New British planes entering service in 1917 earned distinctly mixed reviews from their crews, as CN contributor Matthew Warner explains.

Early 1917 saw the introduction of three very different aircraft into Royal Flying Corps (RFC) service. Each was a two-seater designed for reconnaissance and light bombing: the superb Bristol F2b, the fine, yet flawed, Airco DH4 and the appalling Royal Aircraft Factory RE8. They showed not only the contrasting aeronautical concepts of the time but also the capricious nature of war. The type that the aircrew were sent to operate often determined their fate. My grandfather, Douglas Gould, who was an Observer in the RFC, adored the F2b, disliked the DH4 and pitied those in the RE8.

As the Battle of the Somme raged through 1916, the obvious obsolescence of the RFC’s mainstay two-seater, the BE2c, couldn’t be ignored any longer. This plane lacked speed, maneouverablilty, ceiling, climb rate and firepower. German fighters found the BE2c easy prey.

The first versions of the RE8 (which stood for Reconnaissance Experimental) began to arrive at the end of 1916 in small numbers. The initial excitement of the BE2c crews quickly turned to disgust and then to requests to have their old planes back; that’s how bad the RE8 was.

Royal Aircraft Factory RE8

RE8 aircraft number E1114 during the First World War (Photo IWM © Q 80682)

RE8 aircraft number E1114 during the First World War (Photo IWM © Q 80682)

This aircraft was designed by the Royal Aircraft Factory. This was something of a misnomer, as it built few planes; rather it was a design bureau with a strong concept of what warplanes were for and therefore how they should be built. It was led by the powerful and influential Superintendent, Sir Mervyn O’Gorman, who brought scientific rigour to the organisation and was a popular man with his designers. He had the same mind-set of the senior officers in the RFC when it came to the role of planes; i.e. a kind of airborne cavalry used to gather information, so reconnaissance was the primary concern. The large plate-glass cameras of the time required a stable platform and that was what was going to be provided. Any other consideration such as survivability in the combat area was secondary.

Problems

As a result the RE8 was a good, stable platform for taking photos. That was about its only positive. When 52 Squadron received the plane late in 1916 it soon discovered severe problems. The small tailplane broke off during hard manoeuvres, or a spin developed, both fatal. This was dealt with by a hurried re-design. The other problems proved insoluble. The radiator and intake completely blocked the pilot’s forward view, making landing hard. Exacerbating this was the centre of gravity, which was too far to the rear. A rough landing would result in the RE8 tipping onto its nose, forcing the engine into the fuel tank, which would then ignite.

Worst of all were the stall characteristics. The plane didn’t ‘talk’ to the pilot, making it difficult for novice pilots to fly. The official stall speed was 47mph; however, as the CO of 34 Sqn explained in his detailed pilot notes, low airspeed could be deadly. ‘Remember, the machine gives little indication of losing its speed until it shows an uncontrollable tendency to dive, which cannot be corrected in time…avoid gliding too slowly, at 65mph when gliding the machine suddenly loses speed…just the extra resistance of the rudder is sufficient to bring down the pace.’

The accident rate was so high it was decided that only experienced aircrew should fly the type. This ugly plane was slow, with a top speed of 103mph, and losses in combat were high. However, by March 1917 the RE8 was being delivered in greater numbers.

Airco DH4

Airco DH4 Westland built c1919 (Photo © IWM Q 105405)

Introduced to squadrons in January 1917, the Airco DH4 was very different. Designed by Geoffrey de Havilland to have the performance to get to and from targets unescorted it was in some ways a forerunner of his much later Mosquito. With an unmatched top speed of 144mph, this capable plane had many admirers. My grandfather wasn’t one of them: ‘You couldn’t talk to the pilot. You were on your own,’ he remembered. The long range of the DH4 was in part due to the large fuel tank sitting between the crew. Psychologically this wasn’t ideal but, worse, it put the observer out of reach from the front seat. The crew lost that vital ability to work as a team, unable to point out to each other either threats or opportunities.

However, while my grandfather disliked the DH4, pilots enjoyed its sparkling performance. If things looked bad, the DH4 pilot could open the throttle and out-run any German fighter using its reliable and very powerful Rolls Royce Eagle.

Over 6,000 DH4s were built, with only 1,800 constructed in Britain, the rest in the US. The ‘Liberty Biplane’ as they called it was hugely popular with the Americans. The Medal of Honor was awarded to six airmen during the Great War, of which four were flying in a DH4.

Bristol F2b

The best two-seat plane of the war got off to the worst start. On 5 April 1917 six Bristol F2s set out on a reconnaissance mission. Attacked by six Albatros DIIIs from Manfred von Richthofen’s unit, four were destroyed. Witnesses on the ground said that the British stuck in formation and made no attempt to use their forward firing Vickers machine guns. Led by Leefe Robinson VC, the crews were veterans but used to the BE2c. They stayed in formation, as that was how one hoped to survive in that type. It seems incredible but none of them seem to have realised they now had a fighter that could match any single-seater the Germans had. Not even the name official name ‘Bristol Fighter’ seems to have tipped them off.

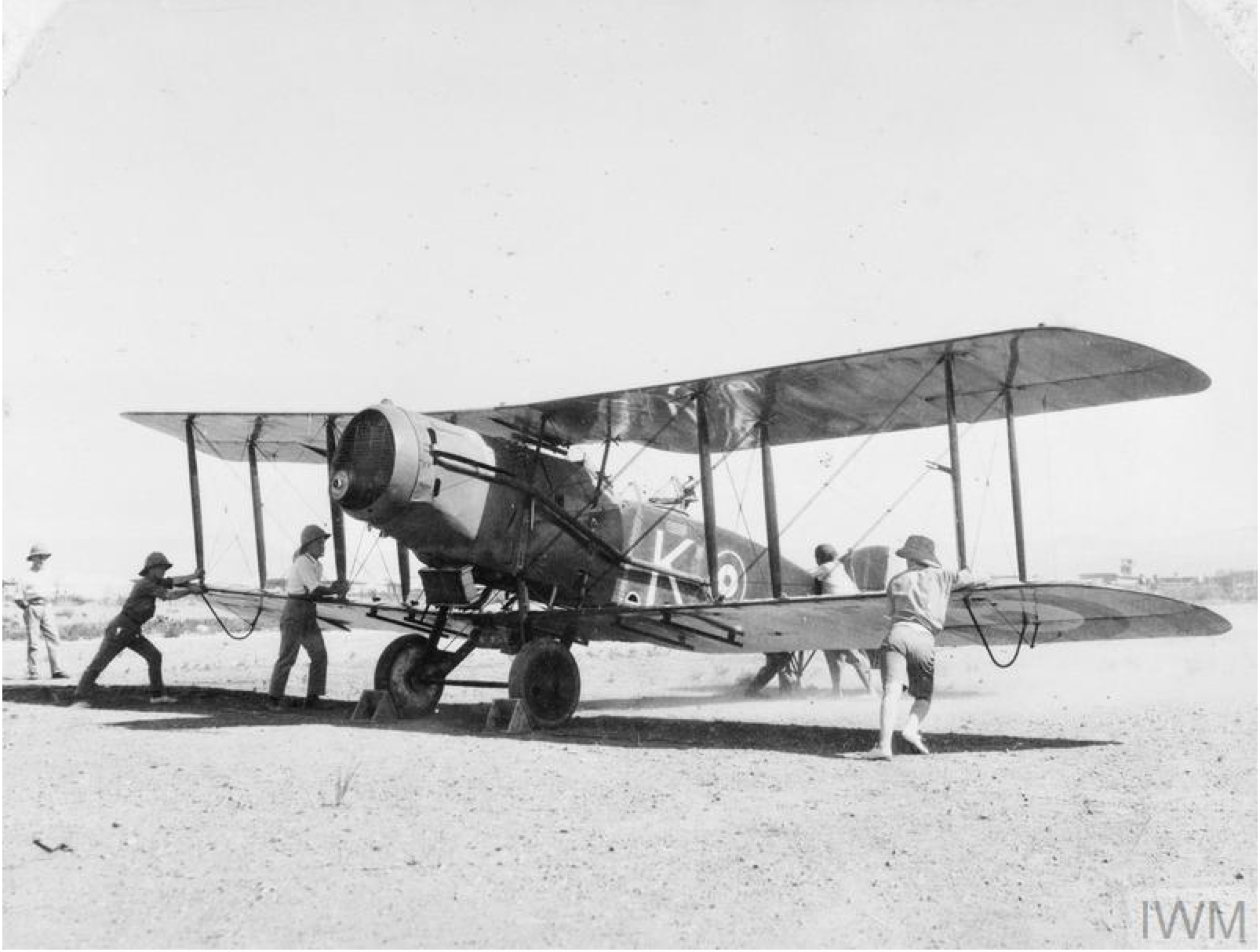

Running up the engine of Bristol F2b Mark II, J6647 ‘K’, of No. 31 Squadron at Dardoni, before taking off on a bombing sortie — North Waziristan, 1923 (Photo © IWM HU 89355)

The F2b was designed by aviation pioneer Frank Barnwell, who, uniquely amongst designers, had front-line experience. He flew with 12 Squadron, flying the BE2c until 1915. He knew what a fighter pilot wanted so set out to build an aircraft that could out-perform opponents. For example the odd arrangement of having the fuselage set between the wings wasn’t for aerodynamics but to give the pilot an excellent view and the gunner a much better field of fire. Agile and fast with an excellent Rolls Royce Falcon engine, the F2b could carry out reconnaissance missions unescorted .The crew sat back-to-back, making communication and teamwork easy. This plane had more aces than any other two-seater, the top scorer being Canadian Andrew McKeever who shot down 31 enemy planes, while his observer Leslie Powell destroyed 19. The Germans developed a healthy respect for the F2b and avoided it when possible. A total of 3,101 were built during the First World War.

Nicknames

An examination of the nicknames given to these machines tells much. The RE8 became the ‘Harry Tate’, a popular comic of the time. It must have been in part down to the comically bad performance, the black humour of aircrew and the rhyme. The DH4 had a very unfortunate moniker – ‘The Flaming Coffin.’This is unfair, as it was no more likely to burn than any other type, but shows the psychological flaws in the position of the fuel tank. The F2b was known as the pugilistic-sounding ‘Biff’, in keeping with its fighter pedigree.

Post-war F2bs found many roles but most remarkable was its RAF service, which lasted until 1932, just three years before the Hurricane first flew. The DH4 found a multitude of uses after the war as the nascent airline industry adopted it, valuing the speed and range. Thousands kept flying into the 1930s. And of the 4,077 RE8s manufactured? All were withdrawn from military service in 1918 and not a single aircraft was registered for civilian use.

© Centenary News & Matthew Warner

Images courtesy of Imperial War Museums © IWM Q 80682 (RE8); © IWM Q 105405 (DH4); © IWM HU 89355 (from the Service of Air Vice-Marshal Gerard Combe in the Royal Air Force 1923-1946); Matthew Warner (Douglas Gould archive)

Posted by: CN Editorial Team