Publisher’s Description

“This is a magisterial new account of Europe’s tragic descent into a largely inadvertent war in the summer of 1914.

Thomas Otte reveals why a century-old system of Great Power politics collapsed so disastrously in the weeks from the ‘shot heard around the world’ on June 28th to Germany’s declaration of war on Russia on August 1st.

He shows definitively that the key to understanding how and why Europe descended into world war is to be found in the near-collective failure of statecraft by the rulers of Europe and not in abstract concepts such as the ‘balance of power’ or the ‘alliance system’.

In this unprecedented panorama of Europe on the brink, from the ministerial palaces of Berlin and Vienna to Belgrade, London, Paris and St Petersburg, Thomas Otte reveals the hawks and doves whose decision-making led to a war that would define a century and which still reverberates today”.

Centenary News Review

Reviewed by: Alan Paton

This is an outstanding book. Certainly, as measured by the number of bookmarks I made “I didn’t know that”, “that’s interesting”, “I must read that again”… it warrants that description.

It is a narrative of what happened and why, from the plotting of the Archduke’s assassination to Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on the 4 August and it divides that fraught period into helpful sub-divisions and managers very well the difficult task of describing so much going on in parallel without confusing or losing the reader. The author also has the knack of selecting just the right bit from the many telegrams, diaries and other primary sources he quotes.

It is a good read throughout. I personally found the account of how the Austro-Hungarians reacted, got Tisza, the Hungarian prime minister, to fall into line, and made their decisions, especially informative and convincing. There is neat balance of facts and interpretation.

There is also plenty to argue with. Jagow is given a much stronger role than I expected even to the extent of giving the Austro-Hungarians a “second blank cheque” seemingly without Bethmann’s approval or knowledge. Jagow and Stumm are credited with undermining the Kaiser’s “halt in Belgrade” proposal without reference to Bethmann when it was forwarded to Vienna but it seems to me most unlikely that Bethmann did not see and fully approve such an important communication going out over his signature. And, it was the point where Germany’s plans were beginning to unravel

The roles of two ambassadors, Paleologue the French ambassador in St Petersburg, and especially Tschirschky the German ambassador in Vienna, while not over played, are shown to be most emphatically negative, pushing in the direction of war.

A most striking feature is the rehabilitation of Grey, the British Foreign Secretary. The author blames Lloyd George for the picture of Grey as the man who failed to warn Germany in time that Britain would side with its Entente partners. He doesn’t mention Albertini’s scathing assessment of Grey’s role. He believes Grey made it clear in the first week of July in conversations with Lichnowsky, the German ambassador, that there could be European complications, and the problem was largely that Berlin did not believe Lichnowsky’s accurate reporting and analysis of the British position.

However, later on, he discusses a meeting on the 22 July between Grey and the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in which Grey talks about the possibility of a four Great Power war, i.e., Russia, Germany, France and Austria-Hungary. No Britain in this war! Also, though Grey could not be held responsible for what King George said to the Kaiser’s brother (Britain would try to remain neutral) or how the brother reported it to the Kaiser, or how his German naval colleague reported it to Berlin, Grey should have been more alive to the strength and persistence of the German belief that Britain would stay out of any war.

The author addresses head on the issue of who or what to blame for the outbreak of the war in a dedicated, and convincing, chapter at the end of his book. Without giving too much away I will say he doesn’t blame the “alliance system” or the “arms race” or “domestic factors” or “German imperialism”.

Even in an excellent book you can find something to gripe about. In the section dealing with the assassination the author says that Apis of the Serbian Black Hand secret society was the instigator and mastermind of the plot is “now widely accepted by scholars of the period”. Princip and his fellow assassins were only “useful idiots” recruited by one of Apis’ henchmen. A recently published and very well researched book by the journalist Tim Butcher, makes it very clear, even though the Black Hand supplied the weapons, Princip independently and for his own reasons decided to assassinate the Archduke. Another new book by Greg King and Sue Woolmans says there were two plots that were merged into one.

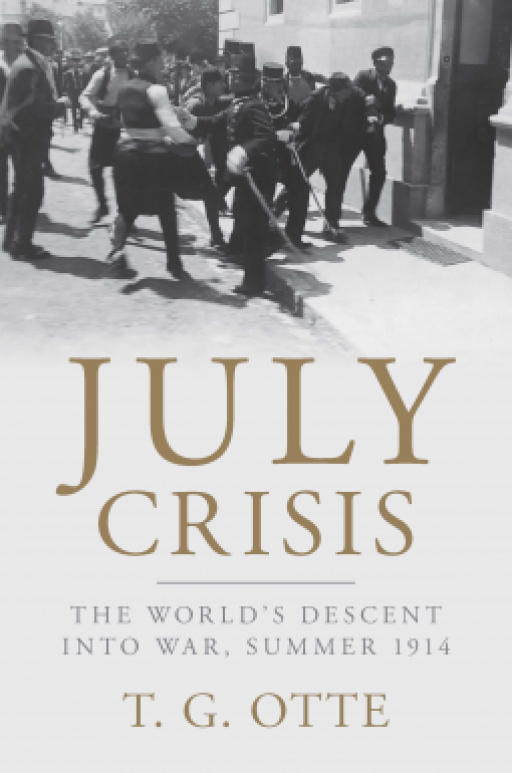

That photo on the cover of the hardback is not the arrest of Princip but the arrest of an innocent bystander, Ferdinand Behr, who tried to protect Princip from the wrath of the crowd”.

To find out more about the photo, which was presumed to be of Princip, you can read Alan Paton’s article on the subject here.

What do you think about this book or review? Please add a comment below.