After four days of intense fighting in the Meuse-Argonne, beginning on 26 September 1918, American Expeditionary Force commander General John Pershing called a temporary halt to most – though not all – offensive operations along the front. It had been hard going in the difficult uphill terrain and he wanted time to regroup his forces: withdrawing some divisions and introducing other, more experienced units. Patrick Gregory reports:

He had always known it would be difficult for his men but Pershing was nonetheless dismayed at the lack of progress made by some of forces in the four days’ fighting to date. It was time to think again. Some operations would continue in the Argonne forest, but the AEF leader would pause the main thrust of the offensive for now.

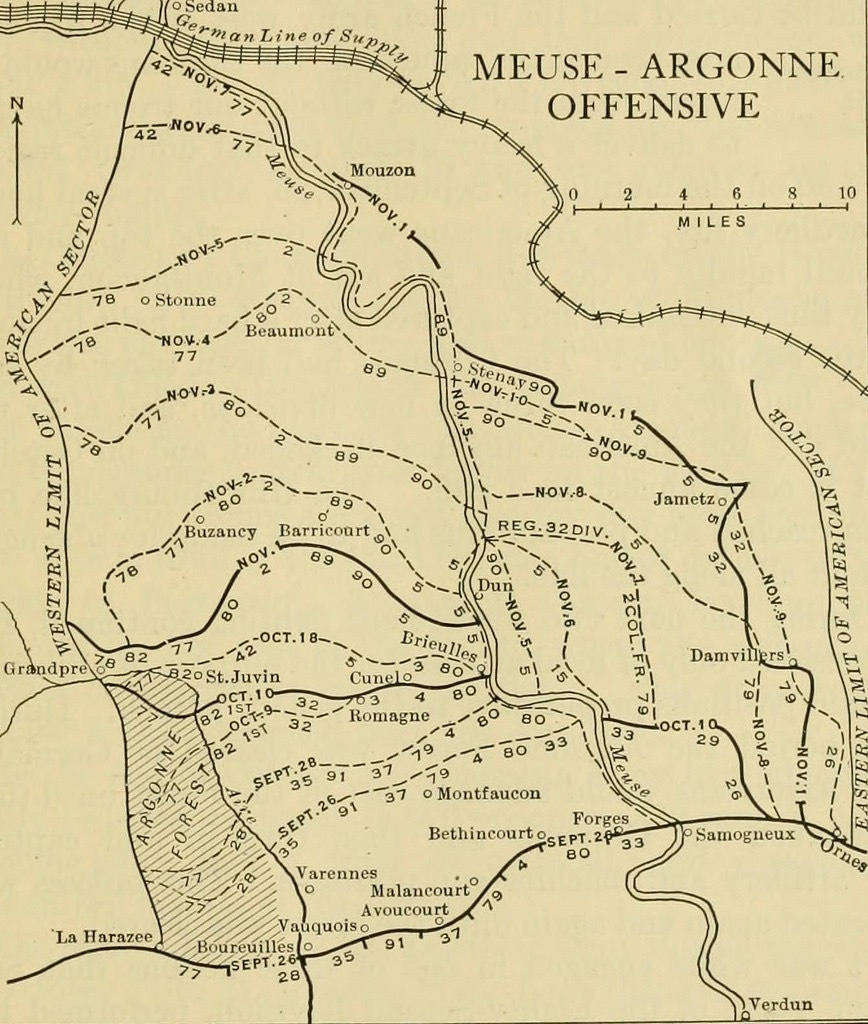

It had been a three-pronged attack by the American First Army. On the left, the Argonne forest attacked by the three divisions of Hunter Liggett’s I Corps. On the right-hand side, along the Meuse river, III Corps commanded by Maj Gen Robert Lee Bullard. And through the middle, the fresh but inexperienced divisions of George Cameron’s V Corps.

Meuse-Argonne map – showing dates & stages of battle (Image: Internet Book Archive/Library of Congress/Flickr/No known copyright restrictions)

Meuse-Argonne map – showing dates & stages of battle (Image: Internet Book Archive/Library of Congress/Flickr/No known copyright restrictions)

It was that latter central attack, in particular, which had stalled; and having been behind schedule capturing their first objective – the hill of Montfaucon – the 91st, 37th and 79th Divisions were making little headway towards their next objective, the ridge of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. Pershing decided to call time, withdrawing them and replacing them with two experienced divisions that had seen action during the summer in the Aisne-Marne campaign, the 3d and 32d.

To the left of the 3d and 32d – and on the right-hand side of Liggett’s I Corps – he also withdrew the 35th Division, the Kansas and Missouri National Guardsmen who had endured such a torrid time in the intervening days, suffering the highest casualty rate so far. It was to be replaced by the commander-in-chief’s go-to unit, the 1st Division. On the right side of the attack zone, meanwhile, the three divisions of III Corps remained the same.

Reviews of the campaign concluded what had become glaringly obvious in the four days of fighting: better liaison and organisation was needed. More liaison between corps and within corps to ensure proper coordination between units adjacent to one another; better strength in depth spread evenly throughout the lines of infantry; and closer liaison between advancing infantry and supporting artillery.

Relaunch

A new H-Hour and D-Day was set and at 0530 on 4 October all-out offensive was relaunched across the entire 12-mile front. Phase II of the Meuse-Argonne offensive was underway. It was a portion of the battle which would later come to be remembered in history books and in the cinema more for the tales of Charles Whittlesey’s ‘Lost Battalion’ of 308th Infantry (77th Division) in the Argonne forest and 82d Division’s Sergeant Alvin York and his exploits there in killing 20 members of a German machine gun battalion and taking some 130 more prisoner; but the offensive as a whole had a clear objective, to take the Heights of Romagne & Cunel in the middle of the attack zone and to try to break through the Germans’ heavily fortified line of the Kriemhilde Stellung.

The same three-pronged attack was to be employed, but this time with what commanders hoped would be a greater degree of common purpose. The three divisions on the right, closest to the Meuse advancing in a pincer movement through the village of Brieulles and the woods at the Bois des Ogons and Bois de Fay to close in on Romagne. On the opposite flank the 1st Division advancing on the right hand of the Argonne forest and along the Aire river to cross the Exermont ravine; again with the purpose of aiding the overall thrust towards the Romagne-spus-Montfaucon ridge. For their part down the middle, V Corps – albeit with the new divisions of 3d and 32d – still found the going slow, and was painstakingly inching its way up its zone.

Pershing would now press a fourth corps at his disposal – the French XVII Corps – into a more offensive position on the Heights of the Meuse, to engage more actively with enemy artillery units on the far bank of that river and relieve some of the pressure on those AEF units within firing range.

American commanders in the Meuse-Argonne: Hunter Liggett (left) and Robert Lee Bullard (Images: Library of Congress/No known restrictions)

It would take until 13 October to capture Romagne and Cunel: a boost to those forces involved when it happened, but little more than that for now. It remained only a staging post on a long and gruelling push north. The German army in the region was on the back foot, pulling out of some areas but still intact. An expanding American Expeditionary Force was spawning a Second Army, with Pershing ceding control of First Army to Hunter Liggett and appointing Bullard to lead the Second. Much fighting remained to be done.

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18’ (The History Press) American on the Western Front & on Twitter @AmericanOnTheWF.

Also by Patrick Gregory in Centenary News – report from Meuse-Argonne centennial commemorations at the American WW1 cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon.

Images:

US soldiers in trench – via Wikimedia Commons/US official photo/public domain: From Colliers New Encyclopaedia, 1921

Meuse-Argonne map – Internet Book Archive/Flickr/No known copyright restrictions/Contributing Library: The Library of Congress – From page 670 of ‘A history of the United States’ (1921), Authors: Lataé, John Holladay, 1869-1932

Generals Hunter Liggett, Robert Lee Bullard – Library of Congress/No known restrictions: From National Photo Company Collection Loc 2016821112 (Hunter Liggett), Bain Collection Loc 2005676891 (Bullard)