Collector Andy Moreton has been delving into his prized copy of ‘France at War’ – a book of reports from the front written in 1915 by the British author, poet and journalist Rudyard Kipling, shortly before his own son was killed at the Battle of Loos.

It’s the summer of 1915 and Rudyard Kipling is with allied troops in France, approaching what had once been a bustling town. Now, though, there is no life to be seen:

‘The stillness was as terrible as the spread of the quick busy weeds between the paving-stones; the air smelt of pounded mortar and crushed stone; the sound of a footfall echoed like the drop of a pebble in a well.’

Kipling, the celebrated novelist and Nobel prize-winner, has donned his old journalistic hat and is painting grim pictures of the Great War for readers of the Daily Telegraph in England and the Sun in New York. He’s appalled to see that the town’s cathedral (‘always a favourite mark for the heathen’) has been ripped at the sides and holed in the roof. Then he thinks he hears singing:

“‘Nonsense'”, said an officer. “Who should be singing here?” … But there was singing after all – on the other side of a little door in the flank of the cathedral. We looked in, doubting, and saw at least a hundred folk, mostly women, who knelt before the altar of an unwrecked chapel. We withdrew quietly from that holy ground, and it was not only the eyes of the French officers that filled with tears.’

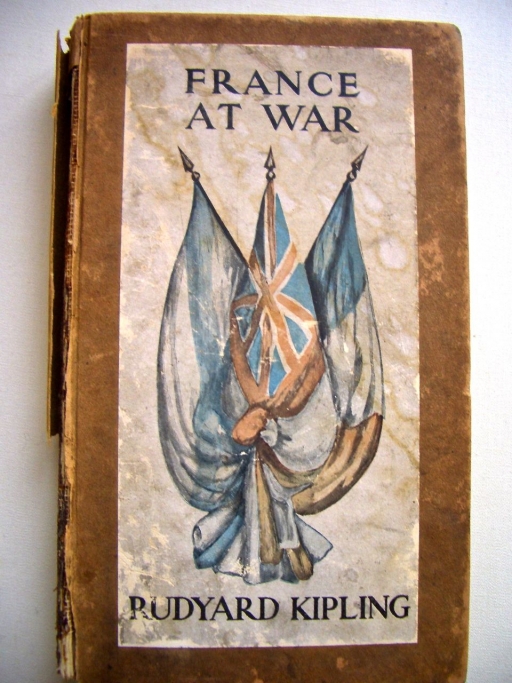

These moving eye-witness vignettes were collected together in a delightful little book called France At War, which was published later in 1915. I prize my copy greatly.

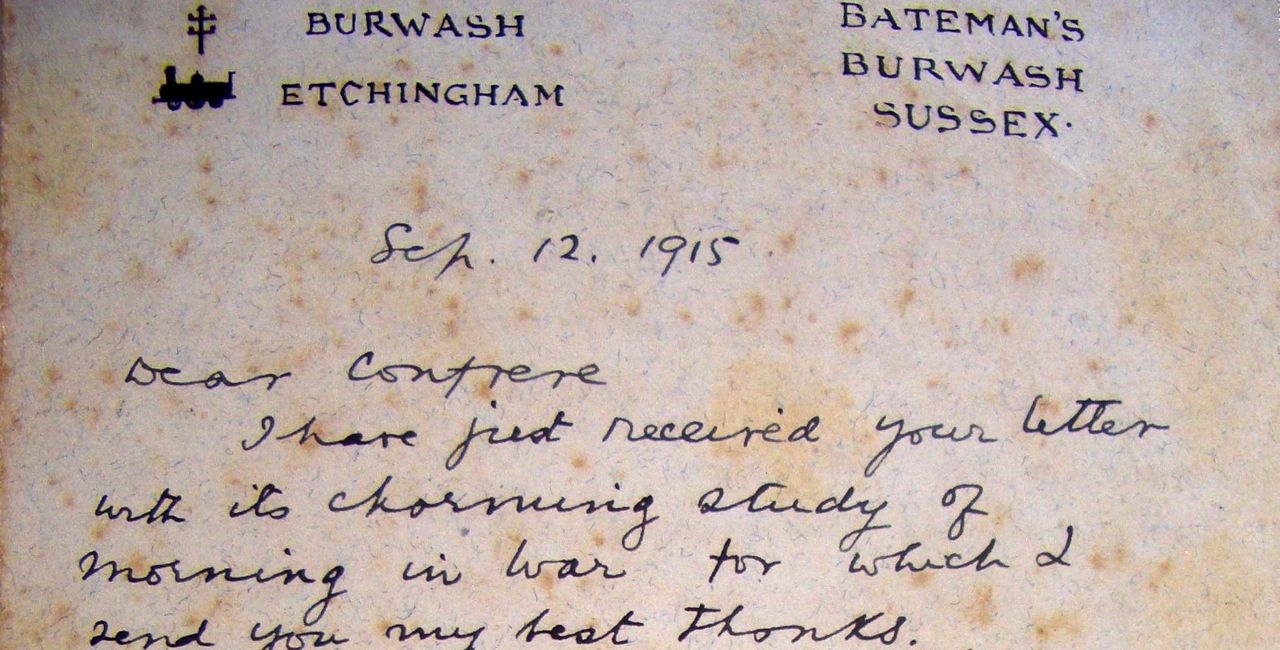

My interest in this side of Kipling’s career stemmed from my passion for collecting celebrity autograph letters. In 2007, I was fortunate enough to obtain a Kipling letter (pictured,below) that I had been stalking for some time. It was written in September 1915, shortly after he’d returned from that assignment in France, and was to someone he simply called ‘confrere’:

I have just received your letter with its charming study of morning in war for which I send you my best thanks. The lines I like best are those which describe the wood as a woman who wakes smiling from sleep – before the rifles begin and all Nature is horrified at the return of daylight and the fighting.

I am sorry indeed to learn that you are in hospital for the second time. There is a rude saying in England, which I venture to present to you for your consolation.

It runs: “Twice wounded,

Safe till you are hanged.”

I do not dare to expand it in French, but it implies that he who is twice wounded is ever after immune against all forms of violent death – except at the hands of justice! This at least gives the soldier a reasonable delay.

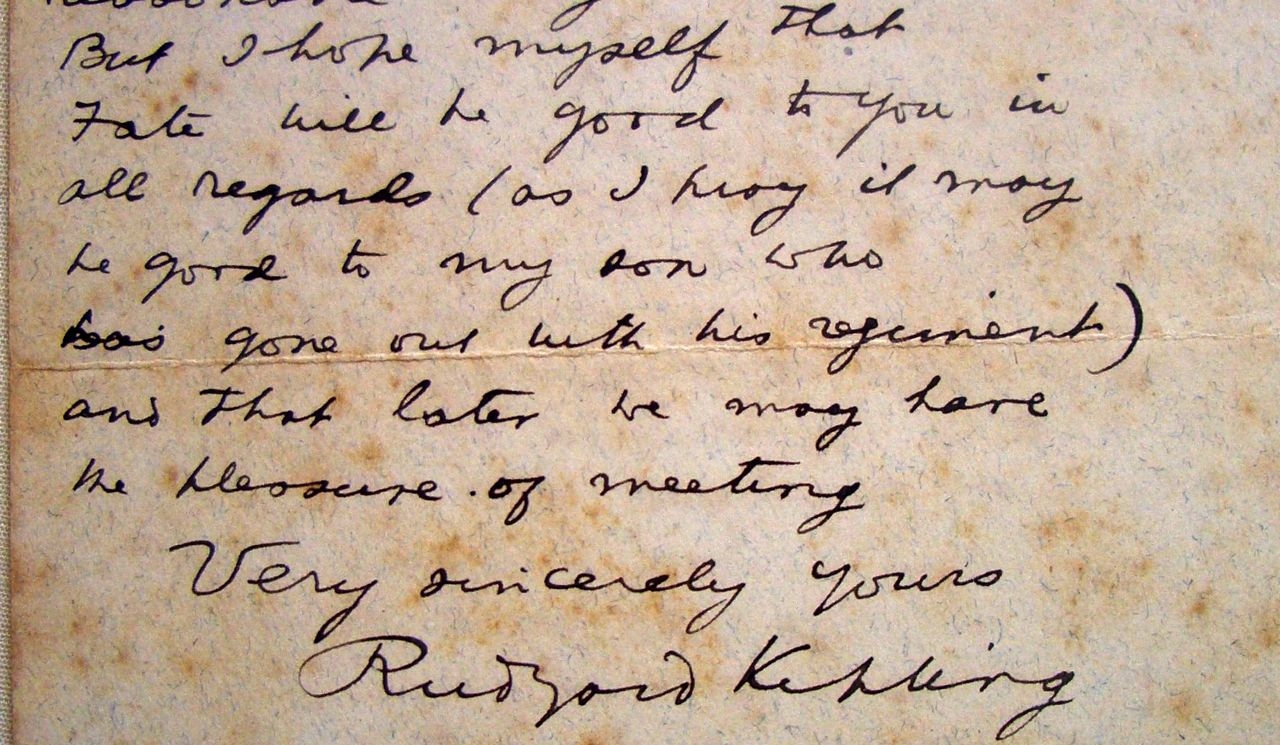

But I hope myself that Fate will be good to you in all regards (as I pray it may be good to my son who has gone out with his regiment) and that later we may have the pleasure of meeting.

Very sincerely yours,

Rudyard Kipling

Of course, the last few words of his letter have a poignancy of their own: just two weeks later, John Kipling was reported ‘wounded and missing’ at the Battle of Loos and later confirmed dead at the age of 18.

Of course, the last few words of his letter have a poignancy of their own: just two weeks later, John Kipling was reported ‘wounded and missing’ at the Battle of Loos and later confirmed dead at the age of 18.

My research led me to conclude that Kipling’s confrere was Abel Moreau (1893–1977), who survived the First World War to become a celebrated journalist and novelist (La Lumière des hommes, 1943; Le Front à la Vitre, 1951; Drames de Gosses, 1955). There’s no knowing the link between the two men (they clearly hadn’t met), but it may be that Kipling came across Moreau’s parents while in France, and they shared the common bond of having a young son at the Front.

Some time after the war, Kipling began a correspondence with another French soldier, Maurice Hammoneau, who had an extraordinary tale to tell. After an artillery attack near Verdun, Hammoneau lay wounded and unconscious for several hours. When he regained his senses, he realised that a 1913 French pocket edition of Kipling’s Kim had deflected a bullet and saved his life.

Hearing that Kipling was mourning the loss of his son, Hammoneau sent him the ravaged book (with the bullet still embedded, some reports say) and his Croix de Guerre. Kipling, deeply moved, said he would return them if Maurice ever had a son. He did, naming him Jean in honour of John Kipling and asking Rudyard to be his godfather. Kipling duly returned the items with a charming letter to young Jean, advising him always to carry a book of at least 350 pages in his left breast pocket.

Much as I can dream, the celebrated book and correspondence are not likely to grace my collection any time soon. They are safely and carefully preserved in the Library of Congress.

© Centenary News & Author

Images © Andy Moreton