous arrival of several vessels.

Spurred on by David Lloyd George after his appointment as British Prime Minister in December 1916, the Admiralty’s reluctance was eventually overcome. Troopships already had Royal Navy escorts, as did, from July 1916, merchant ships crossing between Harwich and the neutral Netherlands. From February 1917, RN ships accompanied those carrying coal from the south coast to France which had lost coalfields to German occupation. Further, convoys began between the Shetland Isles and Norway, also neutral, in April 1917.

Thus, ocean convoys finally were introduced in May 1917. The first sailed from Gibraltar for Britain on 10th May, 16 merchant ships being escorted by the Q-ships Mavis and Rule, armed vessels disguised as merchantmen, and initially by three armed yachts in addition. Arriving without incident, the convoy dispersed to west and south coast ports on 20th May. The other experimental convoy, 12 ships escorted by a Royal Navy cruiser, HMS Roxburgh, left the Hampton Roads in the USA on 24th May, reaching Britain on 8th June. Two vessels, unable to maintain speed, had dropped behind. One was torpedoed and sunk, the other arrived on 13th June

From that first success, by the end of 1917 the course of the war had been changed. That much still had to be achieved was evidenced by the imposition nationally of food rationing in mid-1918, this having been instituted first at a local level by such as the Bolton branch of the Co-op in Lancashire in August 1917.

© Roger Hoefling & Centenary News