Centenary News contributor Dan Hayes reports on the Zeppelin air raids that brought terror to London in 1915 and 1916.

At first glance the Dolphin pub in London’s Bloomsbury district is a seemingly average establishment, serving the usual array of beers and spirits and with a predictable array of lunchtime food.

Amid the bric a brac that decorates the Dolphin, however, there is a clock; its face brown and mottled and its hands forever stopped at 10.40pm.

That was the moment, on 8 September 1915, when a bomb landed just in front of the pub and exploded. Three men were killed in the blast and in the ensuing fire. One of them – fireman Green of the London Fire Brigade – succumbing to injuries sustained as he tried to rescue people from the nearby buildings.

The German Zeppelins L13, L10 and L11 en route to a bombing raid on London in 1915, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 58452

The German Zeppelins L13, L10 and L11 en route to a bombing raid on London in 1915, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 58452

London’s first major air raid

High above the city, German Navy Zeppelin L13, piloted by Kapitänleutnant Helmut Mathy, rose out of the range of anti-aircraft guns and moved off to the south-east in the direction of the coast.

London was experiencing its first major air raid of the First World War. By the end of the night 26 people would be dead and the concept of the Zeppelin Menace would be at the forefront of Londoners’ minds.

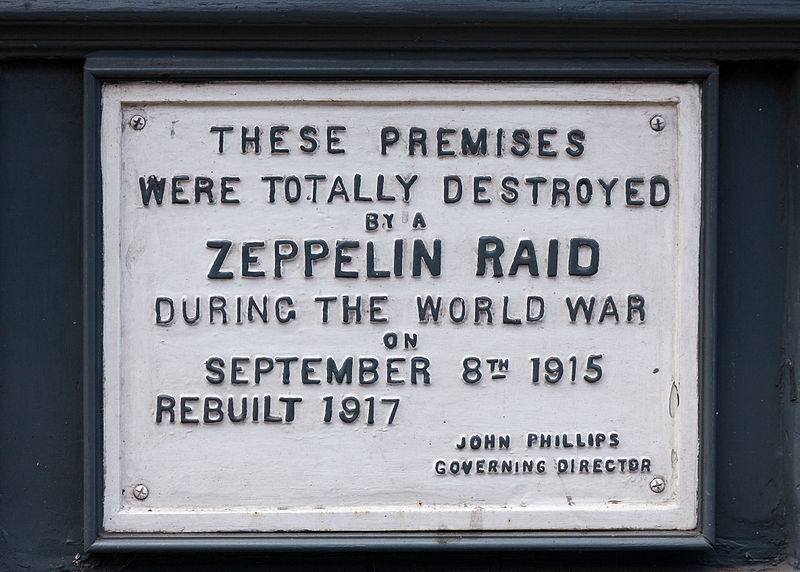

There are few reminders in London today of the Zeppelin raids of World War I, though one plaque near Farringdon Station records that the building on which it is fixed was totally destroyed by a bomb in 1915.

Plaque commemorating the raid, Farringdon Road

Plaque commemorating the raid, Farringdon Road

Nearby, Bartholomew Close in Holborn was one of the places worst hit, taking the brunt of a 300kg bomb that wrecked the houses there.

High above, Mathy witnessed the impact and wrote in his report: ‘The explosive effect of the 300kg bomb must be very great, since a whole row of lights vanished in one stroke.’

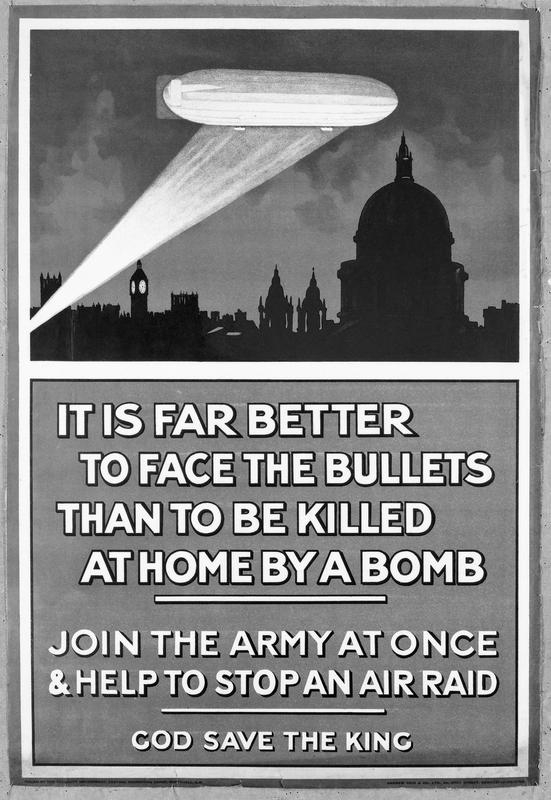

A British wartime poster which encouraged men to enlist in the face of the ‘Zeppelin menace’, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 80366

A British wartime poster which encouraged men to enlist in the face of the ‘Zeppelin menace’, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 80366

No parachutes

Watching alongside were the 17 other members of the Zeppelin’s crew, wrapped up against the -30°C cold in thick woolen underwear, their standard naval uniforms, leather overalls, fur overcoats, scarves, helmets and goggles.

Theirs was a particularly dangerous job. If anti-aircraft fire or machine gun bullets hit the airship, it could be swamped by fire in minutes. And, while parachutes were available for the crews, they were not always carried on board.

Two police officers stand by a crater caused by bombs dropped from German Zeppelin L15 on Chambers Street, Bermondsey, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, HO 13

Two police officers stand by a crater caused by bombs dropped from German Zeppelin L15 on Chambers Street, Bermondsey, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, HO 13

The thinking was that they would be of limited use over the sea and that if the Zeppelin was set on fire there would be no time to deploy them. Many crews believed they just added weight and, with every kilogram vital to their rate of climb and maneuverability, they were inclined to leave them behind.

A similar principle applied to defensive machine guns. While the airships were equipped with several of these, they were often dispensed with – the crews believing that being able to climb away from trouble was a better defence than trying to fight off a pursuing fighter plane.

Height was not always enough to ensure safety, however. On 31 March 1916, L15, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Joachim Breithaupt, was hit by anti aircraft fire from the Purfleet ranges – today the RSPB’s Rainham Marshes nature reserve. With four of its gas cells destroyed, the Zeppelin gradually lost height before crashing into the sea near Margate. All but one of the crew survived.

‘St George and the Dragon: Zeppelin L15 in the Thames’, by Donald Maxwell, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Art.IWM ART 888

‘St George and the Dragon: Zeppelin L15 in the Thames’, by Donald Maxwell, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Art.IWM ART 888

The tide turns

Others were less fortunate. On 3 September 1916 SL11 was shot down and crashed at Cuffley, Hertfordshire. The RFC pilot responsible for its destruction, lieutenant William Leefe Robinson, was awarded the VC.

A few weeks later, on 24 September, L33 was hit by anti aircraft fire over the East End of London and came down largely intact at Little Wigborough in Essex – the crew being taken prisoner.

Starboard amidships propeller boss fairing from wreckage of Zeppelin L33, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, EPH 2732

Starboard amidships propeller boss fairing from wreckage of Zeppelin L33, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, EPH 2732

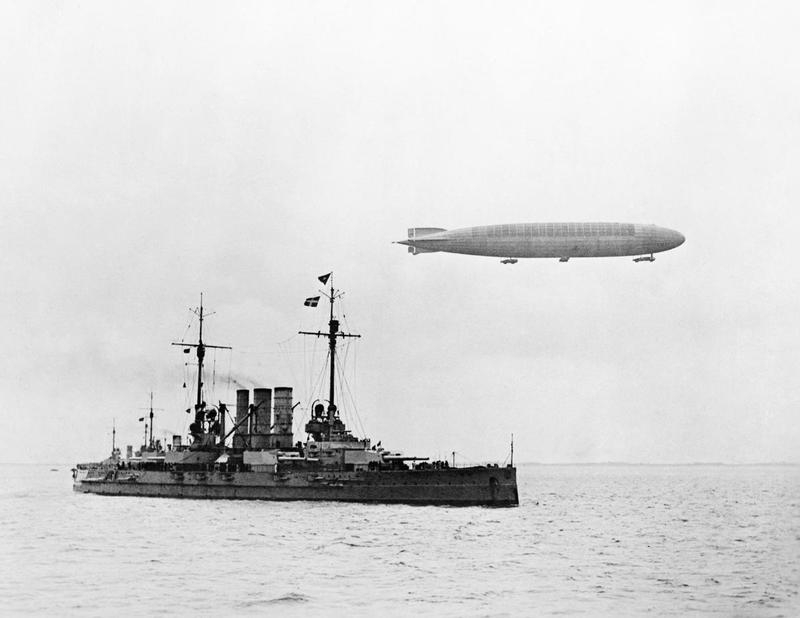

Then, on the night of 1-2 October, Mathy – whose bombs had caused havoc in central London the previous year – commanded one of seven airships to mount a raid on London and the Midlands. Unable to press home his attack on the capital because of anti-aircraft fire, he instead dropped his bombs on Cheshunt in Hertfordshire.

Nearby the Zeppelin was intercepted by an RFC fighter plane piloted by Second Lieutenant Wulstan Tempest.

‘I dived straight at her, firing a burst straight into her as I came,’ Tempest wrote afterwards. ‘As I was firing, I noticed her begin to go red inside like an enormous Chinese lantern and then a flame shot out of the front part of her and I realised she was on fire.

‘She then shot up about 200 feet, paused, and then came roaring straight down on to me before I had time to get out of the way. I put my machine into a spin and just managed to corkscrew out of the way as she shot past me, roaring like a furnace.’

L31 crashed into a field near Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, killing its entire crew.

The German naval airship L31 flying over the dreadnought Ostfriesland, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 58459

The German naval airship L31 flying over the dreadnought Ostfriesland, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 58459

Its wreck became an instant tourist site as Michael MacDonagh, a journalist on The Times, recorded the following day.

‘The train I caught was packed,’ he wrote. ‘My compartment had its 20 seats occupied and 10 more passengers found standing room in it. The weather too was abominable. Rain fell persistently. We had to walk the two miles to the place where the Zeppelin fell, and over the miry roads and sodden fields hung a thick, clammy mist. It was a joyful crowd all the same – very expressive of the racier spirit of London.’

For all the anxiety and terror they had brought with them, the tide was turning for the Zeppelins, but Londoners were soon to encounter another wave of attacks from the air. This time delivered by long-range Gotha bombers.

Gotha G.II heavy bomber of the England Squadron (Kagohl 3 or “England Geschwader”), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 73547

Gotha G.II heavy bomber of the England Squadron (Kagohl 3 or “England Geschwader”), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM, Q 73547

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author