Dr. Jillian Davidson writes about the impact of the First World War on the Jews and expresses her opinions on the work of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Although the catastrophic origins of the American Joint Jewish Distribution (JDC) only merit commemoration, its phenomenal philanthropic efforts and achievements deserve to be celebrated.

The New York Historical Society has fittingly taken a celebratory tone in its new exhibition “I live. Send Help.” 100 Years of the American Joint Distribution Committee. This exhibition about funding is in itself funded by true disciples of the Joint, Marcia and Alan Leifer, who recognize the importance of contributing money towards a worthy cause. It is on display from June 13 to September 21, 2014.

The JDC was founded in NYC in 1914 as a direct response to the plight of destitute Jews in Palestine and Eastern Europe. From its outset, World War One devastated the lives of Jews and disrupted their traditional revenues of support.

The Jews of Palestine were mostly citizens of states at war with Turkey and Turkish persecution of Jews was draconian. Jews fled from Palestine to Egypt, where they barely had the wherewithal to survive. The Ottoman Empire blockaded Palestinian ports during the War. Remaining Jews in Palestine lost access to their sources of income and faced arrests and confiscations.

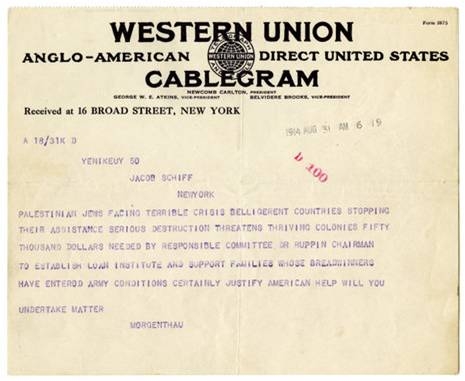

As early as August 31, 1914, American Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau Sr., sent a cablegram to Jacob H. Schiff, appealing for aid to help the Jews in Palestine. “Palestinian Jews facing terrible crisis. Belligerent countries stopping their assistance. Serious destruction threatens colonies.”

Cablegram from Ambassador Henry Morgenthau; courtesy of the American Jewish Committee Archives

Cablegram from Ambassador Henry Morgenthau; courtesy of the American Jewish Committee Archives

Jacob H. Schiff, a German-born American banker, was a co-founder with Louis B. Marshall, of the American Jewish Committee (AJC). This committee was established in 1906 in the wake of Russian pogroms to “prevent infringement ofthe civil and religious rights of Jews and to alleviate the consequences of persecution.”

Schiff replied immediately to Morgenthau’s cable: “Have called prompt meeting of American Jewish Committee which will no doubt undertake this. Should this not be possible I shall do it personally.” Within two days, they raised the $50,000.

The AJC helped to create the JDC. Representatives of 40 US Jewish organizations met in NY in November 1914 to discuss the coordination of relief for war-devastated Jewish populations. On November 27, 1914, they founded the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee for the Relief of Jewish War Sufferers (the JDC or “Joint.”) It was called the Joint because assimilated German Jews, orthodox Jews and socialist Jews united to save Jewish victims of the war.

Professor Yehuda Bauer has traced the history of the Joint. It began with American German Jews, who were not ethnically Jewish, but who had from the nineteenth century a very strong global sense of obligation to their co-religionists. In 1914, they needed to involve Russian immigrants who had already developed organizations.

So American German Jews merged with two types of Russian Jews: the orthodox and the socialists. The socialists themselves were divided between Zionists and non-Zionist socialists. The orthodox and the socialists did not talk to each other and the Zionist socialists and the non-Zionist socialists did not talk to each other. Each group, however, would talk to the German Reform or Liberal Jews. “It was called the Joint,” Bauer says, “because it was a token collaboration” between these very diverse ideological, geographic and social groups of Jews.

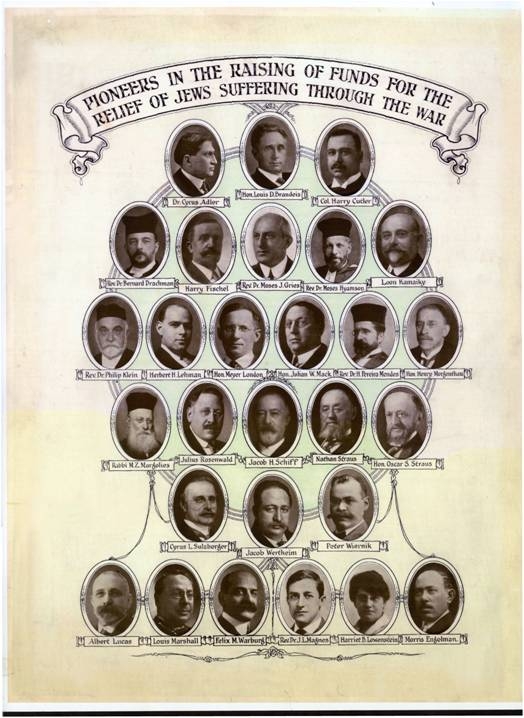

Pioneers in Raising Funds for the Relief of Jews Suffering through the War, 1917, courtesy of Yeshiva University Archives, Central Relief Committee Collection

Pioneers in Raising Funds for the Relief of Jews Suffering through the War, 1917, courtesy of Yeshiva University Archives, Central Relief Committee Collection

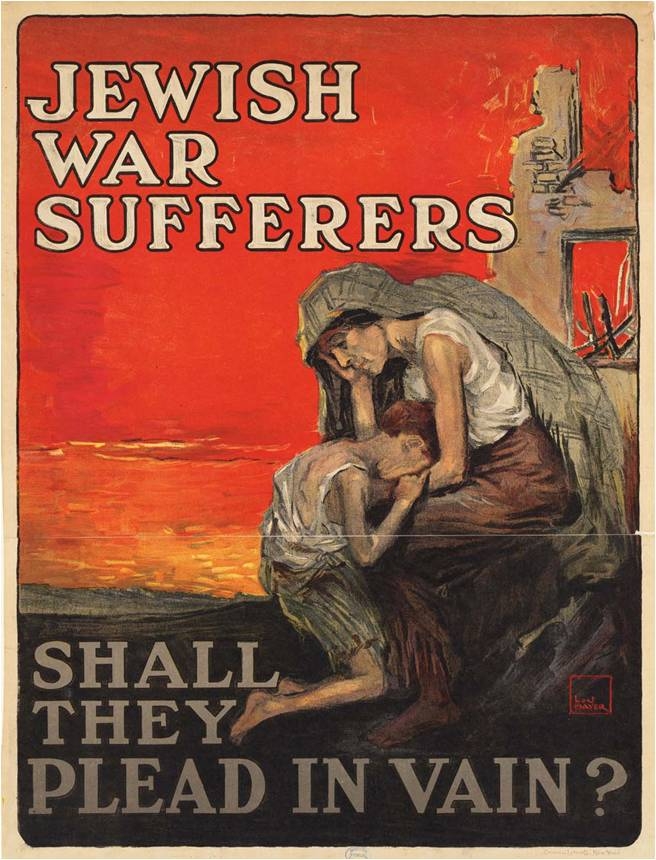

The exhibition charts a century of charity, which began in World War One. It shows the pioneers who raised the wartime funds and the means which they used, ranging from a household dime bank to Louis Mayer’s lithograph appealing for contributions: “Jewish War Sufferers: shall they plead in vain?” (c. 1917) and to a list of remittances sent to Jerusalem from the U.S. on September 13, 1918, ranging from $2.50 to $20. Altogether, throughout the war, the JDC helped to raise over $16 million in funds, food and medicine for Jews in need.

Jewish War Sufferers, Shall They Plead in Vain? 1918 Courtesy of Yeshiva University Museum

Jewish War Sufferers, Shall They Plead in Vain? 1918 Courtesy of Yeshiva University Museum

Demands for Jewish relief did not diminish with the conclusion of war. Albert Lucas, Secretary of the JDC, wrote to Felix M. Warburg, its head, of the need for a post-war relief policy to care for war orphans. “Upon the Jews of the countries where the actual horrors and sufferings of the war have not been felt should fall the task of providing the funds by which these children can be raised to self-respecting, self-sustaining manhood and womanhood. Doubtless American Jewry will do its full share in this, as it has shown its ability and willingness to bear the largest part of the burden of helping Jewry in the devastated lands to keep alive, while death in so many forms has lurked over countless thousands.”

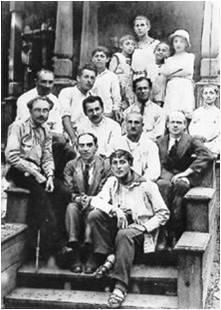

The JDC responded by setting up relief stations, refugee shelters, soup kitchens and milk distributions. They sent relief representatives, doctors and social workers. The exhibition includes a photo of artist Marc Chagall with other teachers at a JDC-funded school for war orphans in Malakhovka, Russia c. 1921-2. The JDC also brought war orphans to the US.

Marc Chagall with other teachers and children at a JDC-funded school and camp for war orphans in Malakhovka, Russia. C. 1921-1922, courtesy of JDC, NY

Marc Chagall with other teachers and children at a JDC-funded school and camp for war orphans in Malakhovka, Russia. C. 1921-1922, courtesy of JDC, NY

In 1928, John D. Rockefeller Jr. wrote a letter to James Rosenberg, the Chairman of the American Jewish Joint Agricultural Corporation (Agro-Joint), which resettled over 70,000 Russian Jews in agricultural colonies. Rockefeller praised the Joint’s work: “In a matter of this kind, there ought to be no barriers of race or creed. Therefore, although my participation has not been solicited, I hope you will allow me to enclose my check for $100,000.”

The rest of the exhibition documents the JDC’s contribution to tikkun olam, to “repairing the world”, beyond World War One. “This centennial celebration highlights the organization’s profound impact on the lives of Jews and non-Jews alike in over 90 countries around the globe from those early years in 1914 to the JDC’s most recent relief activities rebuilding Jewish communities in the former Soviet Union and aiding the victims of the November 2013 typhoon in the Philippines.”

As I walked through the exhibit in awe of the spirit and substance of the Joint’s work, I also listened to the comments of the constant flow of other museum visitors. One visitor, however, glancing at the glass-enclosed case which told of the JDC’s efforts at the time of the Holocaust, uttered a cry of censure: “I’ve seen enough of this. Why do they constantly show us the Holocaust? What is the point of this exhibition?” To her side, however, a fellow visitor, who was tracking the exhibit chronologically, responded out loud repeatedly to the letter of Morgenthau to Schiff and the surrounding World War One material: “I did not know about WWI. I knew about WWII but I didn’t know about WWI.” It was almost as if this visitor was answering the other’s question. The point of the exhibition is surely to show the Joint’s incredible record of relief and to show that its origins lay not in World War Two, but in World War One.

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author