CN writer, Jillian Davidson, visited the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and gives an account of its centenary exhibition, ‘World War I: War of Images, Images of War’, which examines the art and visual culture of the First World War.

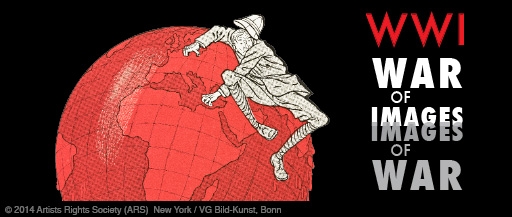

A Global Panorama at the Getty Center; “World War I: War of Images, Images of War”

To commemorate the Centenary, now on view at The Getty Center is America’s first major transnational and transitional exhibition on World War One. By nature of its more comprehensive geographic and temporal scope, “World War I: War of Images, Images of War” distinguishes itself from other WWI exhibitions currently on display across the United States.

Take, as fine examples, “Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind,” now showing at the New York Public Library in Manhattan, or “Over There! Posters from World War One,” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, or “Postcards from the Trenches: German and Americans Visualize the Great War,” at The Printing Museum in Houston, or even “Over By Christmas,” at the National World War I Museum in Kansas City. This exhibition in Los Angeles, which runs from November 18, 2014 to April 19, 2015, moves away from American introspection in favor of a more universal and long-term retrospective of the war.

Visitors are immediately struck by this impression. Upon entering, there is a mural timeline indicating the key dates of World War I, with America’s contribution to the war featuring only three-quarters of the way along the line. While there is also a column, which displays front pages of American newspapers announcing the outbreak of war, the headlines further emphasize its European magnitude. According to the Bismarck Daily Tribune of North Dakota, on Wednesday August 5th 1914, “England Declares War On Germany; All Europe Is Now Plunged Deeply Into Worst Conflict of History.”

The propaganda of war

After this introduction, the exhibition divides thematically and chronologically into three main sections. The focus in its first room is on the early propaganda war which combatant nations fought. Maps and cartographic caricatures produced by the artists of Europe’s warring nations feature in much of this propaganda. There is the German, Walter Trier’s “Karte Von Europa im Jahre 1914,” which depicted countries in images of inanimate objects, animals and people. Thus, Belgium, overrun by German troops, is pictured as a pistol in the hand of Germany. Serbia, a major exporter of pork at the time, is depicted as a pig and England assumes the persona of a dour Scotsman with Ireland in the form of his gnarling bulldog.

The image of the globe is a spherical symbol that dominates this room. German artist, August Gaul, depicted Britain as a sea lion balancing a globe on his nose, in reference to her precarious naval predominance. French illustrator, Henri Zislin, compared Napoleon’s “benevolent” bid for world dominion with Wilhelm’s crushing assault. Whereas Napoleon steps lightly on a sun-drenched globe, Kaiser Wilhelm, stomps his heavy boots upon a colorless globe subsequently reduced to a skull’s head. Beneath is the challenging caption “Such will they ever remain in the memory of man.”

The German-Jewish cartoonist, Thomas Theodore Heine, in Simplicissimus 1915, drew a scrawny Englishman in a colonial pith helmet skidding off a globe drained and dripping with red blood. Open to interpretation, this image, which is also the banner image for the exhibition, simultaneously suggests that in British strength lay British weakness, that Britain’s bid for world power caused the world’s bloodbath, and that Britain’s inability to rule condemned it to lose control and potentially the war. The caption underneath reads, “Curses! Blood is more slippery than water!”

The experience of war

The exhibition reflects upon the shift from War of Images to Images of War by turning away from the mediated war towards an unanticipated war; away from competing national claims of cultural superiority to personal responses of individual soldiers; from state satire to somber or sometimes apocalyptic art; from illusions to reality; from hopes to disillusionment; from ideals to experience; from political manipulations of war to the actual human horrors of modern trench warfare. Visitors appreciate this stark change as soon they enter the second main room of the exhibition.

In this second room, visitors encounter the apocalyptic sketches of the German Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, drawn in miniature on the backs of cigarette packages, as the artist suffered a nervous breakdown after two months of military service. Here too are the etchings of Belgian artist, Henry de Groux: a long row of black and grey slain bodies in “Massacre,” 1914-16, or his even busier and more alien “Masked Soldiers” wearing gas masks. There are also the horrifying black and white woodcuts of another Belgian artist, Frans Masereel: of “Soldiers on Barbed Wire,” “Dead Soldiers” and “Dismembered Soldiers.” There is the wasteland of “The Yser near Nieuwpoort” 1914 by French artist Lucien Henri Grandgérard, depicting the great human cost accrued from the battle, which halted further German advance. There is the German, Max Unold’s “Street Battle in Louvain,” which shows the city of Louvain under attack and in flames.

The shift in the second room from the War of Images to Images of War is also encapsulated by two radically different quotes on the wall of each room. The quote in the first room is from the editors of the Italian periodical, Lacerba, on August 15 1914: “But as this is a war not only of guns and ships, but also of culture and civilization, we are making a point of taking sides immediately and of following the events with our hearts and souls…. This is perhaps the most decisive hour in European history since the end of the Roman Empire.” The second quote is from Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire: The story of a Squad in December, 1916: “War is frightful and unnatural weariness, water up to the belly, mud and dung and infamous filth. It is befouled faces and tattered flesh… It is that, that endless monotony of misery, broken by poignant tragedies.”

The aftermath of war

At the threshold to the third room, loom two more maps – a small one of Europe in 1914 and the other, much larger, of Europe in 1919. Apart from illustrating the obvious geo-political changes imposed upon the face of Europe—the collapse of Empires, the redrawing of borders—the second map also enumerates the death toll suffered by each former combatant country. In order to approach “The Aftermath” of war, one must, at the very least, acknowledge these statistics.

Even though this third room begins with Armistice parades in London and Paris, it is implicit from the outset that the pain of loss and destruction tempered such celebrations. As the exhibition’s subtext narrates:

“Celebrations erupted in all the Allied nations across the globe, but especially in Europe, following the announcement of the armistice on November 11, 1918…. At the same time, there was immeasurable damage to the European landscape. The ancient city of Ypres in Belgium, reduced to rubble, became the symbol for such devastation… As much as it was a time of celebration, it was also a time of sadness and mourning.”

Pitted against images of victory celebrations in this room, visitors confront images of horror and mourning by artists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz. Max Beckmann, who suffered a nervous breakdown in 1915 after serving as a medical orderly, was particularly sensitive to the physical mutilations suffered by veterans, as depicted in his drawing “The Way Home” (1919).

In this third room, visitors can also find the facsimile of the concluding papers of “J’ai tué”, written by Blaise Cendrars and illustrated by Fernand Léger. Cendrars, whose right arm was blown off on the Somme, wrote a book-length poem about the trauma of killing a German soldier. German artist, Conrad Felixmüller, who had refused the draft and so spent four weeks in a mental hospital, drew from personal experience “Soldier in a Madhouse, 2” in 1918. German artist, John Heartfield, né Helmut Herzfeld, commemorated the twentieth anniversary of the war with “Nach Zwanzig Jahren!” (“Twenty Years Later!”) This grim photomontage shows General Paul von Hindenburg standing in front of nine skeletons, next to a procession of marching uniformed and armed boys.

In a little alcove, just off from this third room, at the very end of the exhibition, is a small area for watching film clips. These film clips, which offer a less avant-garde and more mainstream response, are also an important part of the war’s enduring legacy. They include “J’accuse” (1919) and the American war film of the same year, “The Lost Battalion.”

Accompanying the exhibition is a volume of collected essays under the title of “Nothing but the Clouds Unchanged. Artists in World War I.” Quoting from Walter Benjamin’s famous assessment of the war, which evaluated the war as the death knell of the old world and birth of a new order, the book, very much like the exhibition, centers on the artistic responses of tiny, fragile artists. These artists were caught, still borrowing from the words of Benjamin, “in the force field of destructive currents and explosions.” Artists, who didn’t figure in the exhibition, but do in this book, include Robert Graves, Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash, Carlo Carrà, and Oskar Kokoschka. An appendix, “Selected Cultural Figures Who Served in World War I,” covers nineteen warring states and informs the reader of 182 artists, factoring in whether they were killed or wounded and in which theater(s) of war they fought. This appendix contributes fittingly to the Getty’s truly global approach to commemorating the centenary.

Click here for more information on the exhibition, ‘World War I: War of Images, Images of War’

© Centenary Digital Ltd & Author

Image courtesy of The Getty Institute