Mike Swain reports on a new exhibition being held at the University of Manchester’s John Rylands Library in England.

Four poignant letters written by students from the battlefields of the First World War to their history professor are being seen in public for the first time.

The letters were written to history professor Thomas Frederick Tout by students at Victoria University of Manchester.

They are being shown in a free exhibition called Aftermath at the University of Manchester’s John Rylands Library alongside six specially commissioned works by University of Salford visual arts students.

A piece by Suzanne Smith, a University of Slaford student

One of the letter writers, Herbert Eckersley, killed in action in 1917, was one of 300 Victoria University of Manchester students who lost their lives in the Great war, according to a 1918 speech by the then Vice-Chancellor Sir Henry Miers.

Eckersley was killed near Ypres in November 1917 and the last letter he wrote to Professor Tout just 15 days before he died expresses the hope that he will soon be back in Manchester and working on his thesis.

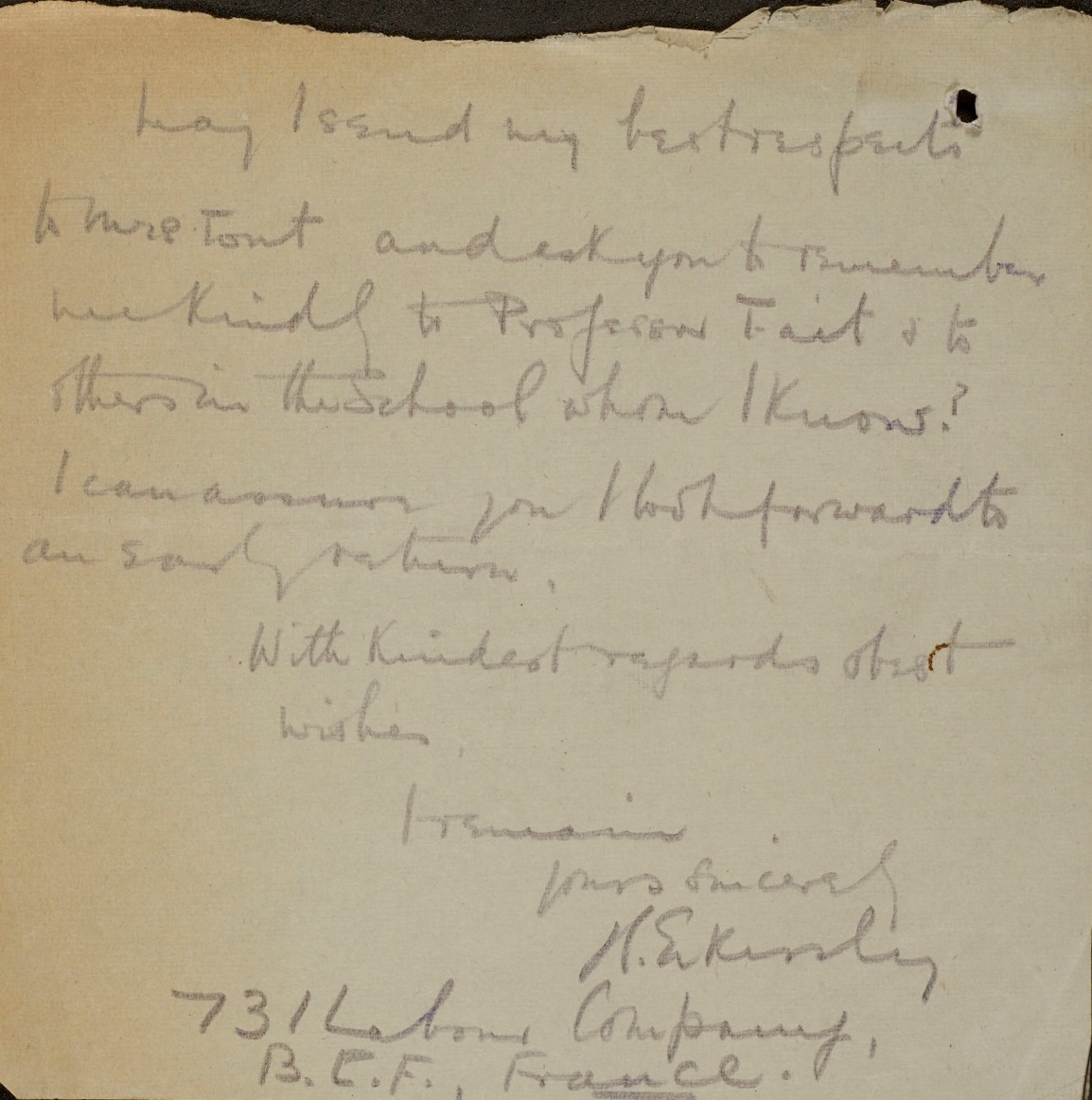

Herbert Eckersley’s letter

Herbert Eckersley’s letter

The other letter writers are conscientious objector J Stanley Carr, who survived the war, Thomas Seymour Hurrell, who survived but died in the flu epidemic in 1918.

It is not known what happened to the fourth letter writer SL Connor.

In One extract Connor writes of his friend Ben Westfield “missing believed killed.”

Connor writes: “On Monday April 23 he led his men “over the top.” Ten minutes later at 10pm he fell with a bullet through his lung and shrapnel wounds in his head and foot.

His servant Scholes remained with him.”

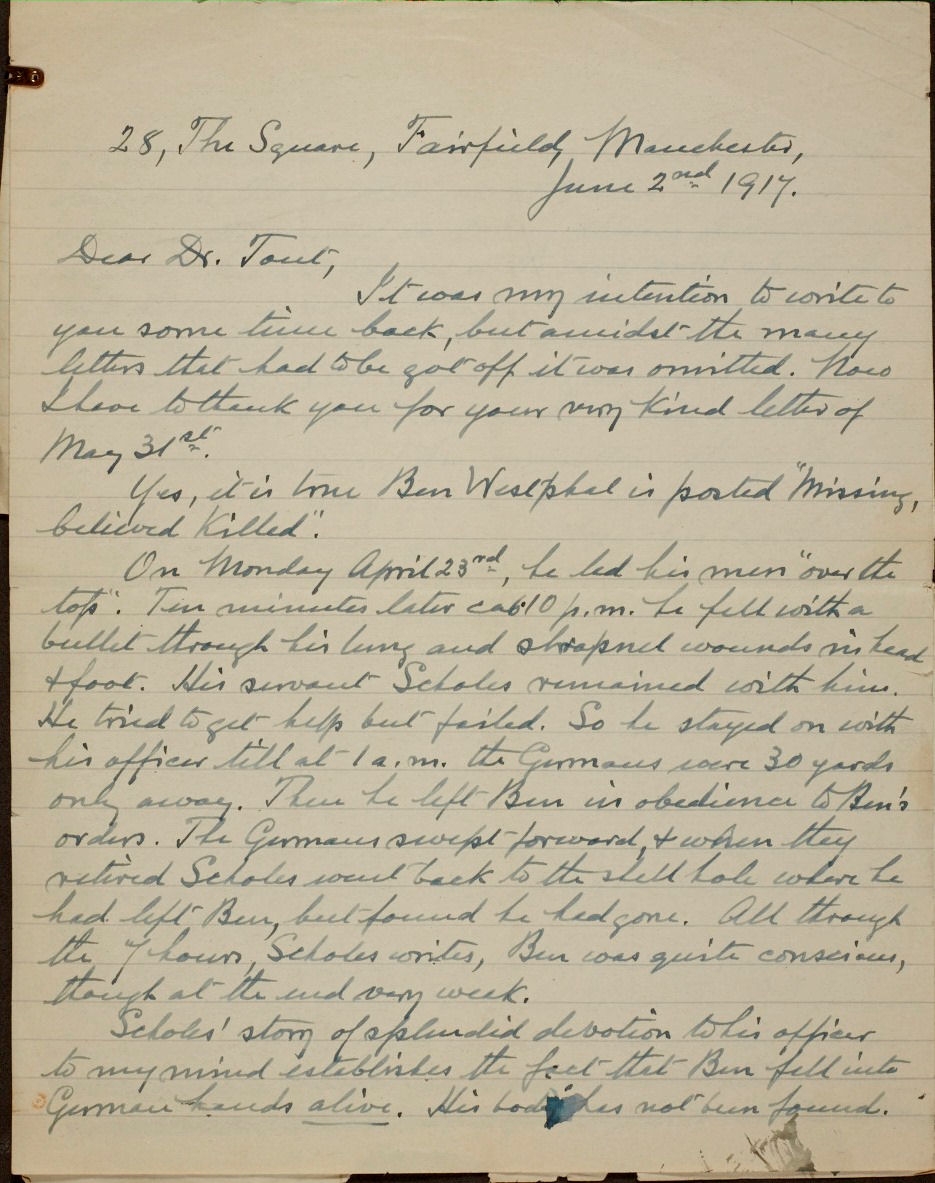

The letter by Connor

The letter by Connor

Connor says Scholes eventually left Ben, who was still alive. The Germans swept forward and when Scholes returned Ben was missing from the shell hole.

“For nearly twelve years our home has been his home. Ben was a modern man but his faith was very deep and real.

“His poor parents do not understand. They will understand one day.”

Eckersley’s enthusiastic letter dated 29 October 1917 begins: “Everyday seems more interesting and exciting than the previous one and as I am well in “the push” I hope to initially thrill you. I would like to.”

Clearing shell holes he records a lucky escape: “I was knocked over by a big piece of shell which would ordinarily have killed me.

“I had fallen my men out for a rest when the thing burst in the air, high explosive.

“A piece as big as my fist caught me in the side as I lay on the ground. Somehow or other it caught me round side on and beyond scorching my tunic, breaking the skin a little and heavily bruising me, nothing happened.

“The Canadian who dressed me told me it was better to be born lucky than rich in the army and in two days I was back on duty..”

He adds later: “The general feeling out here is one of cheerfulness and everybody seems very sanguine about an early finish. I hope so and certainly we seem to have the upper hand.

“So, I too am very cheerful that all pervading mud and filth you may see me back next October doing a thesis.”

As well as the 300 killed 20 Victoria students were missing, 20 taken prisoner, two repatriated and one escaped from prison. The Victoria University merged with the Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) in 2004 to become the University of Manchester.

Commenting on the commissioned art works , Jill Randall, University of Salford Senior Lecturer said: “Archive research is creative thinking, a creative act and has proved a source of huge inspiration for our B.A Visual Arts students.

“It has alternatively amused and moved them to tears, and has produced very rich and varied responses, ranging from printed books to sculpture to textile pieces, each a personal response to a letter or set of letters, creating a new highway to the past, a new way of telling the story, reinvesting forgotten people and histories and making them relevant to the 21st Century.”

The exhibition also includes watercolours from the front by soldier Walter Phythian and a poem by popular poet Katharine Tynan. There are also photos from Grangethorpe hospital in Rusholme, Manchester.

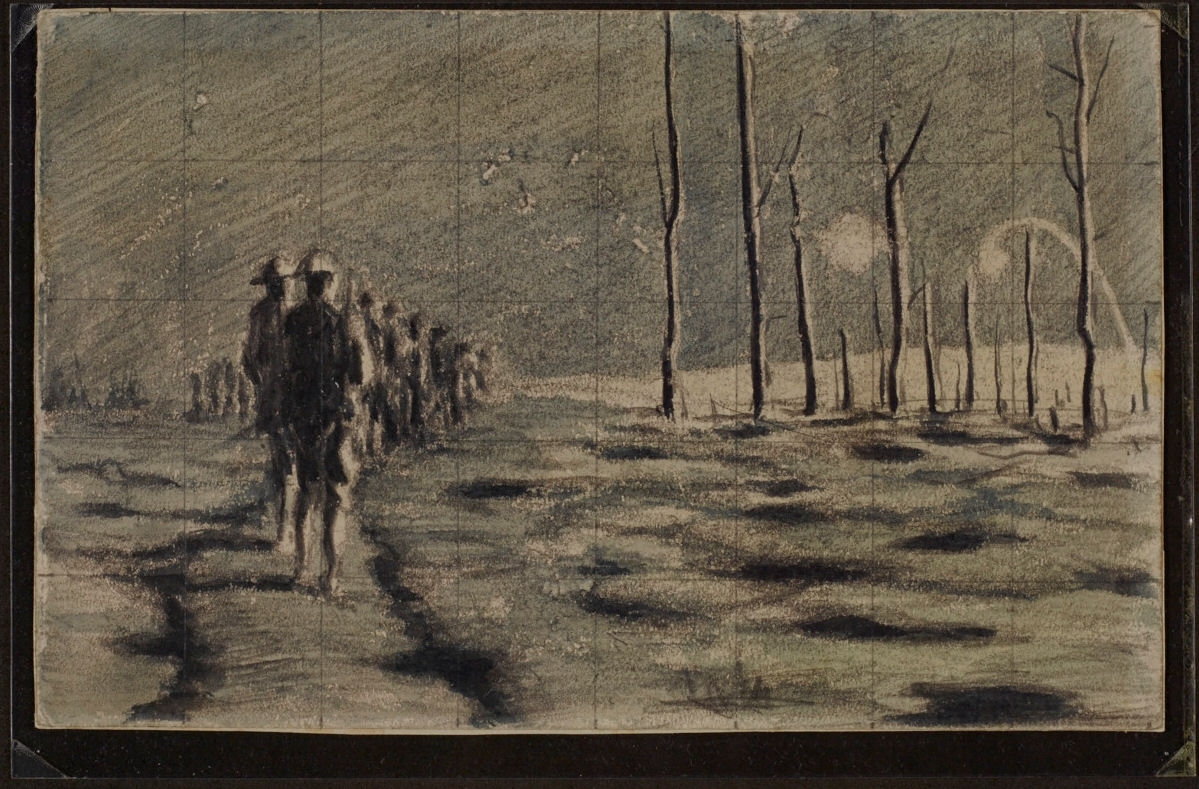

One of Walter Pythian’s watercolours

One of Walter Pythian’s watercolours

John Rylands Library co-curator Jacqui Fortnum, said: “It’s remarkable how in the face of such appalling experiences during war, so many people have found a way to be compassionate and creative.

“Aftermath brings together examples of protest, reflection, memorial and invention. These represent the stories of people across the world , throughout history and from every walk of life whose lives have been forever changed by conflict.”

Aftermath will run until June 29 2014.

Grangethorpe Hospital

Grangethorpe Hospital

From material supplied by University of Manchester

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author