On 20 April 1918 soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force engaged in their first significant military encounter of World War I at Seicheprey, near the St. Mihiel salient in north-east France. Troops of the 26th ‘Yankee’ Division were taken by surprise in an overnight raid by German stormtroops. As Patrick Gregory explains, the common assessment of the AEF troops’ performance at Seicheprey has been a mixed one.

The 26th Division was one of the first American Expeditionary Force divisions to arrive in France in 1917. One of the original ‘Big Four’ divisions – alongside the 1st, 2nd and the 42nd – the ‘Yankees’ were in fact the first completely-assembled AEF division in Europe, the last of its units having arrived by early November.

A National Guard force drawn from the New England states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Connecticut, the 26th was regarded as a competent and well-organised division, yet it was still some way off being considered ready for frontline action.

Build-up

Once he had gathered his forces, divisional commander General Clarence Edwards went on an observation tour with British forces for a month to study methods and tactics, while his men underwent training with French instructors over the winter of 1917-18. It was a slow build-up, but if the division was still shy of proper combat experience that was soon going to change.

On 1 February, divisional artillery units were moved into position in an area along the Chemin des Dames line north of Soissons in the Aisne, seeing some sporadic action under the French Sixth Army. Then, two months later, it was ordered into line near the St. Mihiel salient in the Ansauville sector, some 100 miles to the south-east. There, they were to relieve troops of the AEF’s 1st Division – a change of plan given the impact of the first of Ludendorff’s spring offensives on 21 March.

The salient, or ‘hernia’ as the French liked to refer to it, was a triangular bulge into French lines which had remained largely static for four years after a German flanking manoeuvre around Verdun halted in 1914. Their forces had since dug in and fortified the area sufficiently for it to become a ‘quiet’ sector. The tip of the salient was marked by St Mihiel itself while to its east – and nestling against south-east part of the salient – lay the town of Seicheprey.

US forays

During its own three-month tenure in the area beginning in January 1918, the 1st Division under General Robert Lee Bullard had begun to probe the German lines, determined not to allow the area to become a backwater. Impressing the message on his men that there were ‘no orders which require us to wait for the enemy to fire on us before we fire on him’, Bullard ensured some forays were mounted into enemy territory. Now, a few weeks later, and with a new division in place, German forces were ready to repay the compliment.

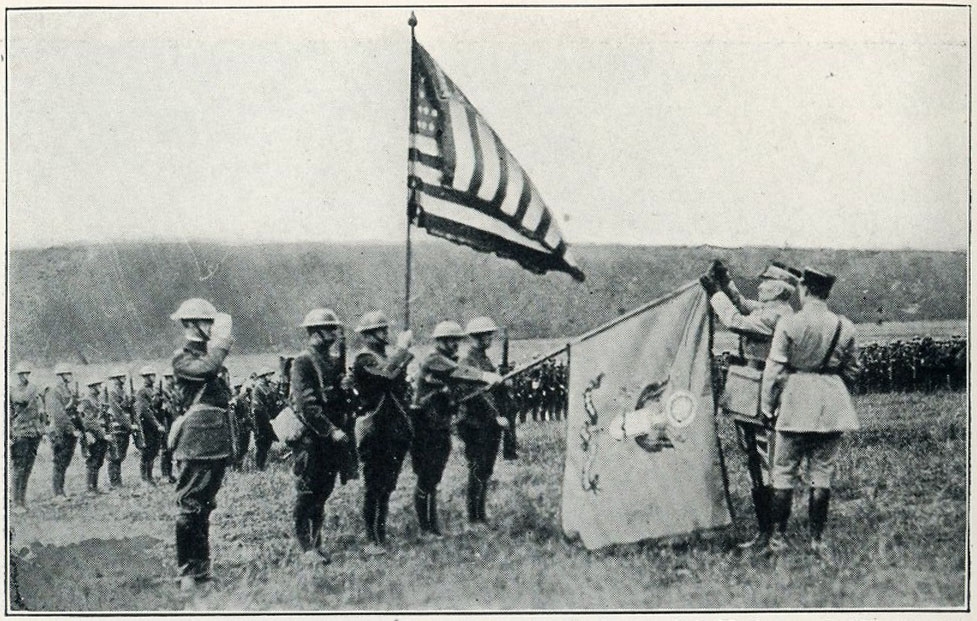

Decoration of regimental colours, 104th Regiment, US 26th Division, at Boucq by General Fenélon Passaga, 32nd French Army Corps – the first American regiment cited for bravery under fire (Image: Wikipedia/public domain)

Two initial raids were repulsed on 10 and 12 April by the Americans’ 104th Regiment. But then, after a fierce opening artillery bombardment in the early hours of Saturday 20 April, around 600 troops of a German Sturmbataillon, aided by troops from three other regiments, made their move. Over 3,000 men poured over the lines, headed for Seicheprey and the Remières woods to the east of the town. Telephone wires were cut, the American lines penetrated east and west of Seicheprey, the woods reported lost. All was confusion. The French corps commander in the sector, Major General Fénelon Passaga, arrived to try to take control of the situation from the 26th’s brigade commander Brigadier General Peter Traub.

Fightback

Yet in the town itself, a fightback had begun. Mustering together an ad hoc group of orderlies – cooks, bakers, clerks – and a detachment of 1st Division soldiers left behind in Seicheprey on a work detail, Major George Rau first held on, and then succeeded in driving the invaders out. Furthermore, the Remières woods were not all lost as had been reported. Fighting continued with soldiers of the 102nd and 101st Infantry holding the line.

But at that point the Germans took the decision to withdraw, claiming victory. They took with them 136 prisoners, having inflicted casualties of 80 dead and over 400 wounded. Two of the 26th’s infantry companies and a machine gun company were reduced by up to 50 per cent. For their part, the attackers left behind some 150 dead, part of total (admitted in a later official report) of nearly 600 casualties.

Lauded

So should Seicheprey be regarded as a success or a setback? Certainly at the time, the action was lauded at home: a time which coincided with the third Liberty Loan, then newly underway. Yet there was no escaping the fact that there had been mass confusion among the ranks of the Yankees when the German attack had hit home in the early hours of 20 April: a lack of communication and coordination hampering the troops’ response. The Americans had also lost a disproportionate number of prisoners taken by the enemy.

But that said, and equally true, the 26th ‘s troops had performed well when it had come to actual combat. They had gained some much-needed experience. Seicheprey represented a rite of passage for the men, a starting point. Yet there would be sterner tests to come.

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18’ (The History Press) American on the Western Front @AmericanOnTheWF.

Images: Wikimedia – Flickr Commons, no known copyright restrictions (Seicheprey aerial view); Wikipedia – public domain (26th Division)