Publisher’s Description:

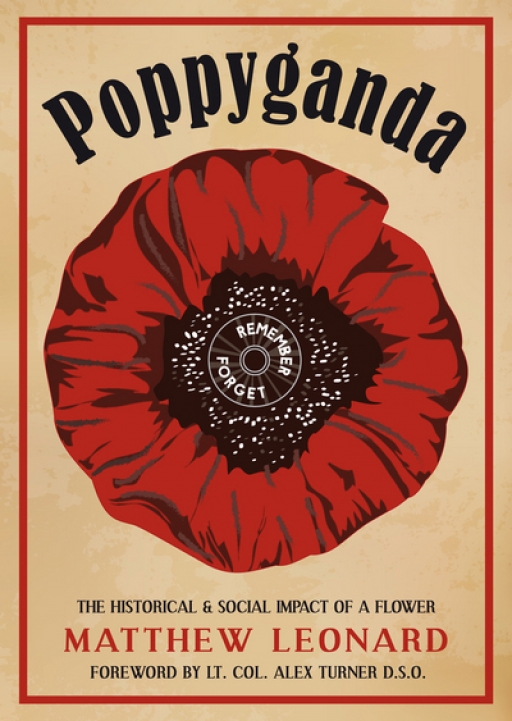

‘The poppy is the enduring symbol of the First World War, an icon that embodies a hundred years of attitudes towards the world’s first great conflict. Yet the flower’s association with warfare pre-dates 1914 and its legacy continues today. An intensely powerful object, it has been appropriated by many, employed to justify war and to highlight its futility.

This is the story of how the modern relationships between man and nature, war and politics, the media and technology are writing another chapter in the story of this most notorious of flowers. This small wonder reflects the way that the war profoundly changed understandings of conflict, life, death, injury and the representation of human beings and the world they live in during the twentieth century. Concisely written, and using powerful contemporary and modern imagery, this book will mirror the poppy itself; striking, multi-layered and thought provoking.’

Centenary News Review:

Review by: Eleanor Baggley, Centenary News Books Editor

The symbol of the poppy today, worn on lapels around the country every November, is truly embedded in our collective memory of the First World War. We see the poppy and automatically associate it with the mud-soaked battlefields of France and Belgium. In reality, the poppy’s history is far more complex than many of us know.

Matthew Leonard’s Poppyganda goes some way to examine this history. It is a slim volume, just over a hundred pages long, but the book itself is an object to behold, filled with excellent quality photographs and images arranged artistically around the text.

Poppyganda is a truly thought-provoking read. I’m personally guilty of assuming I know the history and symbolism of the poppy, but in reality I knew very little about how that little red flower became quite so powerful today and throughout history.

Leonard begins the book with a discussion of the battlefields themselves, setting the scene for his later chapters. This chapter is a bit of a whistle-stop tour, but it’s detailed and concise and Leonard draws on a range of sources, from literature to art.

Wild poppies near the ‘Sunken Road’ on the Somme, July 1st 2014 (Photo: Centenary News)

Wild poppies near the ‘Sunken Road’ on the Somme, July 1st 2014 (Photo: Centenary News)

Often linked with John McCrae’s poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, the poppy actually became a significant image thanks to the campaign of an American woman, Moina Belle Michael. Inspired by McCrae’s poem and keen to do more for the war effort, Michael called for the poppy to be worn in memory of the American soldiers killed in the war. In Europe Frenchwoman Anna Guerin also recognised the importance of a symbol of remembrance and arranged for silk poppies to be manufactured in France, with the proceeds going to the war widows. The British Legion soon adopted the flower and for the first poppy day in 1921, nine million silk flowers were ordered. The following year the poppies would be made in Britain by the war wounded.

Today the poppy has been thoroughly commercialised. It is impossible to walk through the streets of Ypres and not catch sight of the myriad tourist trinkets emblazoned with the symbol. Leonard argues that the poppy is now used as propaganda and a way of legitimising the version of events portrayed on the Western Front of today.

Leonard ends the book with a significant caveat: though he still believes that the poppy is now propaganda, he accepts that it is important to note that bringing the poppy into the public eye annually ensures that we will remember, albeit briefly, those who fell in the First World War and in conflicts since.

Although it’s clear that Poppyganda barely scratches the surface of the subject and that there are other authors who have delved deeper (for example Nicholas J. Saunders in ‘The Poppy’), this book is an excellent and intriguing introduction. It provides enough detail to satisfy the curious mind, but also to whet the appetites of those who wish to know even more. I certainly fall into the latter category.

What do you think about this book or review? Please add a comment below.