March 27th marked the centenary of the little-known ‘Battle of the Craters’, which raged two miles south of the Flanders village of St Eloi for three weeks in 1916. CN contributor Matt Warner tells the story.

This desperate battle has been largely forgotten, but it is a clash that deserves closer attention. The use of mines to destroy the German front line would be repeated at Passchendaele, the ‘Tin hat’ was first issued during this battle, and the conditions and weather were appalling. The troops fought ferociously for useless water-filled craters. The 2nd Canadian division would face a bloody baptism of fire, and the battle’s disastrous conclusion would leave the senior officers blaming each other.

Sir Herbert Plumer, the British General commanding the 2nd Army, did not like salients. South of St Eloi the Germans had succeeded in creating a dent 100 yards deep and 600 yards wide. At 4.15 am on March 27th Plumer got his straight line back, temporarily at least. Six huge mines were detonated; the explosion was heard in the Channel port of Folkestone.

British infantry charged into this newly formed landscape, the German defenders either dead or totally disorientated. The plan called for these experienced troops to be relieved by the fresh soldiers of the Canadian 2nd Division once the British 3rd Division had established a new defensible position. This plan was to unravel in the face of determined resistance and increasing confusion.

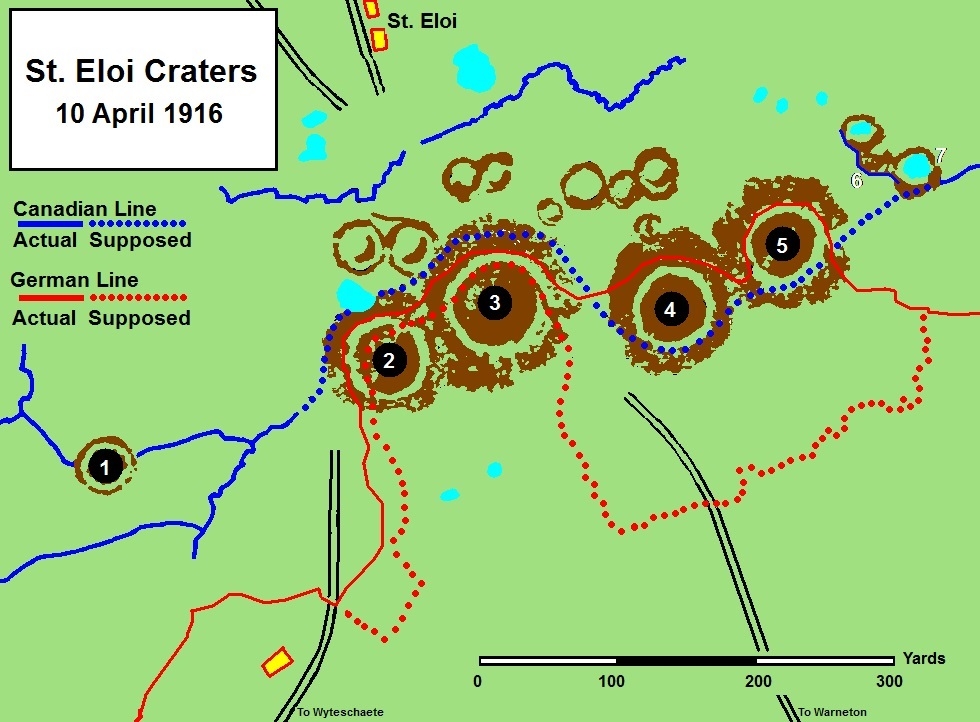

The hardened British troops, who knew the sector and had rehearsed the attack, seized craters 1, 2 and 3 in the west and the smaller crater 6 and an old crater numbered 7 in the east, yet immediately confusion set in. In the centre, craters 4 and 5 were not taken. The Germans, who responded with alacrity, chose to hold C5. Given the crater was about 80 yards wide and 15 yards deep, it was certainly a large hole in the ground but not a large space. However, it required a whole British battalion to take it, which finally seized it back on April 3rd.

(Image courtesy of canadiansoldiers.com)

(Image courtesy of canadiansoldiers.com)

General Plumer decided to relieve the 3rd Division early due to heavy casualties. The 2nd Canadian Division, led by the 31st and 27th Battalions, were to take over by April 4th. As they moved up to the craters by night, they were appalled by what they found. There was no ‘line’ to take over.

Battalion commanders had been told to use wire and MG posts to defend the trenches beyond the craters, but these were largely collapsed. They were horribly exposed to the Germans to the south. Instead of 12 MG posts in their part of the line, the 27th Battalion found there were just 4 Lewis guns to hold craters 4 and 5. Canadian Pioneers worked through the night to cut a new communication trench and shore up the defences, but dawn brought with it a storm of German shells. Much of the work was quickly destroyed. After a bad start, things would get much worse.

The German gunners had a huge advantage in artillery and only a narrow front to aim at. At the bombardment’s height, hundreds of shells and mortar rounds were arriving each minute. Improvised cover and the new steel helmets provided scant protection. Communication between units became impossible. A gap between C3 and C4 was attacked by the Germans at 3.30am on April 6th. Seeing that the 29th Battalion was relieving the 27th along the only communication trench, they had struck at a vulnerable moment. The Canadians were driven backwards. In just three hours the Germans had recaptured all the ground they’d lost on March 27th.

Repulsed

It is at this point that General Sir Richard Turner’s lack of ‘grip’ becomes clear. Unaware of the true disaster HQ reported a ‘suspicion’ that the Germans were in C3 and C4, so an attack was ordered. The 27th and 29th Battalions assaulted but were bloodily repulsed. Meanwhile, men of the 31st advanced on C4 and C5. Completely lost, they actually occupied C6 and C7, where they got cut off. In the featureless terrain, one crater looked much like another. Thirty-three mines had been detonated in this small sector.

Another attack was ordered on C4, but the soldiers got lost again, occupying two smaller craters to the north of their objective; however, they reported that they had secured C4. Newly taken German PoWs contradicted this, saying they held all the central craters. Divisional HQ ignored this disturbing information.

On April 8th Turner told Plumer that perhaps they should give up the craters and let the Germans occupy them so the allied artillery could target them. This shows he did not realise that he didn’t hold the craters, nor did he seem to understand that he had limited guns, as weapons and ammunition were being transferred to the Somme. The Germans weren’t even fired on by what allied guns there were, as the craters they were occupying were thought to be in Canadian hands. Plumer insisted the fighting continue.

Called off

Incredibly Turner did not discover the true situation till April 16th, when Major Ross of the 28th Battalion discovered to his horror that the Germans were in possession of all the craters, bar C6 and C7. A break in the weather allowed a plane to confirm this. Turner finally called off the battle. This was of no help to the 100 men defending C6 and C7. Their position had been targeted by 150 mm shells, striking at the rate of four per minute. Only 11 of them returned to allied lines, with just one uninjured. By the end of the Battle of the Craters, 900 Germans, 1,000 British and 1,347 Canadians had been killed or wounded. All sides ended up where they started.

Turner should have been fired, as his Corp Commander Alderson wanted. He should have sent staff forward to ascertain what was happening. This he never did. However, he was a Canadian hero with a VC, and Haig, stepping in, moved the British General, Alderson, sideways into an inspectorate role, keen to avoid political problems with Canada during the build-up to the Somme. A General he knew to be incompetent was kept in place. Plumer avoided any censure.

All the troops involved fought with great courage, but the Canadians in their first action deserve special praise. They did all they could in a dreadful tactical situation, and paid dearly for prosecuting a hopelessly flawed plan.

© Centenary News & Author

Images: St Eloi Craters battlefield – courtesy of Canadian War Museum/George Metcalf Archival Collection CWM 20020045-2465; St Eloi battlefield diagram – courtesy of canadiansoldiers.com

Further reading

http://www.canadiansoldiers.com/history/campaigns/westernfront/trenchwarfare.htm

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-st-eloi-craters/

https://legionmagazine.com/en/2004/11/slaughter-at-st-eloi/

http://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1049&context=cmh

http://21stbattalion.ca/tributeac/brownlee_wf.html

http://cefresearch.ca/matrix/Nicholson/Transcription/Chapter5.pdf